21 April

1998: On 21 April 1998, the NASA/ESA Cassini-Huygens mission began a fly-by of Venus. As planned, the spacecraft then flew 284 kilometres above the Venusian surface. Because of Venus's distance (136 million kilometres), it took radio signals seven minutes to travel to Earth.

The tug of Venus's gravity gave the spacecraft a boost in speed of about 7 kilometres per second which would help Cassini-Huygens reach Saturn in July 2004. Leaving Venus, the spacecraft was moving at more than 141 000 kilometres per hour relative to the Sun.

Cassini-Huygens would perform three more similar gravity-assist fly-bys: Venus again in June 1999, Earth in August 1999, and Jupiter in December 2000. All the fly-bys used the gravitational pull of the target planets to give more speed to the spacecraft to help it reach Saturn. The Venusian fly-by was the lowest-altitude gravity-assist planetary pass Cassini-Huygens would make in its mission.

Science instruments on the spacecraft searched for lightning in Venus's atmosphere during the fly-by, and the radar instrument on board was activated to test a bounced signal off the surface of the planet.

1995: On 21 April 1995, Europe launched the European Remote-sensing satellite (ERS 2). It carried out ocean, land, ice, and atmospheric observations.

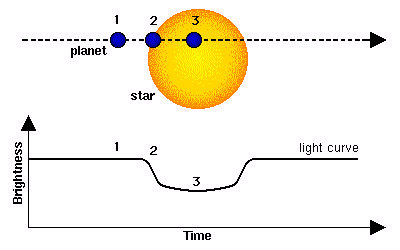

1994: On 21 April 1994, Alexander Wolszczan announced the discovery of planets outside of our own Solar System.

Dr Alexander Wolszczan, a radio astronomer at Pennsylvania State University, reported what he called 'unambiguous proof' of extrasolar planetary systems.

While scientists accepted his assessment, those hoping for evidence of planetary systems similar to our own were less than elated. Wolszczan had discovered two or three planet-sized objects orbiting a pulsar, rather than a normal star, in the Virgo constellation. A pulsar is a dense, rapidly spinning remnant of a supernova explosion.

Wolszczan made his discovery by observing regular variations in the pulsar's rapidly pulsed radio signal, indicating the planets' complex gravitational effects on the dead star. These worlds could not support life as we know it - they would be permanently bathed in high-energy radiation, leaving them barren and inhospitable.

The first discovery of a planet orbiting a star similar to the Sun came in 1995. The Swiss team of Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz of Geneva announced that they had found a rapidly orbiting body located close to a the star 51 Pegasi. Their planet was at least half the mass of Jupiter and no more than twice its mass. These announcements marked the beginning of a flood of discoveries. By the end of the twentieth century, several dozen worlds had been discovered, many the result of months or years of observation of nearby stars.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland