Euclid calling: downloading the Universe

In brief

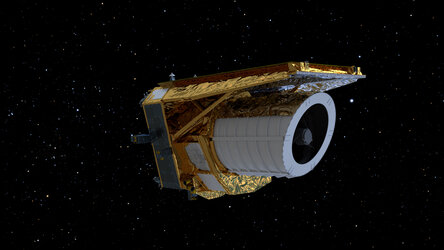

Euclid, ESA’s newest science mission, will soon begin capturing faint light from the early universe to uncover the secrets of dark matter and dark energy. The spacecraft’s instruments will capture light that has been travelling for 10 billion years and it will then need to transmit an unprecedented volume of data back to Earth – 100 GB every day for six years. It’s taken a lot of time, effort and ingenuity, but ESA’s ‘ground segment’ is ready to download the Universe.

In-depth

Just as one hand alone can’t clap, a mission in space can’t be heard without a complex combination of physical infrastructure and data systems on Earth; for monitoring and control of the spacecraft, data management, ground stations and telecommunication networks.

The scale and complexity of the Euclid mission will place high demands on ESA’s ground operations, and the Agency has been getting ready.

“Through years of technological advancements, standardisation efforts and the operational adoption of innovative engineering solutions we have successfully tackled the challenges for the ground segment of this extraordinary mission,” says Mariella Spada, Head of Ground Systems Engineering and Innovation at ESA.

Creating a conduit for Euclid’s science data

Every science mission has its own unique constraints and requirements depending on what it hopes to achieve over its lifetime. In the case of Euclid, it is designed to create the largest, most accurate-ever 3D map of the Universe. Euclid’s instruments collect ultra-accurate images in order to identify faint distortions in the shape of very distant galaxies.

Access the video

The value of these images lies in their incredible preciseness and detail. This takes the image file size into the gigabytes and leads to the key challenge for the mission’s ground segment: getting up to 100 GB of big files downlinked every day during a limited, four-hour time window.

That’s roughly twice the daily data volume that space telescopes like James Webb and Gaia transmit from the same orbit at Lagrange point 2, 1.5 million kilometres from Earth. With Euclid’s shorter ‘passes’ – talk time – with ESA ground stations, this has required the Euclid ground segment to become especially efficient to enable such a large flow from Euclid to Earth and onwards to science teams.

Upgrading deep space antennas Cebreros and Malargüe

The first step was to make it possible to sustain a high data downlink rate of up to 75 megabits per second between Euclid and the Estrack ground stations to download all its data comfortably and efficiently within four hours.

If Euclid were to transmit data in the same way as ESA's Gaia mission, also orbiting at ‘L2’, it would hopelessly congest ground stations as it sends twice the amount of data.

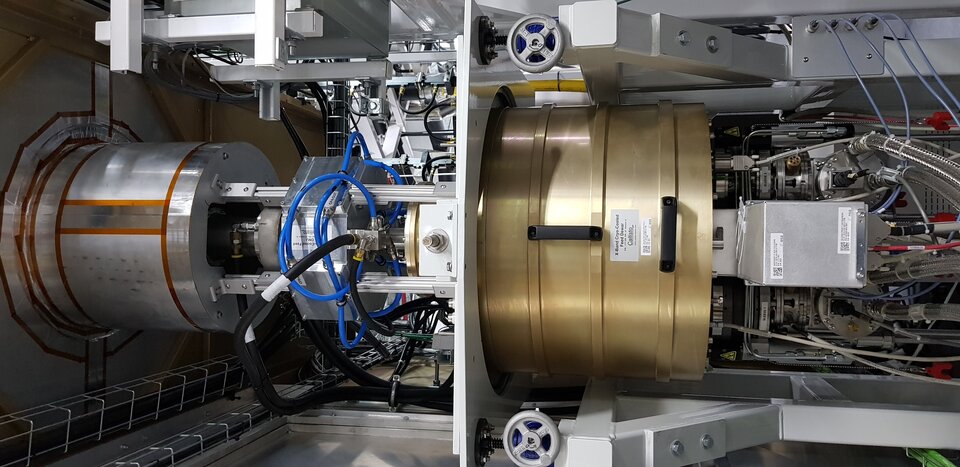

To make it possible to beam so much data in such a short time, two of ESA’s 35 m antennas had to be upgraded in various ways. First, Euclid will be ESA’s first science mission at the second Lagrange point to use the higher frequency ‘K-band’ (26 GHz), which enables a higher data rate.

“Faster communication lines were installed between the control centre in Germany and the ground stations located in Spain and Argentina. And that’s just the start of the list," says Åge-Raymond Riise, Station Coordinator for Euclid.

“We have four new cryogenically cooled ‘low-noise amplifiers’ in each station for receiving the signals from space.”

By cooling the ‘antenna feed’ to just 10 degrees above the lowest temperature possible in the Universe, increasing the amount of data that can be downlinked from spacecraft by up to 40%.

New ‘file transfer protocols’ have also been set up, a new generation of ground station modems are in use and moving mirrors have been built to route Euclid’s signal to the new equipment.

And that’s not all. This 26 GHz frequency benefits large data volumes, but the connection itself is less stable as it can lose strength due to the influence of water in the atmosphere, potentially causing data loss. Further engineering went into safeguarding against such data loss, benefiting not just Euclid but also other ESA missions that also use high frequencies.

Adding a black box to the ground stations

When receiving a transmission at a ground station, the useful data is extracted from ‘packets’ that function like a kind of envelope with instructions. The unpacked, uncoded data constitutes only about half the data Euclid sends. This is then sent on to mission control at ESA’s European Space Operations Centre (ESOC), in Darmstadt, Germany, through a private, secure connection established especially for this purpose.

Normally, the check for data completeness is done at the mission control centre, followed by sending a command to the spacecraft to retransmit data if necessary.

“In this case, the link between Euclid itself and the ground stations at Cebreros or Malargüe is much faster than the connection from the ground stations to mission control at ESOC,” explains Arek Kowalczyk, Euclid Data Systems Manager.

“We can’t afford to wait until all data has arrived at the mission control system to check if any part is missing. Instead, we developed a piece of software that runs on a Euclid-dedicated machine at the ground station. It consolidates the parts of a data file and forwards only the instructions concerning any missing data to the mission control system at ESOC, from where they can request the missing parts to be retransmitted to ground. Only once the file is complete, is it transferred to ESOC.”

This automated solution avoids data loss and allows any required retransmission to be performed automatically.

Dragging and dropping files to space

Euclid’s large images inspired a new on-board data handling system, meaning it can handle any kind of files and not only the usual data packets which have stringent data formatting requirements.

The flight controllers now have a much more intuitive, graphical interface, lowering complexity and reducing both the potential for human error and the amount of training required. It even allows the operators to drag and drop files to upload to, or download from, Euclid in space.

Most importantly perhaps, scientists don’t need to format their data in a specific way. They can have their instruments create whatever file format works best for them, and they receive their files exactly as they want them.

Keeping up with Euclid

Euclid’s launch went smoothly and commissioning continues, but for everyone in the data operations teams, the most demanding time is still ahead.

It will be a relentless task to keep up with Euclid, processing large amounts of data in the tight time windows during ground station passes, but it's one they are more than ready for.

“We are now fully prepared to download the 'Universe' from Euclid,” says Mariella Spada. “This is the result of the hard work and resourcefulness of the team, along with many colleagues from ESA and beyond who contributed to this success.”

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland