Accept all cookies Accept only essential cookies See our Cookie Notice

About ESA

The European Space Agency (ESA) is Europe’s gateway to space. Its mission is to shape the development of Europe’s space capability and ensure that investment in space continues to deliver benefits to the citizens of Europe and the world.

Highlights

ESA - United space in Europe

This is ESA ESA facts Member States & Cooperating States Funding Director General Top management For Member State Delegations European vision European Space Policy ESA & EU Space Councils Responsibility & Sustainability Annual Report Calendar of meetings Corporate newsEstablishments & sites

ESA Headquarters ESA ESTEC ESA ESOC ESA ESRIN ESA EAC ESA ESAC Europe's Spaceport ESA ESEC ESA ECSAT Brussels Office Washington OfficeWorking with ESA

Business with ESA ESA Commercialisation Gateway Law at ESA Careers Cyber resilience at ESA IT at ESA Newsroom Partnerships Merchandising Licence Education Open Space Innovation Platform Integrity and Reporting Administrative Tribunal Health and SafetyMore about ESA

History ESA Historical Archives Exhibitions Publications Art & Culture ESA Merchandise Kids Diversity ESA Brand Centre ESA ChampionsLatest

Space in Member States

Find out more about space activities in our 23 Member States, and understand how ESA works together with their national agencies, institutions and organisations.

Science & Exploration

Exploring our Solar System and unlocking the secrets of the Universe

Go to topicAstronauts

Missions

Juice Euclid Webb Solar Orbiter BepiColombo Gaia ExoMars Cheops Exoplanet missions More missionsActivities

International Space Station Orion service module Gateway Concordia Caves & Pangaea BenefitsLatest

Space Safety

Protecting life and infrastructure on Earth and in orbit

Go to topicAsteroids

Asteroids and Planetary Defence Asteroid danger explained Flyeye telescope: asteroid detection Hera mission: asteroid deflection Near-Earth Object Coordination CentreSpace junk

About space debris Space debris by the numbers Space Environment Report In space refuelling, refurbishing and removingSafety from space

Clean Space ecodesign Zero Debris Technologies Space for Earth Supporting Sustainable DevelopmentLatest

Applications

Using space to benefit citizens and meet future challenges on Earth

Go to topicObserving the Earth

Observing the Earth Future EO Copernicus Meteorology Space for our climate Satellite missionsCommercialisation

ESA Commercialisation Gateway Open Space Innovation Platform Business Incubation ESA Space SolutionsLatest

Enabling & Support

Making space accessible and developing the technologies for the future

Go to topicBuilding missions

Space Engineering and Technology Test centre Laboratories Concurrent Design Facility Preparing for the future Shaping the Future Discovery and Preparation Advanced Concepts TeamSpace transportation

Space Transportation Ariane Vega Space Rider Future space transportation Boost! Europe's Spaceport Launches from Europe's Spaceport from 2012Latest

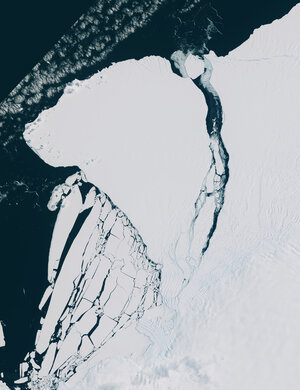

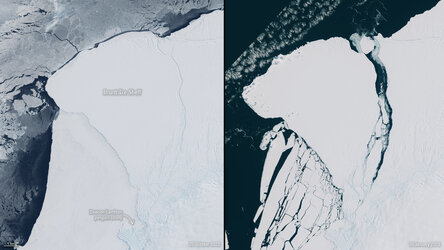

Giant iceberg breaks off Brunt Ice Shelf in Antarctica

Thank you for liking

You have already liked this page, you can only like it once!

A giant iceberg, approximately 1.5 times the size of Greater Paris, broke off from the northern section of Antarctica’s Brunt Ice Shelf on Friday 26th February. New radar images, captured by the Copernicus Sentinel-1 mission, show the 1270 sq km iceberg breaking free and moving away rapidly from the floating ice shelf.

Glaciologists have been closely monitoring the many cracks and chasms that have formed in the 150 m thick Brunt Ice Shelf over the past years. In late-2019, a new crack was spotted in the portion of the ice shelf north of the McDonald Ice Rumples, heading towards another large crack near the Stancomb-Wills Glacier Tongue.

This latest rift was closely monitored by satellite imagery, as it was seen quickly cutting across the ice shelf. Recent ice surface velocity data derived from Sentinel-1 data indicated the region north of the new crack to be the most unstable – moving around 5 m per day. Then, in the early hours of Friday 26th, the newer crack widened rapidly before finally breaking free from the rest of the floating ice shelf.

ESA’s Mark Drinkwater said, “Although the calving of the new berg was expected and forecasted some weeks ago, watching such remote events unfold is still captivating. Over the following weeks and months, the iceberg could be entrained in the swift south-westerly flowing coastal current, run aground or cause further damage by bumping into the southern Brunt Ice Shelf. So we will be carefully monitoring the situation using data provided by the Copernicus Sentinel-1 mission.”

Although currently unnamed, the iceberg has been informally dubbed ‘A-74’. Antarctic icebergs are named from the Antarctic quadrant in which they were originally sighted, then a sequential number, then, if the iceberg breaks, a sequential letter.

The calving does not pose a threat to the presently unmanned British Antarctic Survey’s Halley VI Research Station, which was re-positioned in 2017 to a more secure location after the ice shelf was deemed unsafe.

Routine monitoring by satellites offer unprecedented views of events happening in remote regions like Antarctica, and how ice shelves manage to retain their structural integrity in response to changes in ice dynamics, air and ocean temperatures. The Copernicus Sentinel-1 mission carries radar, which can return images regardless of day or night and this allows us year-round viewing, which is especially important through the long, dark, austral winter months.

-

CREDIT

contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2021), processed by ESA -

LICENCE

CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO or ESA Standard Licence

(content can be used under either licence)

Sentinel-2 captures Antarctica’s new iceberg

Brunt Ice Shelf and the Dawson-Lambton penguin colony

A-74 iceberg near collision with Brunt Ice Shelf

Iceberg larger than London breaks off Brunt

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland