Volcanoes

There are about 1,500 active volcanoes on the Earth's surface - the majority following along the Pacific 'Ring of Fire' – and around 50 of these erupt each year. At least 500 million people live close to an active volcano. Space-based monitoring helps identify those volcanoes presenting greatest danger, and in the aftermath maps the damage done.

Mass evacuation

In January 2002 up to half a million people had to flee their homes along the slopes of Mount Nyiragongo in eastern Congo. Scorching lava overwhelmed 14 villages and reaching the regional capital Goma. The sky was darkened by sulphurous clouds of volcanic dust and steam. At least 50 people were killed during the eruption.

As world population increases, so does the potential threat from every eruption. But there is no way ground-based monitoring can be carried out of all volcanoes across the globe. Many volcanic peaks are inaccessible or sometimes too dangerous to be approached.

Early warning from space

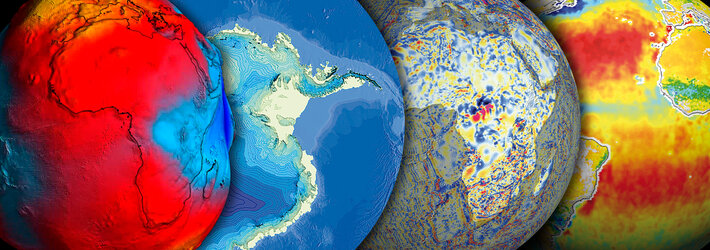

But continuously-gathered satellite data can be used to assess risk, and detect the slight signs of change that may foretell an eruption. In Italy, ERS data has been used to study the ancient but extremely active Mount Etna over the course of a decade.

Radar interferometry shows sub-centimetre-scale movement of Etna's slopes as the volcano's underground magma chamber fills, and builds up pressure for a future eruption. A time-lapse animation of interferometry data shows a volcano that appears to be breathing.

Reviving 'dead' volcanoes

The same technique is being applied to volcanoes worldwide. California Institute of Technology researchers used radar interferometry data to survey 900 volcanoes in the Central Andes. They found movement of between one and two centimetres a year on the slopes of four volcanoes previously classed as inactive, located in Bolivia, Argentina and Peru.

When an eruption begins, optical and radar instruments can image the various phenomena associated with it, including lava flows, mud slides, ground fissures and earthquakes. Atmospheric sensors can identify the gases and aerosols released by the eruption, and quantify their wider environmental impact.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland