Sabotaging Juice

In brief

It’s a few hours after Juice's launch, and the mission to explore Jupiter's icy moons is in trouble. At the end of his shift, which included two unexplained emergency Safe Modes, Spacecraft Operations Manager Ignacio Tanco looks defeated and sighs, “what a mess”. We are mid-way through one of the most stressful simulations the Flight Control Team has had, but two people at ESA’s mission control have had a particularly enjoyable day.

In-depth

Sat in a windowless office beneath ESA’s Main Control Room in Darmstadt, Germany, Petr and Filipe have complete control over the Juice spacecraft and ESA’s deep space ground stations across the globe – and they take full advantage.

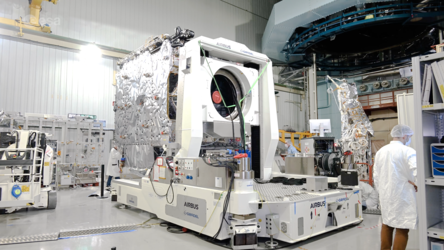

These aren’t the real 35-metre antennas or the actual spacecraft (currently in Kourou, French Guiana), but a complex simulator. For teams that will really fly Juice, it all looks, feels and behaves just like the real thing. The ‘problem’ for them is, it keeps going wrong.

Simulations take place here at the European Space Operations Centre in the months before any mission flies. They vary, testing different elements of various teams’ abilities; from the functioning of the spacecraft to external threats like solar radiation and debris, and more human issues like team cohesion, confidence or sickness. Simulations are designed to make sure any problem that happens in space can be confidently resolved on the ground.

In the current simulation, the Juice Red Team is ‘on console’. This is the team that will be on deck for 12 hours seeing the mission through lift-off and separation from its Ariane 5 rocket, and as it wakes up from the rigors of launch.

It’s not long to go before Ignacio must hand over to his counterpart, Angela, Spacecraft Operations Manager for the Blue Team, after which he and his team have another 12 hours to rest before they return to the Main Control Room. The handover is coming up, but the Red Team hasn’t yet gotten to the bottom of multiple failures on the spacecraft.

“We unite the team against us”

Access the video

Down in the 'simulations bunker', the Simulations Officers are revelling in their dastardly plan as it comes into fruition. All around them are screens showing the scenes above. They can see the concerned teams, hear their conversations and they even watch what they are doing on each of their console screens.

“It looks like we have a failure due to operator error,” says Deputy Flight Operations Director Bruno Sousa, his voice playing out from the Control Room above.

“Ha, no,” says Prime Sim Officer Petr Shlyaev. “I can see why they would think that, but they didn’t do anything wrong here. They are blaming themselves without any reason!.”

Juice has already gone into Safe Mode twice – a protective state when instruments turn off and the spacecraft runs just its most basic functions – alerting the control teams to a problem.

Recovering a spacecraft from this mode is exhausting; they must get to the root of the problem, reboot the central computer and power-off several units, all with low visibility on the state of the spacecraft. It takes a lot of work to get back to nominal operations.

As the team tries to get to the root of Juice's issues, the Simulations Officers below continue commanding the simulator, listening in on their responses and watching how they handle these complex, unideal scenarios.

“One of our primary goals is to unite the team, and one of the several ways we do it is by uniting them against us,” says Filipe Metelo, Deputy Sim Officer for Juice.

“For this simulation, we really wanted to test the two teams’ ability to handle errors as they arise just before a handover, to test how they communicate what has happened to the next team who will be taking over a mission in distress.”

“If they don’t do this properly, they – and Juice – will be punished.”

The handover

Looking a little tired, standing in front of the new team eager to hear from him, Ignacio admits, “I’m sorry to say, we are leaving you with a mess. It’s the worst I’ve seen: we have multiple undiagnosed failures that you guys need to deal with.”

Angela Dietz, managing the next team, asks, “Is Juice in Safe Mode?”

"Not quite", explains Ignacio, “It’s in Red State: something has failed but we haven’t even touched it - we don’t have a full grasp of the situation. Something is ongoing, not diagnosed, not contained, not solved. Sorry”

Despite the mess they found themselves in, by the end of the next shift the teams had got Juice back on track and onto its regular timeline (not before they had to deal with yet another Safe Mode!).

In the early stages of a mission’s life, the ‘Launch and Early Orbit Phase,’ teams are on hand 24 hours a day to welcome a mission to its new home and get it on the right path. Admittedly, the series of events created in this scenario is unlikely to happen all at once in real life – but it is possible.

For months, engineers have been flying a fake spacecraft that keeps going wrong. In just a couple of weeks, they fly the real thing. What they are doing now, helps ensure this bold mission’s success.

The real thing

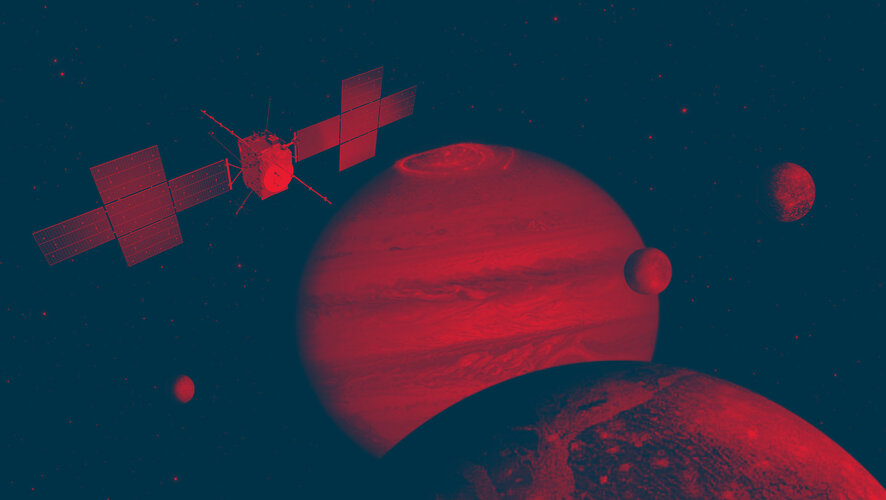

Juice is humankind’s next mission to the outer Solar System, launching on 13 April from Europe's Spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana. Its journey to Jupiter and its icy moons, Ganymede, Callisto and Europa, will be one like no other we’ve flown before.

With four Planetary flybys to get to the gas giant and 35 flybys of its icy moons, teams at ESA’s Operations Centre will be performing back-to-back critical operations with a mission that’s more massive than any we’ve flown to deep space.

This ambitious mission will characterise these moons with a powerful suite of remote sensing, geophysical and in situ instruments to discover more about these compelling destinations as potential habitats for past or present life.

Juice will monitor Jupiter’s complex magnetic, radiation and plasma environment in depth and its interplay with the moons, studying the Jupiter system as an archetype for gas giant systems across the Universe.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland