Accept all cookies Accept only essential cookies See our Cookie Notice

About ESA

The European Space Agency (ESA) is Europe’s gateway to space. Its mission is to shape the development of Europe’s space capability and ensure that investment in space continues to deliver benefits to the citizens of Europe and the world.

Highlights

ESA - United space in Europe

This is ESA ESA facts Member States & Cooperating States Funding Director General Top management For Member State Delegations European vision European Space Policy ESA & EU Space Councils Responsibility & Sustainability Annual Report Calendar of meetings Corporate newsEstablishments & sites

ESA Headquarters ESA ESTEC ESA ESOC ESA ESRIN ESA EAC ESA ESAC Europe's Spaceport ESA ESEC ESA ECSAT Brussels Office Washington OfficeWorking with ESA

Business with ESA ESA Commercialisation Gateway Law at ESA Careers Cyber resilience at ESA IT at ESA Newsroom Partnerships Merchandising Licence Education Open Space Innovation Platform Integrity and Reporting Administrative Tribunal Health and SafetyMore about ESA

History ESA Historical Archives Exhibitions Publications Art & Culture ESA Merchandise Kids Diversity ESA Brand Centre ESA ChampionsLatest

Space in Member States

Find out more about space activities in our 23 Member States, and understand how ESA works together with their national agencies, institutions and organisations.

Science & Exploration

Exploring our Solar System and unlocking the secrets of the Universe

Go to topicAstronauts

Missions

Juice Euclid Webb Solar Orbiter BepiColombo Gaia ExoMars Cheops Exoplanet missions More missionsActivities

International Space Station Orion service module Gateway Concordia Caves & Pangaea BenefitsLatest

Space Safety

Protecting life and infrastructure on Earth and in orbit

Go to topicAsteroids

Asteroids and Planetary Defence Asteroid danger explained Flyeye telescope: asteroid detection Hera mission: asteroid deflection Near-Earth Object Coordination CentreSpace junk

About space debris Space debris by the numbers Space Environment Report In space refuelling, refurbishing and removingSafety from space

Clean Space ecodesign Zero Debris Technologies Space for Earth Supporting Sustainable DevelopmentLatest

Applications

Using space to benefit citizens and meet future challenges on Earth

Go to topicObserving the Earth

Observing the Earth Future EO Copernicus Meteorology Space for our climate Satellite missionsCommercialisation

ESA Commercialisation Gateway Open Space Innovation Platform Business Incubation ESA Space SolutionsLatest

Enabling & Support

Making space accessible and developing the technologies for the future

Go to topicBuilding missions

Space Engineering and Technology Test centre Laboratories Concurrent Design Facility Preparing for the future Shaping the Future Discovery and Preparation Advanced Concepts TeamSpace transportation

Space Transportation Ariane Vega Space Rider Future space transportation Boost! Europe's Spaceport Launches from Europe's Spaceport from 2012Latest

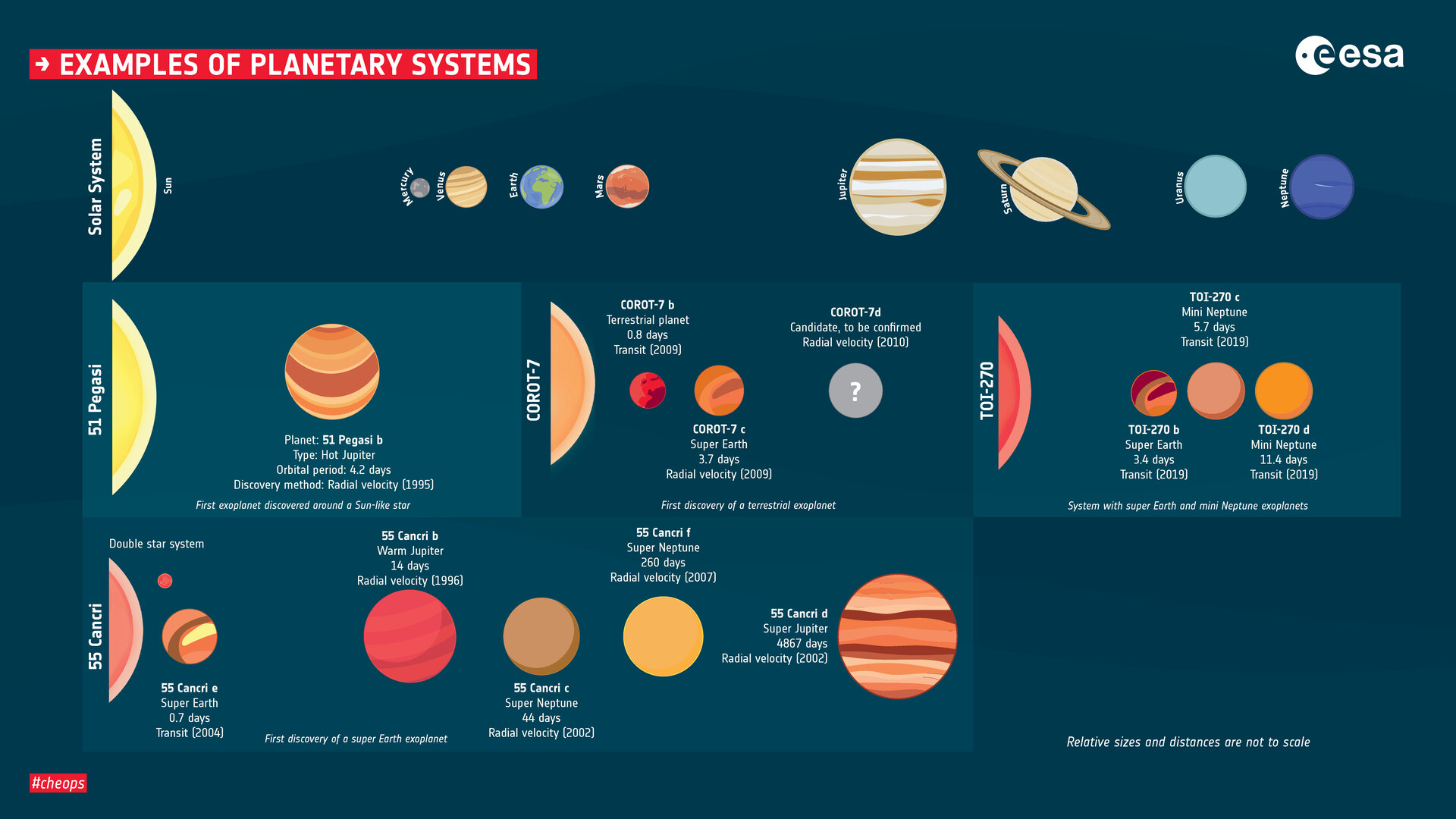

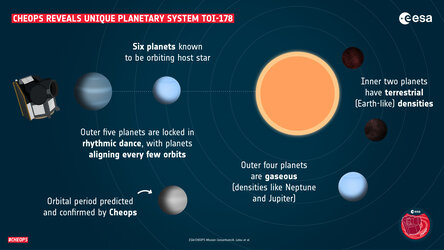

Examples of planetary systems

Thank you for liking

You have already liked this page, you can only like it once!

Examples of different exoplanet systems compared to the Solar System. Relative sizes and distances are not to scale.

The discovery of the first exoplanet around a Sun-like star, 51 Pegasi, was announced in 1995 by Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz of the Geneva Observatory in Switzerland. This detection marked a pivotal moment in the study of exoplanets.

51 Pegasi b – the exoplanet discovered by Mayor and Queloz – is a Jupiter-mass planet that orbits close to its star, which results in a relatively large radial velocity signal. This type of planet, a gas giant orbiting very close to its parent star and known as a hot Jupiter, came as a complete surprise when discovered since theories of planet formation stated that such a planet could not form so close to a star due to the lack of material for it to sweep up. This "impossible planet" was explained in 1996 by Douglas Lin at Lick Observatory, California, and colleagues. They suggested that the gas giant had indeed formed further out, but then migrated towards the star as a result of interactions with the circumstellar disc from which the planet was born.

As of late 2019, more than 4000 exoplanets have been confirmed. Some are massive like Jupiter but orbit much closer to their host star than Mercury does to our Sun, others are rocky or icy, and many simply do not have analogues in our Solar System. There are systems hosting more than one planet, a planet orbiting two stars, and a handful of planets that may even have the right conditions for water to be stable on their surfaces, a necessary ingredient for life as we know it.

Terrestrial exoplanets orbiting close to their star feel the heat – both directly from the star as well as from tidal forces – and it is thought that "lava planets" could result. These are hypothetical planets where the entire surface would be molten rock. CoRoT-7b, discovered by the CNES-led mission CoRoT (Convection, Rotation and planetary Transits) in 2009, is a candidate for this type of planet.

Another oddity is a potential diamond planet. The planets in our Solar System formed in a protoplanetary disc that was rich in silicon and oxygen, but models predict that it is possible that discs around other stars could be rich in carbon instead. Planets in these systems could have layers of graphite or diamonds depending on the pressure within the planet. Diamond planets are still only theoretical, although one possibility is the super-Earth 55 Cancri e, discovered in 2004 around the star 55 Cancri, as it has hints of a carbon-rich atmosphere.

By far the vast majority of exoplanets that have been detected to date are of a size that appears to be absent from our Solar System. Dubbed "super-Earths" or "mini-Neptunes" they have masses between those of Earth and Neptune. Since for most of these exoplanets only the mass or the radius, but not both values, are known, it is not possible to determine if they are small and rocky Earth-like planets or slightly larger gas-enshrouded Neptune-like planets.

An example of a planetary system hosting "super-Earths" and "mini-Neptunes" is that found around the star TOI-270 by NASA's Tess mission in 2019.

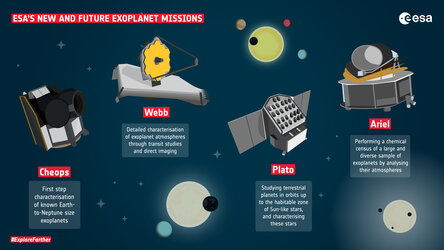

ESA’s Characterising Exoplanet Satellite, Cheops, will characterise several hundreds of these known planets by measuring minuscule brightness changes due to the planet’s transit across the star’s disc.

The mission will target stars hosting planets in the Earth- to Neptune-size range, yielding precise measurements of the planet sizes. This, together with independent information about the planet masses, will allow scientists to determine their density, enabling a first-step characterisation of these extrasolar worlds. A planet’s density provides vital clues about its composition and structure, indicating for example if it is predominantly rocky or gassy, or perhaps harbours significant oceans.

-

CREDIT

ESA -

LICENCE

ESA Standard Licence

Transiting exoplanets

ESA’s new and future exoplanet missions

Cheops

Cheops

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland