Accept all cookies Accept only essential cookies See our Cookie Notice

About ESA

The European Space Agency (ESA) is Europe’s gateway to space. Its mission is to shape the development of Europe’s space capability and ensure that investment in space continues to deliver benefits to the citizens of Europe and the world.

Highlights

ESA - United space in Europe

This is ESA ESA facts Member States & Cooperating States Funding Director General Top management For Member State Delegations European vision European Space Policy ESA & EU Space Councils Responsibility & Sustainability Annual Report Calendar of meetings Corporate newsEstablishments & sites

ESA Headquarters ESA ESTEC ESA ESOC ESA ESRIN ESA EAC ESA ESAC Europe's Spaceport ESA ESEC ESA ECSAT Brussels Office Washington OfficeWorking with ESA

Business with ESA ESA Commercialisation Gateway Law at ESA Careers Cyber resilience at ESA IT at ESA Newsroom Partnerships Merchandising Licence Education Open Space Innovation Platform Integrity and Reporting Administrative Tribunal Health and SafetyMore about ESA

History ESA Historical Archives Exhibitions Publications Art & Culture ESA Merchandise Kids Diversity ESA Brand Centre ESA ChampionsLatest

Space in Member States

Find out more about space activities in our 23 Member States, and understand how ESA works together with their national agencies, institutions and organisations.

Science & Exploration

Exploring our Solar System and unlocking the secrets of the Universe

Go to topicAstronauts

Missions

Juice Euclid Webb Solar Orbiter BepiColombo Gaia ExoMars Cheops Exoplanet missions More missionsActivities

International Space Station Orion service module Gateway Concordia Caves & Pangaea BenefitsLatest

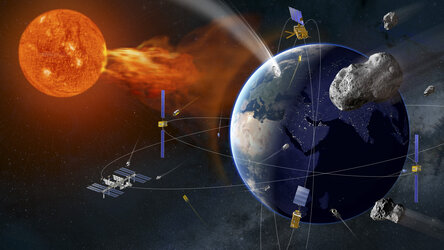

Space Safety

Protecting life and infrastructure on Earth and in orbit

Go to topicAsteroids

Asteroids and Planetary Defence Asteroid danger explained Flyeye telescope: asteroid detection Hera mission: asteroid deflection Near-Earth Object Coordination CentreSpace junk

About space debris Space debris by the numbers Space Environment Report In space refuelling, refurbishing and removingSafety from space

Clean Space ecodesign Zero Debris Technologies Space for Earth Supporting Sustainable DevelopmentLatest

Applications

Using space to benefit citizens and meet future challenges on Earth

Go to topicObserving the Earth

Observing the Earth Future EO Copernicus Meteorology Space for our climate Satellite missionsCommercialisation

ESA Commercialisation Gateway Open Space Innovation Platform Business Incubation ESA Space SolutionsLatest

Enabling & Support

Making space accessible and developing the technologies for the future

Go to topicBuilding missions

Space Engineering and Technology Test centre Laboratories Concurrent Design Facility Preparing for the future Shaping the Future Discovery and Preparation Advanced Concepts TeamSpace transportation

Space Transportation Ariane Vega Space Rider Future space transportation Boost! Europe's Spaceport Launches from Europe's Spaceport from 2012Latest

Mount Aso, Japan

Thank you for liking

You have already liked this page, you can only like it once!

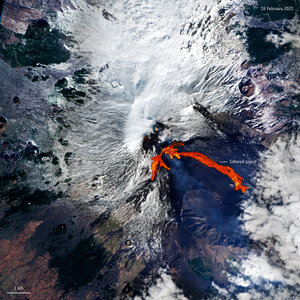

Mount Aso, the largest active volcano in Japan, is featured in this image captured on 1 January 2022 by the Copernicus Sentinel-2 mission.

Zoom in to see this image at its full 10 m resolution or click on the circles to learn more about the features in it.

Located in the Kumamoto Prefecture on the nation’s southernmost major island of Kyushu, Mount Aso rises to an elevation of 1592 m. The Aso Caldera is one of the largest calderas in the world, measuring around 120 km in circumference, 25 km from north to south and 18 km from east to west.

The caldera was formed during four major explosive eruptions from approximately 90 000 to 270 000 years ago. These produced voluminous pyroclastic flows and volcanic ash that covered much of Kyushu region and even extended to the nearby Yamaguchi Prefecture.

The caldera is surrounded by five peaks known collectively as Aso Gogaku: Nekodake, Takadake, Nakadake, Eboshidake, Kishimadake. Nakadake is the only active volcano at the centre of Mount Aso and is the main attraction in the region. The volcano goes through cycles of activity. At its calmest, the crater fills with a lime green lake which gently steams, but as activity increases, the lake boils off and disappears. The volcano has been erupting sporadically for decades, most recently in 2021, which has led to the number of visitors drop in recent years.

Not far from the crater lies Kusasenri: a vast grassland inside the mega crater of Eboshidake. Active just over 20 000 years ago, the crater has been filled with volcanic pumice from other eruptions, with magma still brewing a few kilometres below. Rainwater often accumulates on the plain forming temporary lakes. The pastures are used for cattle raising, dairy farming and horse riding.

One of the nearest populated cities is Aso, visible around 8 km north from the volcano, and has a population of around 26 000 people.

There are 110 active volcanoes in Japan, of which 47 are monitored closely as they have erupted recently or shown worrying signs including seismic activity, ground deformation or emissions of large amounts of smoke.

Satellite data can be used to detect the slight signs of change that may foretell an eruption. Once an eruption begins, optical and radar instruments can capture the various phenomena associated with it, including lava flows, mudslides, ground fissures and earthquakes. Atmospheric sensors on satellites can also identify the gases and aerosols released by the eruption, as well as quantify their wider environmental impact.

The image is also featured on the Earth from Space video programme.

-

CREDIT

contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2022), processed by ESA -

LICENCE

CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO or ESA Standard Licence

(content can be used under either licence)

Earth from Space: Mount Aso, Japan

Volcanic eruptions in Japan captured by Envisat

Mount Semeru erupts

Etna erupts

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland