Overview

Ours is a world of water. The oceans cover seven tenths of the Earth's surface. They regulate global climate, function as reservoirs of heat and carbon, even provide us with most of the oxygen we breathe. But it was only with the coming of the satellite age that we gained an accurate global view of the seas that surround us.

Transporting energy across the globe

The oceans absorb and store heat much more effectively than land or ice surfaces, and work like heat engines within our climate system. They take in half of all inbound solar energy at the equator and transport it along in currents towards the poles.

Europeans have the Gulf Stream to thank for saving them from Arctic-style winters, while the recurrent Tropical Pacific El Niño oscillations not only dramatically alters regional weather patterns in Asia and the Americas but has a wider global impact.

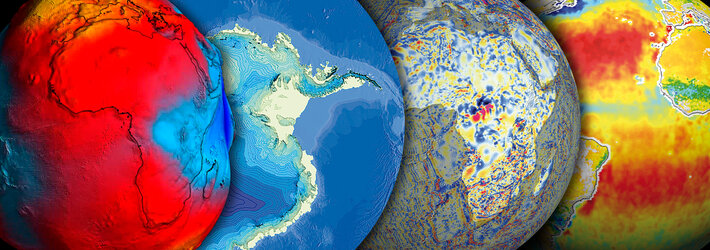

Measuring sea surface temperature from space to an accuracy of a fraction of a degree – using such instruments as the AATSR (Advanced Along Track Scanning Radiometer) aboard ESA's Envisat – is the most accurate means of discerning the extent of global warming.

Ocean current circulation can be tracked too, because their temperature differs from the waters around them. And as zones of warmer water stand a few centimetres higher in the ocean, Radar Altimeter measurements of sea surface height can also map currents to a high level of precision.

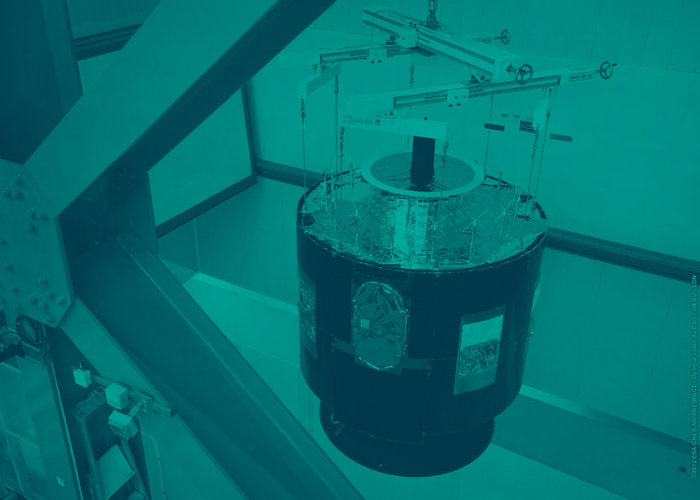

Heat energy drives water away from the equator, but salt drives them back again. Deepwater currents return cold waters back from the poles, sinking beneath warmer water due to their lower salinity. ESA's Soil Moisture and Ocean Salinity (SMOS) mission is set to measure ocean salinity for the first time to discover if global warming is altering this vital mechanism.

Phytoplankton – the grass of the sea

The sea was the first place life on Earth thrived – and it thrives there still. Microscopic marine phytoplankton floating in the top hundred metres of ocean waters are individually insignificant but are collectively the most influential organisms on Earth.

As 'primary producers' they form the base of the marine food chain, while up on land we could not live without them: despite forming less than 1% of global biomass phytoplankton perform half of all photosynthesis, breathing out oxygen into the atmosphere. They also absorb a large amount of the surplus carbon dioxide generated by human activity, mitigating the greenhouse effect.

Despite their tiny size, they can be observed from space: as well as tracking pollution and oil slicks, the MERIS spectrometer on Envisat was set to monitor global phytoplankton distribution by detecting chlorophyll pigments in seawater. By knowing their numbers more precisely researchers can improve the accuracy of climate change models.

Wind and waves

The sea surface is ever changing, but space-based radar scatterometers provide us with global maps of wind speed and wave height for the first time. Besides increasing safety at sea – 90% of world trade crosses the oceans - more than a decade of data from ERS scatterometers can be used to investigate the possibility that maximum wave heights are increasing due to global warming.

The future

The oceans are where our future will be determined. As the planet's reservoirs of heat, oceanic cold deep waters also have dissolved within them most of the planet's carbon. If increasing temperature causes them to release this carbon, then the process of global warming will be greatly hastened.

And as the world warms, so sea level has been increasing, a fact confirmed by satellite altimeter data for the last ten years. An accelerated sea level rise coupled with melting of polar ice could change the very face of our planet – but continued satellite monitoring will give us early warning of things to come.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland