Navigating a very close approach

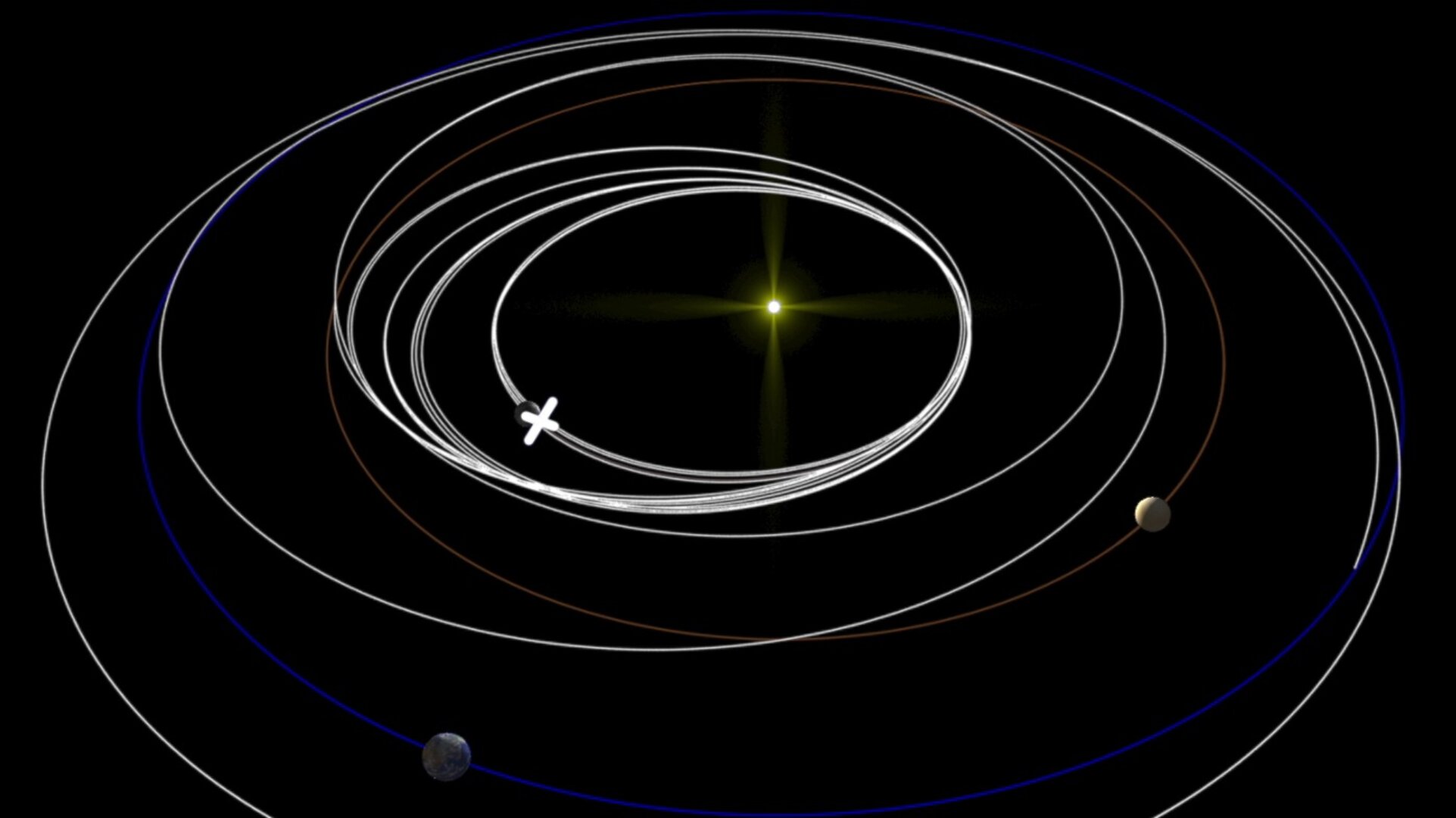

Tonight, BepiColombo will perform the first of six Mercury flybys, each honing the spacecrafts’ trajectory with the ultimate goal of shedding enough energy – after its two years ‘falling’ towards the Sun – to be caught by the innermost planet’s gravity and remain in Mercurial orbit.

This first Mercury flyby will alter the spacecraft's velocity by 2.1 km/s with respect to the Sun, with the spacecraft passing just 198 km from the planet’s surface – half the altitude of the International Space Station – at 01:34 CEST on the morning of 2 October.

For all of this to happen, BepiColombo must approach the planet from precisely the right position, and this has taken months of meticulous planning from the Flight Dynamics experts at ESA's mission control in Darmstadt, Germany.

Ultra-precise navigation

Access the video

Gravitational flybys require extremely precise deep-space navigation work, ensuring the spacecraft is on the correct approach trajectory. For this flyby, the requirement is for BepiColombo to fly just 200 kilometres from Mercury at its closest point, and here every kilometre makes a difference.

To make things difficult, BepiColombo is more than 100 million kilometres away from Earth, travelling at a velocity of 54 km/s with respect to the Sun, with signals taking 350 seconds (about six minutes) to travel from us to the mission, at the speed of light.

“Because of the remarkable precision of measurements from our network of ground stations and antennas all over the globe and the continuous efforts of the Flight Dynamics Navigation Team, our current knowledge of BepiColombo’s position is accurate to about 500 metres, and we know its velocity to the nearest millimetre per second,” explains Frank Budnik, Flight Dynamics Manager of BepiColombo at ESA’s ESOC Operations Centre.

A very close approach

One week after BepiColombo’s latest flyby of Venus on 10 August, a correction manoeuvre was performed to nudge the craft a little for this first flyby of Mercury.

At the moment, BepiColombo is on track to pass Mercury at an altitude of 198 km. Given the cosmic scales involved, being on target to within just two kilometres is no easy feat. But because precision matters, that difference of 2 kilometres can be corrected using the spacecraft’s electric propulsion system after the flyby.

Manoeuvre slots are always built into the scheduling to allow teams on the ground frequent windows to keep spacecraft on track. Because the initial burn after Venus was so accurate, the third flyby of nine in BepiColombo’s long journey, no further corrections were needed on route to Mercury.

Space on Earth

Since 2005, when ESA’s second deep space antenna in Cebreros came into operation, the Agency has used an extremely precise navigation technique called ‘delta-DOR’. The bat-sonar-like method tells us where spacecraft are, how fast they’re travelling and in what direction, accurate to within a few hundred metres, even at a distance of 100 000 000 km.

One deep space station can tell you the distance to your spacecraft and how quickly it is moving along the line-of-sight, but it needed two stations for a complete picture of interplanetary motion, using the slightly different view from each ground station to get the spacecraft’s ‘perpendicular’ motion.

Now, ESA is preparing to build its fourth deep space station in New Norcia, Australia, increasing the ability of the Estrack network to be there for missions in flight now and in the future.

Follow the flyby

Follow @Esaoperations and @bepicolombo together with @ESA_Bepi, @ESA_MTM and @JAXA_MMO for updates.

The first image is expected to be released early in the morning of Saturday 2 October (provisionally 08:00 CEST); subsequent images may be released later in the day on Saturday and/or Monday 4 October. Additional science commentary may also be available in the week following the flyby. Timings subject to change depending on actual spacecraft events and image availability.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland