Marangoni experiment

Researchers are preparing for a new round of International Space Station experiments in a facility designed to demystify the role of surface tension and instabilities (Marangoni effects) on heat transfer to, and within an evaporating or condensing fluid. The tools: lasers, purple light and an out-of-focus camera to get the sharpest result.

Before any experiment can take place, the scientific tools need to be perfected. For these experiments, the first inserts are set to launch in 2023. The researchers are looking to observe changes on the micron level – smaller than bacteria and viruses.

In December 2011, researchers tested a system in Nivelles, Belgium, shining a laser on a metal fin and using a high-precision interferometer to record changes. During the experiment, the fin is cooled and subsequently covered with a condensing liquid film. The interferometer records the temperature changes and vapour concentration variations around the fin, while the interferometer’s optical mode tracks the liquid film’s thickness with high precision.

“Interestingly we need the optical camera to be slightly out of focus to get the best result,” says ESA Payload System Engineer Ana Frutos Pastor, “by focussing just behind the fins, we can distinguish the contours with microscopic accuracy.”

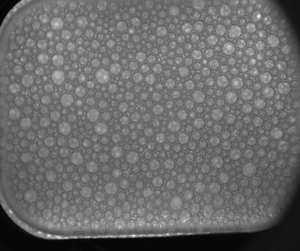

The Marangoni effect describes how particles can be moved along liquids as they interact with changing temperatures. To better understand and control the instability, a second set of experiments will focus on small 20 mm square plaques with minute peaks and valleys, just a few hundred microns high. Flooded with liquid and heated, a technique based on blue and red light that shows as purple will be used to measure down to the micron how the temperature differences at the liquid’s surface lead to the formation of peaks and valleys.

“These experiments mainly serve to confirm or refine mathematical models, this is fundamental physics,” explains Balazs Toth of ESA’s Fluid Science Payloads Team, “but the effects they are studying play on many things around us, from how a coffee stain evaporates to how computers are cooled as you read this sentence, and how life support systems of spacecraft could be improved.”

The first hardware models were built by QinetiQ Space in Kruibeke, Belgium, and have been tested by the science teams. These models contain all of the fluid and thermal management systems as well as the shiny new diagnostic methods, of course.