Weightless on Earth with Vivaldi

During missions on the International Space Station, astronauts’ bodies go through a wide array of changes due to lack of gravity - everything from vision to cardiovascular health to bone density is affected.

Though astronauts exercise and take supplements to mitigate some of these effects, understanding more about deconditioning in microgravity could allow physicians to design better treatments. This wouldn’t just be useful for spacefarers; it could also improve treatment strategies for common health conditions here on Earth.

Staying dry in a wet situation

To do this, the ESA SciSpacE team and a team of European scientists designed Vivaldi, which takes place in the MEDES Space Clinic (Institute for Space Medicine and Physiology) in Toulouse, France – one of the only facilities in Europe which can host such studies.

Vivaldi is an experiment that focuses on what’s known as dry immersion – a ground-based analogue of the effects microgravity has on the body. As the name suggests, dry immersion involves being immersed in water for long periods, while staying dry. To do this, participants are clothed in a waterproof fabric and laid in specially-designed water baths. Their body is then submerged to above the torso, with a fitted waterproof tarp keeping their arms and head above water.

During Vivaldi, participants spend five whole days in this position. Meals are taken with the assistance of a floating board and a neck pillow. For bathroom breaks and other activities that require removal from water, participants are assisted onto a trolley, maintaining their laid-back position, and temporarily removed from the water by staff.

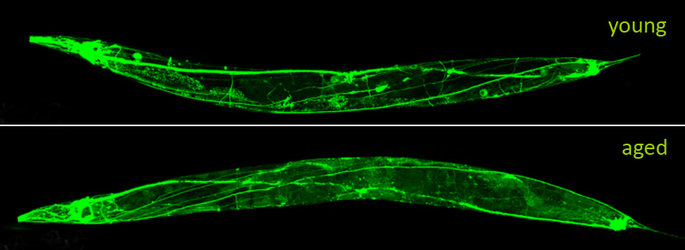

Submerging participants in this way takes weight off the body, inducing microgravity-like alterations to neurological, cardiovascular, and metabolic systems, to name just a few. Fluids within the body shift, and physiological processes begin to resemble those seen in astronauts during spaceflight.

The convenience of being on the ground, however, allows researchers to make all kinds of hands-on medical assessments, and closely monitor how systems change across the course of weightlessness. Such an analogue also allows researchers to gather data on bodily changes from more people, as well as draw firm conclusions about what they’re observing more quickly.

Microgravity on Earth?

Though dry immersion is more commonly used by Russian researchers, the ESA SciSpacE team is testing to see just how similar it is to actual spaceflight. Through Vivaldi, they hope to identify specifically what changes happen to the body during weightlessness, how long those changes take to happen, and how they compare to both spaceflight and other ground-based microgravity analogues.

“Our first objective is to use the analogue to get a better understanding on how humans physiologically, and to a certain extent psychologically, react and adapt to such an extreme stimulus,” says Angelique, ESA Discipline Lead for Life Sciences. “It's a good tool to get a better understanding of how astronauts adapt to spaceflight, and it allows us to test and validate countermeasures.”

The first leg of this experiment, Vivaldi I, featured an all-female group of participants, to fill a gap in existing research. Alongside Vivaldi II, the soon-to-begin second leg involving male participants, the data gathered will give researchers an idea of what strains microgravity places on astronauts of any sex, so that widely effective mitigation approaches can be designed

Impact beyond spaceflight

But it’s not just astronauts that benefit from this research. Research that helps us reach the Moon and Mars can also be translated to healthcare here on Earth. Understanding deconditioning using dry immersion may also help researchers and physicians to design new treatment approaches for patient populations, such as those with muscoloskeletal conditions, those who are immobilised, and the elderly.

“At ESA, we really try to focus also on that translational aspect,” shares Angelique. “If we can test countermeasures, like specific types of exercise or nutritional supplements, and we see they work well, maybe health researchers can consider testing them for specific patient populations, too.”

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland