Cresting the ocean waves

Forecasting the state of the sea is important for shipping, offshore and coastal engineering, management of coastal zones and tourism. Safety and financial losses associated with rough seas are a real concern. Ocean waves slow down the passage of ships, endanger marine industries such as oil and gas extraction, damage aquaculture and offshore wind farms, and erode coastlines.

Although ocean waves have been measured by satellites since the first radar altimeter was tested on NASA's Skylab space station in 1973, the use of consolidated datasets on ocean waves for scientists and engineers is a relatively recent development.

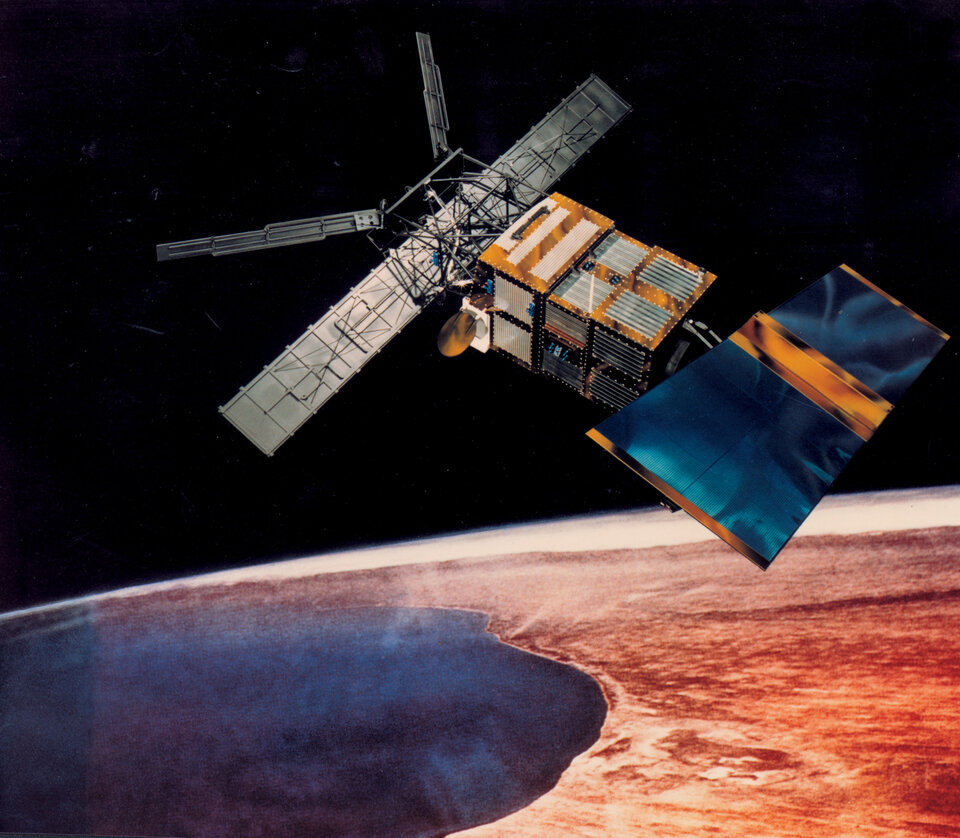

Since the launch of ESA's ERS-1 in 1991, space-based wave observations have been augmented by synthetic aperture radar (SAR) instruments, which have the unique ability to measure simultaneously wave height, wave length and direction of ocean swell systems.

Through the GlobWave project, data on waves were consolidated from 11 different satellite instruments that have been in orbit since 1985. This dataset, which is suitable for scientific research, is available at no charge. It is in a common format, quality controlled and available though a single web portal. These data are being put to work in a range of applications, from improving wave-forecast models to research into the prevalence of dangerous seas all over the world.

The ESA European Remote Sensing (ERS) satellites have been retired, but yielded amazing information about our oceans. One discovery, in 2004, was the confirmation of enormous waves – capable of sinking sturdy ships. This news was first announced on the ESA Observing the Earth site.

Once dismissed as a nautical myth, freakish ocean waves that rise as tall as ten-storey buildings have been accepted as a leading cause of large ship sinkings. Results from ESA's ERS satellites helped establish the widespread existence of these 'rogue' waves, which may have caused as many as 200 supertankers and container ships to sink between 1984 and 2004.

Mariners who survived similar encounters have had remarkable stories to tell. In February 1995 the cruiser liner Queen Elizabeth II met a 29-metre high rogue wave during a hurricane in the North Atlantic that Captain Ronald Warwick described as "a great wall of water… it looked as if we were going into the White Cliffs of Dover."

In the space of less than a week between February and March 2001 two hardened tourist cruisers – the Bremen and the Caledonian Star – had their bridge windows smashed by 30-metre rogue waves in the South Atlantic, the former ship left drifting without navigation or propulsion for a period of two hours. All the electronics were switched off on the Bremen as they drifted parallel to the waves, and until they were turned on again the crew feared the worst.

In December 2000 the European Union initiated a scientific project called MaxWave to confirm the widespread occurrence of rogue waves, model how they occur and consider their implications for ship and offshore structure design criteria. And as part of MaxWave, data from ESA's ERS radar satellites were first used to carry out a global rogue wave census.

The Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) aboard ESA's twin spacecraft ERS-1 and 2 was used to grab ‘imagettes’ of the sea surface. These small imagettes are then mathematically transformed into averaged-out breakdowns of wave energy and direction, called ocean-wave spectra. ESA makes these spectra publicly available; they are useful for weather centres to improve the accuracy of their sea forecast models.

Despite the relatively brief length of time the data covered, the MaxWave team identified more than ten individual giant waves around the globe above 25 metres in height. The data showed rogue waves also occur well away from currents, often occurring in the vicinity of weather fronts and lows. Sustained winds from long-lived storms exceeding 12 hours may enlarge waves moving at an optimum speed in sync with the wind – too quickly and they'd move ahead of the storm and dissipate, too slowly and they would fall behind.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland