Galileo to spearhead extension of worldwide search and rescue service

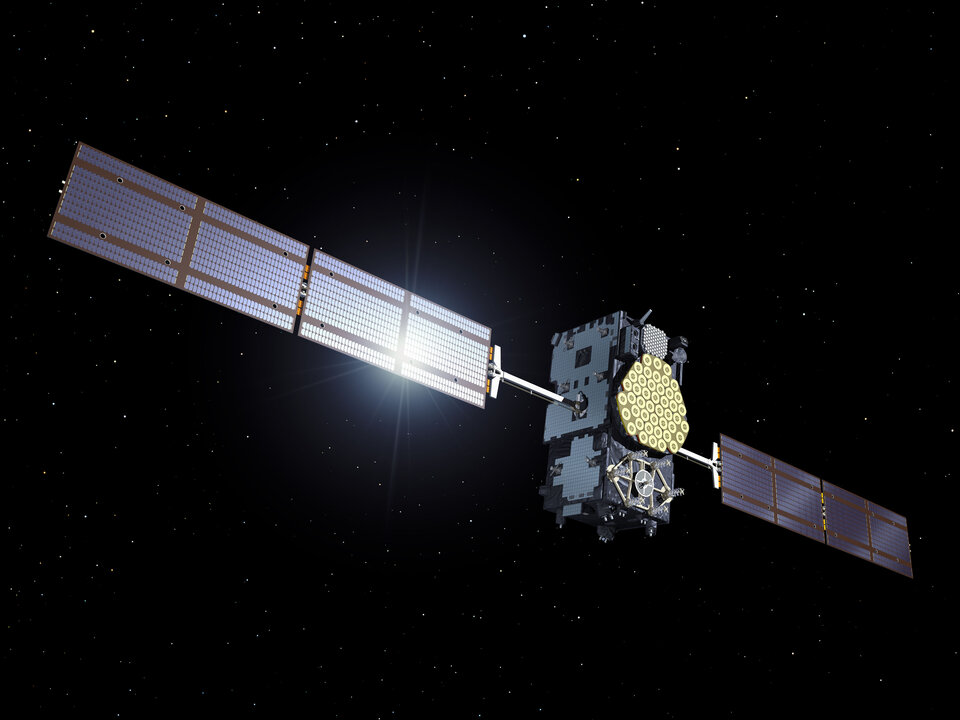

The global reach of Europe’s Galileo navigation system is being harnessed to pinpoint distress calls for rapid search and rescue. A major expansion of the humanitarian system will be tested over the next two years to make it even more effective.

After rowing the Atlantic for 27 days, the six-man Atlantic Odyssey Sara G team suddenly capsized. The morning of 30 January saw them 800 km from land, clinging to their lifeboat in rough seas – but their distress call was detected from orbit. Rescue came within 14 hours.

The international Cospas–Sarsat satellite relay system has been making air and sea travel safer for 30 years, saving 24 000 lives along the way.

Cospas is a Russian acronym for ‘Space System for the Search of Vessels in Distress’, with Sarsat standing for ‘Search and Rescue Satellite-Aided Tracking’.

Satellites locate the source of distress calls from radio beacons on ships and aircraft, then local authorities are alerted.

“The service’s slogan is ‘taking the search out of search and rescue’,” explained ESA engineer Igor Stojkovic.

He participated in a week-long Cospas–Sarsat task group meeting from 27 February hosted at ESA’s ESTEC technical centre in Noordwijk, the Netherlands, with representatives from 21 nations, plus the European Commission and ESA for Galileo.

“We’ve finalised plans for a worldwide test campaign as we extend existing Cospas–Sarsat capabilities to international navigation satellites,” added Igor.

“Search and rescue packages are also being carried by US GPS and Russian Glonass satellites, though with most of Europe’s Galileo constellation being deployed within the next few years, Galileo is leading the way.”

Founded by Canada, France, Russia and the US, Cospas–Sarsat began with ‘transponders’ on low-orbit satellites.

“Their rapid orbital motion means that Doppler ranging can be performed to pinpoint the location of distress calls,” said Igor.

“However, only a small area of Earth is covered at a time, and it may take valuable time to line up with a ground station to relay a message – and it takes two satellite passes to pinpoint the distress call.”

In the 1990s Cospas–Sarsat introduced coverage from geostationary orbit, looking down from almost 36 000 km.

With these satellites remaining in a fixed point in the sky, distress calls are detected and relayed immediately, although their relative lack of motion means Doppler-based ranging is not possible.

“Now Cospas–Sarsat is moving to using navigation satellites in medium orbits,” added Igor.

“Navigation satellite constellations have been carefully designed for worldwide coverage, and can perform a combination of time- and frequency-based ranging for single-burst distress call positioning.”

The first medium-orbit transponder was launched on a Glonass satellite last year, with two more flying aboard Galileo satellites due for launch at the end of summer.

“These satellites will be the focus of our demonstration and evaluation phase, the results of which will set working standards for the operational system to follow from 2015,” said Igor.

Galileo engineers have introduced another innovation: for the first time those in distress will receive a reply, letting them know their signal was picked up and help is on the way.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland