Cluster muscles back from deep hibernation

On 15 September, flight controllers at ESA's Space Operations Centre watched tensely as 'Rumba', No. 1 in the four-spacecraft fleet, was switched into a low-power, deep hibernation mode. The aim was to survive a challenging eclipse.

Each year, in autumn, the Cluster fleet must pass several times through the Earth's shadow while the spacecraft orbit at apogee, or maximum altitude above the Earth. During these eclipses, which last about three hours each, sunlight is blocked by the Earth and the spacecraft solar panels cannot generate electricity.

Electrical power is then provided by batteries, one key requirement being to constantly run heaters, which keep the spacecraft warm, preventing damage to electronics and fuel pipes; battery power is also used to run the onboard computer and maintain spacecraft control.

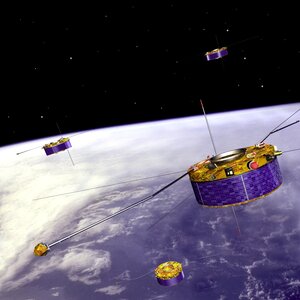

Cluster fleet in six-year cosmic dance

However, the Cluster fleet, launched in mid-2000 (and named 'Rumba', 'Salsa', 'Samba,' and 'Tango'), has now been in orbit for over six years. The spacecraft, initially built for a three-year mission, are starting to age. Batteries, in particular, are an issue.

This year, spacecraft No. 1, Rumba, which was largely built from parts left over from the first, ill-fated 1996 Cluster mission (all four satellites were lost due to launcher failure) had the most severe battery problems; three out of five have already been declared non-operational for nominal use and one has a high leakage current.

As a result, mission engineers forecast that only about 10 ampere-hours (A·h) of battery capacity would be available onboard Rumba during eclipse season, compared to the 20 A·h required.

The pending power shortfall was recognized in 2005, and an interdisciplinary team of engineers comprising representatives from the Flight Control Team at the European Space Operations Centre (ESOC), scientists at ESA's Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC) and the spacecraft's builder was established to devise a solution.

The team created a computer model of the spacecraft's thermal behaviour to identify how, exactly, it could survive eclipses with reduced, or even with no, active heaters.

There were also issues with the on-board computer, designed to restart itself automatically in the event that power is ever lost.

"The most difficult aspect was to find a safe method to switch off the onboard computer, deactivating its auto-recovery function and then to be able to wake it up again from its 'artificial coma' after the eclipse," said Juergen Volpp, Spacecraft Operations Manager at ESOC, in Darmstadt, Germany.

The team even looked at Rumba's non-operational batteries to see if a little extra power could be coaxed out of them; a solution was finally found by reducing on-board power usage to just a trickle knowing that the three-hour eclipses wouldn't be long enough for the spacecraft to totally freeze up.

Rumba would, in effect, be put into deep hibernation.

'Decoder-only' mode enabled deep hibernation

To solve the tricky computer problem, engineers eventually hit upon the idea of maintaining power during the eclipses only to the decoder, which maintains the spacecraft's 'listening' function, or its ability to understand commands. This component needs only a trickle of current and would be essential to command the computer to restart once the eclipse was over.

However, there was no way to fully validate this unique 'decoder-only' hibernation mode from the ground, and even after an intensive testing phase prior to the start of last month's eclipse season, engineers were still not fully certain that Rumba would roll through successfully.

Thus, on the night of 15/16 September, with Cluster speeding through Earth's shadow between 95 000 and 103 000 km from the planet, spacecraft controllers huddled tensely in the mission's Dedicated Control Room at ESOC for the first live implementation of decoder-only mode.

Rumba powers down

Almost everything onboard Rumba was completely shut down, with power fed only to the decoder so as to receive the wake-up signal.

Controllers communicated with Rumba via the 35-metre ESA ground station in New Norcia, Australia, selected because this station had visibility of the spacecraft both when it entered and left the eclipse zone.

"The switch-off commands had to be sent in real time; the transmitter off first, then the on-board computer was switched to operate 'in the blind', that is, with no telemetry from the spacecraft to confirm that the commands had been executed," said Volpp.

Without a peep, Rumba powered itself down and then sped into the eclipse zone while engineers began a long, two-and-one-half hours of silent waiting. Tension in the Cluster control room was palpable.

Next, ESOC engineers, who control all ESA stations remotely from Germany, commanded the giant deep-space New Norcia antenna to point to the spot in the sky where Rumba was expected to emerge from the eclipse. When the predicted eclipse passage ended at 22:13 UTC (00:13 CEST), engineers sent commands, again 'in the blind', to wake the on-board computer.

Controllers on the ground had to wait one minute for the computer to restart itself, plus four seconds of telemetry processing and signal travel time. "We never thought that sixty-four seconds could seem so long," said Volpp.

Eclipse over, Rumba grabs the wake-up signal

But the meticulous preparations and months of planning paid off handsomely as Rumba emerged from the shadow, grabbed the wake-up signal and powered up its computer just as expected; controllers quickly verified that nothing onboard had cooled below acceptance temperatures, and all systems were back in operation a few hours later.

The strategy was again proven two days later during the next - and longest - eclipse, early on 18 September.

This time, the special decoder-only hibernation mode ran for an additional 30 minutes and the spacecraft again restarted without trouble.

The last eclipse was successfully negotiated on 20 September and the Cluster fleet is now back in nominal operation, continuing one of ESA's most successful astrophysics missions.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland