Landing on a cosmic iceberg

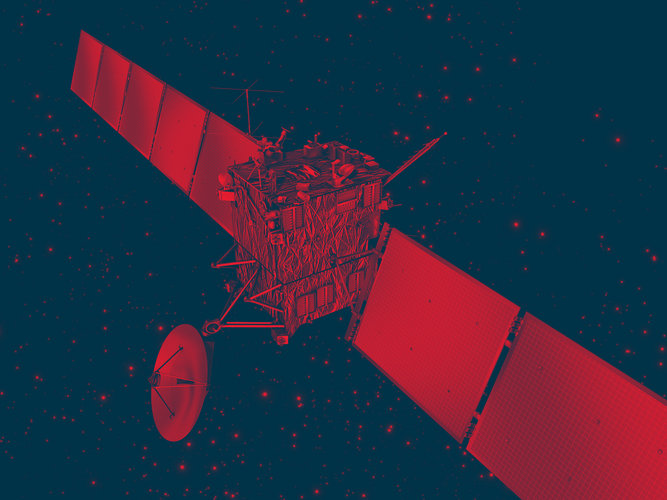

During the last 40 years, the only objects in the Solar System on which robotic spacecraft have soft-landed are the Moon, Venus, Mars and near-Earth asteroid Eros. But a decade from now, ESA's pioneering Rosetta spacecraft will land on a comet.

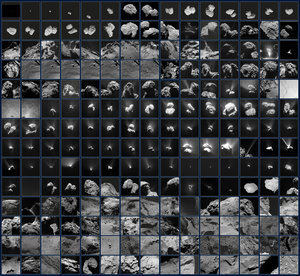

Rosetta will achieve many breakthroughs during its 10-year odyssey to a comet starting in 2004, but one of the most exciting episodes of this ambitious mission will involve the first soft landing on one of these cosmic icebergs. This landmark event will be followed by the first panoramic images from a comet's surface and the first 'in situ' analysis to find out what its ancient nucleus is made of.

The historic landing on one of the most primitive objects in the Solar System will be undertaken by a unique spacecraft which has been built by a European consortium under the leadership of the German Space Agency (DLR), together with ESA and institutes from Austria, Finland, France, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Germany and the UK.

Engineers at the European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC) in the Netherlands have recently integrated the landing gear on the 100 kg Rosetta Lander, clearing the way for the installation of the box-shaped spacecraft on the exterior of the three tonne orbiter. In the coming weeks, the two spacecraft will complete their systems tests and the lander release mechanism will be checked. Then it will be time to ship the Rosetta 'mother craft' and its small piggyback companion to the launch complex in Kourou, French Guiana.

So how will Rosetta's little Lander make its mark in the annals of space exploration? Jean-Christophe Salvignol, the Rosetta spacecraft and Lander mechanical engineer, outlined the complex procedure.

"Shortly after launch, the four main attachment points used to carry the Lander during launch are released. The Lander is then only supported by its central motor, the MSS, during all the cruise."

"In 2012, the Lander will be released from the Rosetta orbiter at an altitude of about one kilometre above the nucleus. By this time, the instruments on the orbiter will have mapped every square centimetre of the comet's surface, enabling scientists to select a suitable landing site.

"The MSS will then gently push the Lander away at crawling speed, no more than 0.5 metres per second. Once the landing gear is deployed, the spacecraft will edge towards its target, prevented from tumbling by an internal flywheel that provides stability as its spins. A single cold gas thruster will be able to provide a gradual upward push to improve the accuracy of the descent."

After a nail-biting 30-minute wait by the helpless mission team back on Earth, sensors on board the Lander will record the historic moment of touchdown. Since the nucleus is so small, its gravitational pull will be extremely weak - millions of times weaker than on Earth - causing the Lander to touch down at no more than walking pace. Nevertheless, a damping system in the landing gear will be available to reduce the shock of impact and to prevent rebound. Other events will occur in quick succession.

"Hopefully, gradient will not be a problem, since the spacecraft is designed to stay upright on a slope of up to about 30 degrees," said Jean-Christophe. "However, the Lander carries two harpoons. One of these will be fired at the moment of touchdown to anchor the spacecraft to the surface and prevent it from bouncing. Ice screws on each leg will also be rotated to bite into the nucleus and secure the Lander in place. The second harpoon will be held in reserve for use later in the mission if the first one becomes loose. "Meanwhile, the science programme will quickly get under way. In the primary phase, which relies on battery power, the most important scientific measurements will be completed. It will last in the order of 60 hours. The secondary science will be conducted using the remaining battery power and energy from the solar cells on the exterior of the Lander. The duration of this phase should be about 3 months. Anyway, no one knows precisely how long it will survive. This will depend on a number of factors: power supply, temperature or surface activity on the comet."

What we can be sure of is that Rosetta will revolutionise our knowledge of comets, providing new insights into the nature and origins of these primordial objects, the building blocks from which the planets were born.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland