Ulysses: 12 extra months of valuable science

In 2008, Ulysses was expected to cease functioning due to weakening power. But solid engineering know-how and on-the-fly innovation have eked out an additional year of important science returns, which came to an end today.

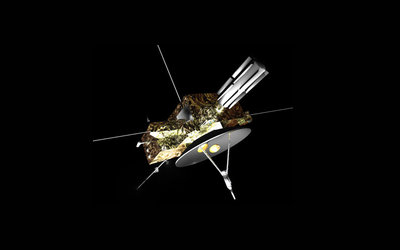

Ulysses, the joint ESA/NASA solar orbiter mission, finally ended today when ground controllers sent commands to shut down the satellite's communications. The event marks the conclusion of one of the longest and most successful space missions ever conducted.

Watch replay of Ulysses end-of-mission webcast here

The mission had been predicted to end in July 2008, when the satellite's weakened power supply was expected to fall below the minimum required to keep fuel lines from freezing, without which Ulysses would be uncontrollable. At that time, the ESA/NASA operations team planned to continue operating the spacecraft in a reduced capacity for a few more weeks.

However, through smart engineering and realtime innovation, controllers determined they could keep the lines from freezing by briefly firing the thrusters every few hours. In fact, Ulysses has continued gathering valuable scientific data throughout most of the past year - until today, after a decision was taken to end the mission due to continuing weak power and the unavailability of ground station time.

No further contact planned

Today's final communication pass via NASA's 70-m Deep Space Network started at 17:35 CEST and the satellite's radio communications switched into receive-only mode at 22:10 CEST. Last telemetry was received as expected at 22:15 CEST. No further contact with Ulysses is planned.

The joint ESA/NASA mission operations team under Nigel Angold, ESA Mission Operations Manager, monitored the final activity from the Ulysses Mission Support Area (MSA) at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), California, USA.

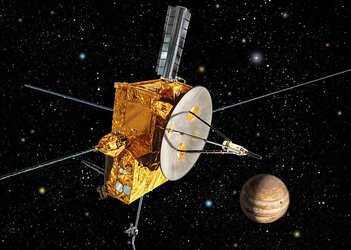

Launched by Space Shuttle Discovery on 6 October 1990, the 18-year, 8-month mission has returned a wealth of scientific data on the space environment above and below the poles of the Sun. The spacecraft and its suite of nine instruments had to be highly sensitive yet robust enough to withstand some of the most extreme conditions in the Solar System, including a close fly-by of the giant planet Jupiter.

Final ground station communication

During today's final activities, ESA and NASA mission controllers radioed up a series of instructions that progressively switched off systems on Ulysses, including:

- Switch off instrument high voltages

- Deschedule the 'Loss of Command' programme

- Perform a last Earth-pointing manoeuvre

- Switch on the redundant receiver

- Switch off the tape recorder

- Switch to the 64-bit-per-second communication rate

- Configure the S-band radio communications

- Switch off the transmitter

At the time of sending the last commands, Ulysses was located approximately 5.4 astronomical units from Earth and the one-way radio signal time was approximately 45 minutes.

An amazing adventure

"This has been an amazing adventure. Although we have said a sad farewell, Ulysses will remain a unique landmark in the exploration of space, something we can all be incredibly proud of," said Richard Marsden, ESA's Ulysses Project Scientist and Mission Manager.

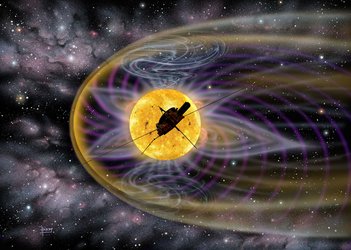

During its life, Ulysses made nearly three complete orbits of the Sun. The probe revealed for the first time the three-dimensional character of galactic cosmic radiation, energetic particles produced in solar storms and the solar wind.

Not only has Ulysses allowed scientists to map constituents of the heliosphere in space, its longevity enabled the Sun to be observed over a longer period of time than ever before.

"The Sun's activity varies with an 11-year cycle, and now we have measurements covering almost two complete cycles," said Marsden. "This long observation has led to one of the mission's key discoveries, namely that the solar wind has grown progressively weaker during the mission and is currently at its weakest since the start of the Space Age."

First commands sent in 1990

Nigel Angold, ESA's Ulysses Mission Operations Manager, said that a lot has changed since the first commands were sent to Ulysses as it orbited the Earth inside Discovery's payload bay back in October 1990.

"But what's remarkable is that many of the people involved then are here today to send the last commands," he added. "A half-dozen of the team have worked on Ulysses for its entire life - this mission has been sufficiently challenging and inspiring for talented people to dedicate significant portions of their careers to it. Also, a number of those who have moved on to other jobs at JPL are joining us to celebrate the end of this unique mission."

Longest-running ESA-operated spacecraft

Earlier in June, the Ulysses Mission Team received a NASA Group Achievement Award. Another milestone was reached on 10 June when Ulysses, having operated for 18 years and 246 days, became the longest-running ESA-operated spacecraft, overtaking the International Ultraviolet Explorer (IUE).

Following today's shutdown, Ulysses flight data will be archived and available to future ESA and NASA mission teams for reference; the mission's scientific data are already being stored in the Ulysses science data archives at ESTEC, ESA's technical centre, and at NASA's National Space Science Data Center (NSSDC).

Notes for editors:

During its life, Ulysses was operated by a joint ESA/NASA team at NASA/JPL. ESA managed the mission operations and provided the spacecraft, built by Dornier Systems, Germany (now Astrium). NASA provided the Space Shuttle Discovery for launch and the inertial upper stage and payload-assist module to put Ulysses in its correct orbit. NASA also provided the radioisotope thermoelectric generator which powers the spacecraft and payload, and the NASA Deep Space Network (DSN) was responsible for communicating with the satellite. Teams from universities and research institutes in Europe and the United States provided the nine science instruments.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland