Hundreds of impacts crater ESA’s Columbus science laboratory

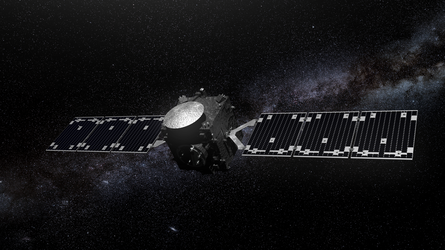

On 6 September 2018, the 17-metre arm attached to humankind’s most distant outpost began to move. Its instructions were to survey the spaceship’s European science laboratory for signs of impact damage from marauding bits of space rock or space debris.

The robotic arm camera on the International Space Station has now completed the first two scans of the outer panels of the Columbus module, in search of micro impact 'craters'.

The Columbus crater survey was requested by a European team of scientists, including Detlef Koschny, an expert from ESA's Planetary Defence Office focussing on space safety and security.

“Space is vast and mostly empty, but small space rocks are constantly passing into our local environment as well as debris from past spacecraft collisions and explosions”, explains Detlef.

The Columbus module, part of the International Space Station, is the first permanent European research facility in space, and the largest single contribution to the Station made by ESA.

Launched in February 2008, the European Columbus laboratory has been in space for ten years, but until September it had not been thoroughly checked for signs of impact damage.

In their first analysis of the data, the team found several hundred small impact craters, visible in this image (left) as tiny dents in the laboratory’s outer casing. These would have been produced by very small pieces of either natural or artificial debris, typically smaller than 1 mm in size.

“These fragments can travel at extremely fast speeds, and if larger than a centimeter in size could do a great deal of damage to the Space Station and satellites in orbit”, Detlef continues.

As was recently discovered on the Station, even a small hole in the protective casing of the Soyuz module created a noticeable loss of air pressure. This recent discovery is now thought not to be the result of an external impact, but it shows the importance of understanding how these events can happen.

Detlef concludes, “These little dents in the outer part of the Columbus module show how the space around Earth is not so empty after all. They also show what a good job the ESA-built module is doing to protect astronauts living and working in space”.

This study allows the team to better understand the density of human-made debris particles at the orbital altitude of the Space Station, in comparison to the natural micrometeorite density near Earth, both of which are important for constructing models to help us understand the risks of the meteorites marauding through space.

The recordings will also be used by ESA's Space Debris Office, who are evaluating the footage in order to characterise the craters found – an important tool for validating current models, such as ESA's Meteoroid and Space Debris Terrestrial Environment Reference (MASTER), which describes the impact risk to missions in orbit from human-made and natural debris.

Find out more about ESA’s Space Debris Office and the Agency's asteroid defence efforts – including construction of the first-ever Flyeye telescope and the ambitious planned Hera mission to test asteroid deflection.

Editor's note: This project was proposed by Gerhard Drolshagen (University of Oldenburg, D), Robin Putzar (Fraunhofer/EMI, Freiburg, D), Dieter Sabath (DLR Oberpfaffenhofen, D), and Detlef Koschny (ESA) plus other experts from TU Braunschweig, D, ESA, and NASA.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland