Why is BepiColombo back?

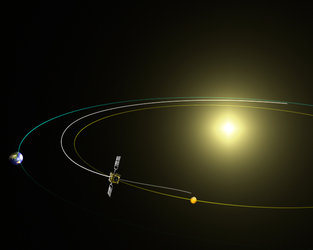

BepiColombo is on its way to Mercury, but for some reason that brings it back to Earth.

On 10 April 2020, BepiColombo will make a flyby of Earth, coming within just a couple of thousand kilometres of our planet’s outer atmosphere. Why? The spacecraft needs to shed ‘orbital energy’, and it will use our planet’s gravity to do so.

Access the video

According to Newton’s first law of motion, objects travel in a straight line, unless an external force makes them stop or change direction. Planets would travel in straight lines too, if not bound by the immense gravitational pull of massive stars.

In space, spacecraft rely on thrust from their own engines to speed up, slow down, or change direction – or even better, they can use the gravity of massive bodies they encounter along the way, like planets.

Gravity is free

The more gravity a spacecraft can take advantage of, the less fuel it needs on board, and the more scientific instruments it can carry – and BepiColombo is carrying a lot of instruments.

By flying close to planets as they sweep through space, a spacecraft can use their enormous gravitational pull to ‘exchange‘ a little of their ‘orbital energy’. The larger the orbit a spacecraft, or planet, is travelling in, the greater its orbital energy.

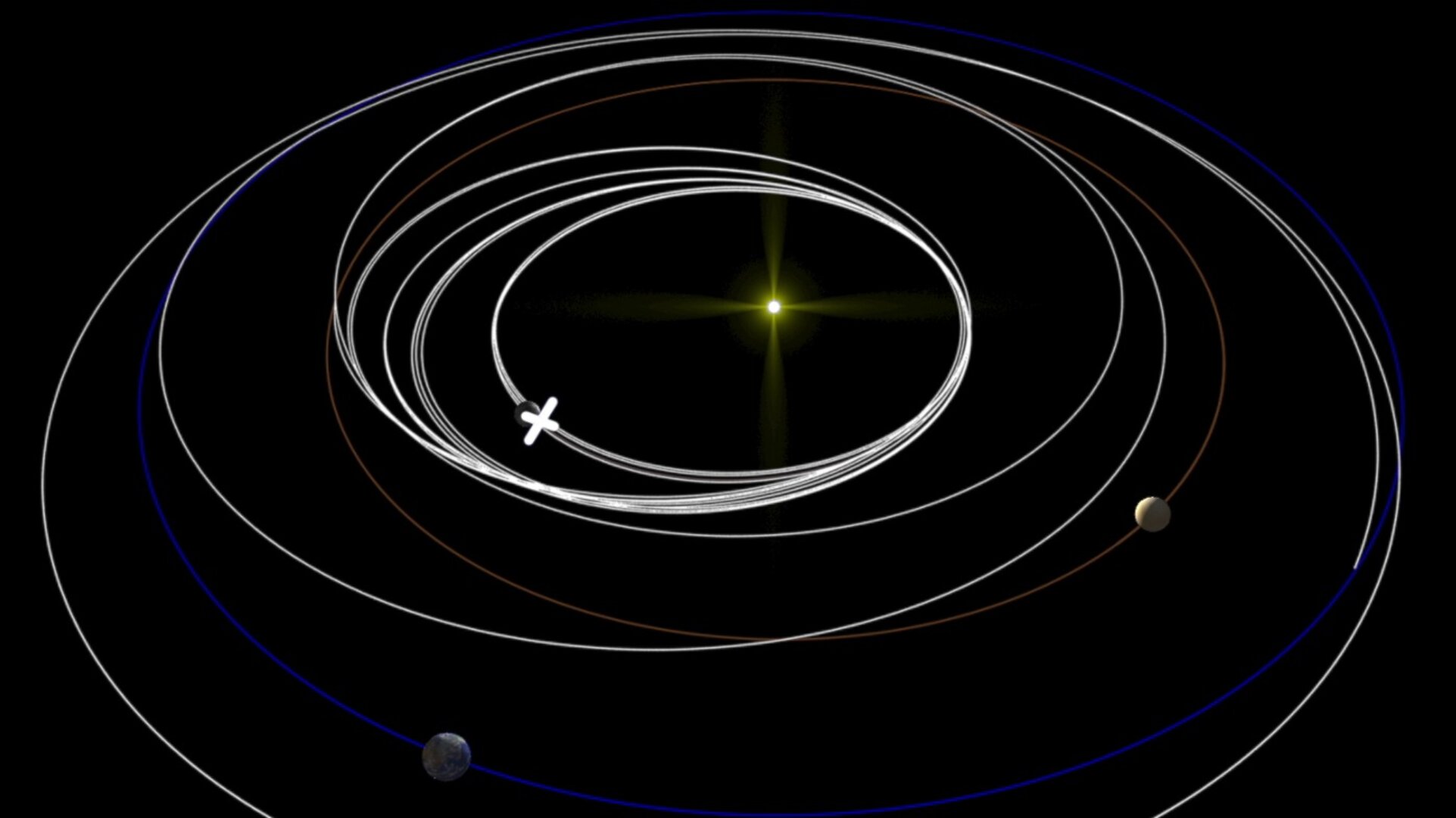

To get to Mercury, BepiColombo has to match its much smaller orbit (the smallest of all the planets in the Solar System), and to do so it has to shed some of its orbital energy.

With careful planning, depending on when, where and in what direction the spacecraft approaches, the gravitational pull of a speeding planet can change its direction and speed, without using any fuel at all.

Slowing down for Mercury

The upcoming Earth flyby will be BepiColombo's first and only visit home before it performs two more gravity-assists at Venus – the first one in October, the second one next year – and six at the scorched planet itself. It will enter Mercury’s orbit in 2025.

"During this milestone flyby, BepiColombo will use Earth to reduce its orbital energy and change its trajectory, bringing it toward the inner solar System,” explains Elsa Montagnon, BepiColombo Spacecraft Operations Manager for ESA.

“Thanks to this manoeuvre, BepiColombo will slow down by almost five kilometres a second, putting it on track to visit Earth’s ‘twin’ of a similar size, but very different composition, Venus”.

Several small trajectory correction manoeuvres have been executed before the flyby, and one is expected after, using the electric blue ion propulsion system of the Mercury Transfer Module, the ESA-made ‘bus’ carrying the two science orbiters that make up the mission, ESA’s Mercury Planetary Orbiter and JAXA’s Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter, also known as Mio.

Access the video

“The speed at which BepiColombo orbits the Sun will be much slower right after the swing-by on 10 April than it was before,” explains Michael Khan, Head of Mission Analysis at ESA.

“The swing-by will have robbed BepiColombo's orbit of a lot of energy, without having to fire its engines or even using much fuel. Just, instead, with clever use of the laws of physics.”

Follow the flyby

For observers in the Southern Hemisphere, or southern parts of the Northern Hemisphere, it may be possible to catch a glimpse of BepiColombo if you have a telescope or even a good pair of binoculars.

For everyone else, get live updates via @BepiColombo on Twitter, and get an idea of where the spacecraft is on the live animation that will be streamed on @esaoperations.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland