How to cook a spacecraft

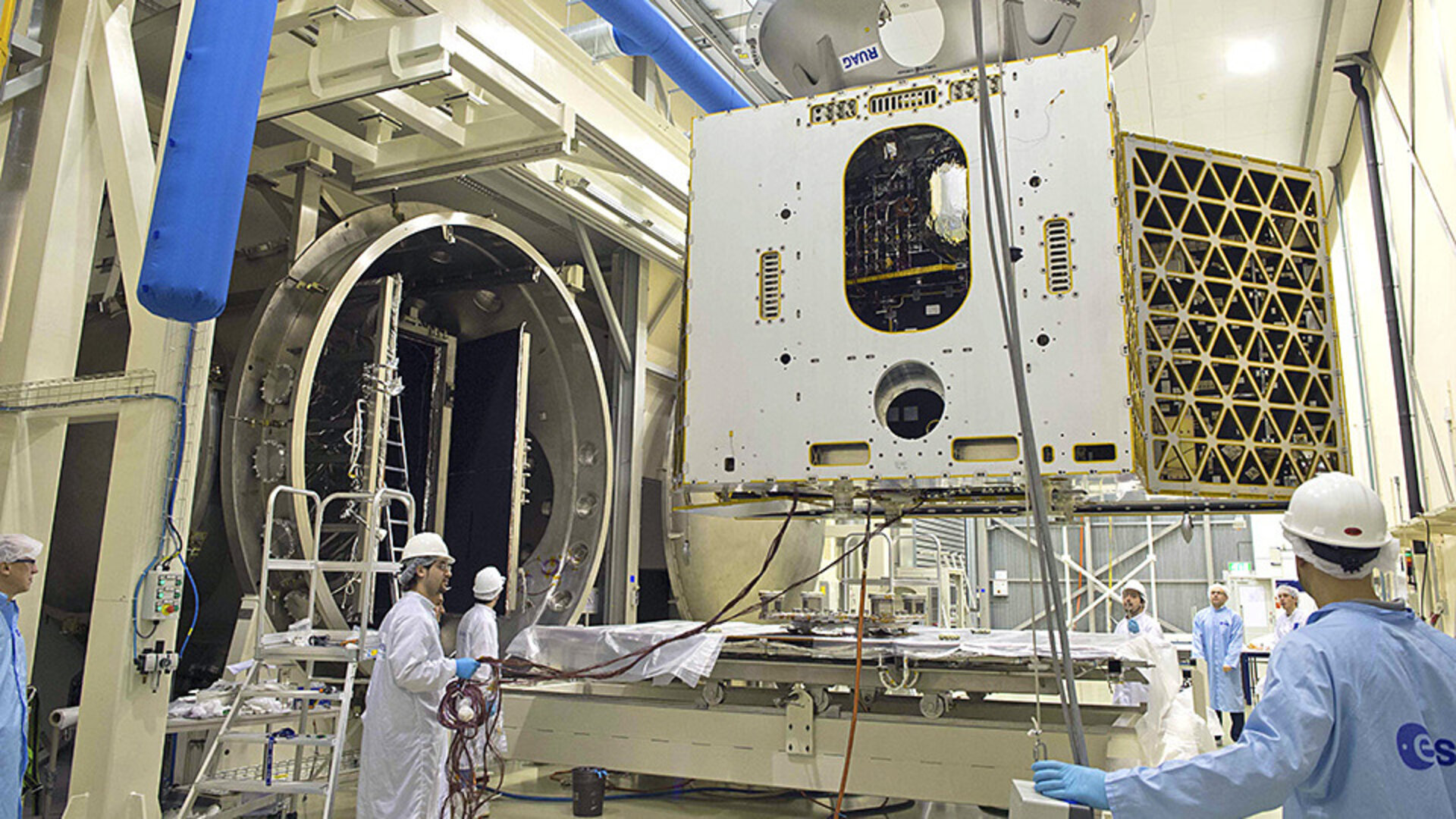

The faint aroma of hot metal filled the surrounding cleanroom as the hatch to ESA’s newest test facility was slid aside, concluding a 23-day ‘bake-out’ of the largest segment of ESA’s mission to Mercury.

Ending on the early hours of 14 February, this test ensured ESA’s Mercury Planetary Orbiter – MPO, part of the multi-module BepiColombo mission – was cleaned of potential contaminants in advance of its 2015 mission to the inner Solar System.

The bake-out took place at ESA’s technical heart, ESTEC in Noordwijk, the Netherlands, which includes a dedicated Test Centre equipped to simulate all aspects of the space environment.

MPO will fly to the innermost planet with Japan’s Mercury Magnetosphere Orbiter, riding together on ESA’s propulsion module. But not before getting cooked first.

“Being close to Mercury and experiencing high temperatures, the release of molecules from spacecraft materials is expected to occur at higher quantities than for normal satellites,” explains Jan van Casteren, BepiColombo Project Manager.

“Such molecules are a contamination threat if they condense on sensitive surfaces, so we need to minimise outgassing in order to protect our delicate scientific instrumentation on the spacecraft.”

So an initial bake-out of the various spacecraft segments is essential for cleaning purposes – in this case MPO’s ‘Proto-Flight Model’, incorporating its propulsion system and heat pipes that regulate its temperature.

A new test facility called Phenix hosted the bake-out, a 4.5 m-diameter stainless steel vacuum chamber 11.8 m long, with an inner box called the ‘thermal tent’ whose six copper walls can be heated up to 100°C or cooled via piped liquid nitrogen down to –190°C, all independent from each other.

“This test was different from more typical thermal vacuum testing because, while the sides and top of the chamber were kept heated to around 50°C, the underside remained cooled by liquid nitrogen throughout,” explains Mark Wagner, Head of ESTEC’s Test Facilities & Test Methods Section.

“This creates a ‘cold trap’ where the contaminants baked off from the satellite solidify for collection. But sustaining this environment required 1500 litres of liquid nitrogen per hour – on average three tankers were calling at ESTEC daily to top up our supply.”

The test was monitored 24 hours per day on a triple shift system, with care being taken to maintain the temperatures precisely and ensure a continuous flow of data.

Outgassing production was monitored throughout the test, and the bake-out results are now being analysed. A non-trivial amount of contaminants are expected to have been produced – ‘spoonfuls’ of material.

Now Phenix itself is being thoroughly cleaned, ready for its next customer.

“Phenix was put in place to extend the range of thermal vacuum test services on offer to ESTEC Test Centre customers,” explains Mark. “It is able to accommodate large subsystems or entire spacecraft.”

Phenix was cleared for use last December, after which preparations began immediately for BepiColombo testing.

“The chamber will be kept busy for much of the rest of this year accommodating a forthcoming batch of Galileo satellites,” Mark concludes.

“This will be more traditional testing – simulating the temperature extremes the Galileo satellites must endure throughout their 12-year working lifetimes.”

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland