Accept all cookies Accept only essential cookies See our Cookie Notice

About ESA

The European Space Agency (ESA) is Europe’s gateway to space. Its mission is to shape the development of Europe’s space capability and ensure that investment in space continues to deliver benefits to the citizens of Europe and the world.

Highlights

ESA - United space in Europe

This is ESA ESA facts Member States & Cooperating States Funding Director General Top management For Member State Delegations European vision European Space Policy ESA & EU Space Councils Responsibility & Sustainability Annual Report Calendar of meetings Corporate newsEstablishments & sites

ESA Headquarters ESA ESTEC ESA ESOC ESA ESRIN ESA EAC ESA ESAC Europe's Spaceport ESA ESEC ESA ECSAT Brussels Office Washington OfficeWorking with ESA

Business with ESA ESA Commercialisation Gateway Law at ESA Careers Cyber resilience at ESA IT at ESA Newsroom Partnerships Merchandising Licence Education Open Space Innovation Platform Integrity and Reporting Administrative Tribunal Health and SafetyMore about ESA

History ESA Historical Archives Exhibitions Publications Art & Culture ESA Merchandise Kids Diversity ESA Brand CentreLatest

Space in Member States

Find out more about space activities in our 23 Member States, and understand how ESA works together with their national agencies, institutions and organisations.

Science & Exploration

Exploring our Solar System and unlocking the secrets of the Universe

Go to topicAstronauts

Missions

Juice Euclid Webb Solar Orbiter BepiColombo Gaia ExoMars Cheops Exoplanet missions More missionsActivities

International Space Station Orion service module Gateway Concordia Caves & Pangaea BenefitsLatest

Space Safety

Protecting life and infrastructure on Earth and in orbit

Go to topicAsteroids

Asteroids and Planetary Defence Asteroid danger explained Flyeye telescope: asteroid detection Hera mission: asteroid deflection Near-Earth Object Coordination CentreSpace junk

About space debris Space debris by the numbers Space Environment Report In space refuelling, refurbishing and removingSafety from space

Clean Space ecodesign Zero Debris Technologies Space for Earth Supporting Sustainable DevelopmentSpace weather

Space weather and its hazards ESA Vigil: providing solar warning ESA Space Weather Service NetworkLatest

Applications

Using space to benefit citizens and meet future challenges on Earth

Go to topicObserving the Earth

Observing the Earth Future EO Copernicus Meteorology Space for our climate Satellite missionsCommercialisation

ESA Commercialisation Gateway Open Space Innovation Platform Business Incubation ESA Space SolutionsLatest

Enabling & Support

Making space accessible and developing the technologies for the future

Go to topicBuilding missions

Space Engineering and Technology Test centre Laboratories Concurrent Design Facility Preparing for the future Shaping the Future Discovery and Preparation Advanced Concepts TeamSpace transportation

Space Transportation Ariane Vega Space Rider Future space transportation Boost! Europe's Spaceport Launches from Europe's Spaceport from 2012Latest

Didymos and Dimorphos

Thank you for liking

You have already liked this page, you can only like it once!

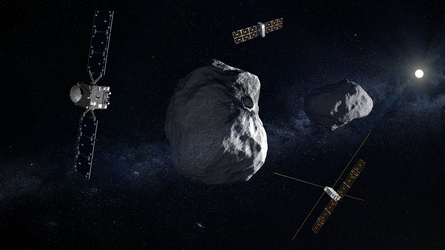

With its Hera mission, ESA is visiting the double asteroid Didymos. Around 15% of asteroids are believed to be double (or triple) asteroid systems. Some of these have been discovered through their lightcurves or radar surveys, but parallel discoveries have also been made on the ground, with ‘doublet’ impact craters caused by binary impacts – such as the adjacent Nördlinger Ries and Steinheim craters in Bavaria, Germany – along with others spotted on Mars and Venus.

The formation of asteroid moons has been shown to be a natural outcome of large asteroid disruptions – during which some fragments are ejected and remain bound together. Many of these bodies have a ‘rubble pile’ composition. This has inspired a theory that gradual increases in their rotation due to the warming of sunlight could actually lead to matter being thrown out into space by centrifugal force, some of it remaining bound to the central body and forming into a ‘moon’.

Due to the relatively small masses and gravities of the bodies involved, the smaller asteroids orbit their parents at comparatively low velocity, less than a metre per second. This opened up the possibility that it might be feasible to shift the orbit of one of these asteroid moons in a measurable way – something which would not be achievable so precisely with a lone asteroid in a much more rapidly moving solar orbit.

Hera will take advantage of this option to try to find out whether asteroids can be deflected if they pose a risk to Earth.

This artist’s impression is taken from the video Hera: ESA’s Planetary Defence Mission.

-

CREDIT

ESA – Science Office -

LICENCE

ESA Standard Licence

Hera glides past Didymos to Dimorphos

Hera approaching Didymos asteroids

Discover Didymos and Dimorphos – the ancient travell…

Hera networking with CubeSats

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland