Making a detour to see asteroids

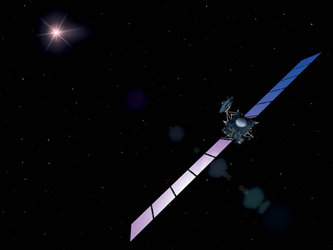

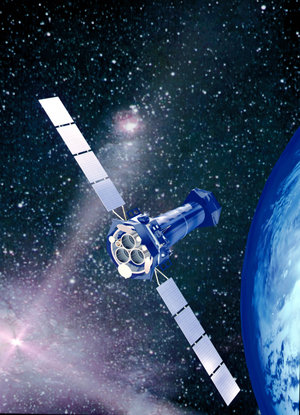

Even though it takes ten years to arrive at Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, Rosetta will not be idle for a decade. Now the mission is under way, the Rosetta scientists have decided to make a detour, to take a close look at two asteroids.

On 11 March 2004, the Rosetta Science Working Team decided that the target asteroids will be Steins and Lutetia. The ESOC Flight Dynamics team had drawn up a list of asteroids that the spacecraft could visit. Initially, it was thought it would be possible to study just one, asteroid Baetsle, with Rosetta making the fly-by in October 2008.

However, soon after the launch, the teams realised everything had gone so well that they would be able to select two targets. The orbit injection by the Ariane rocket used to launch Rosetta was so accurate that only a small amount of fuel was needed to make some tiny corrections. This released a considerable amount of the fuel budget that could be allocated to make sure that Rosetta visits two asteroids.

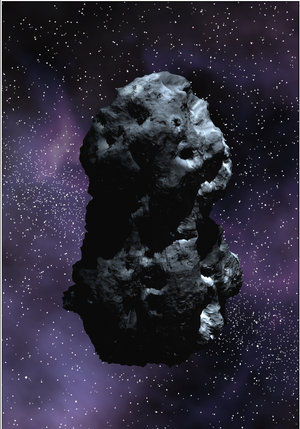

The spare fuel will now be used to make a detour for the spacecraft. First it will rendezvous with Steins, a small asteroid of just a few kilometres in diameter, on 5 September 2008. Then, it will visit asteroid Lutetia on 10 July 2010. Lutetia is a large asteroid, at 100 kilometres in diameter.

Visiting these asteroids is a perfect way to complement the science that Rosetta will perform once at its final destination, because asteroids can be thought of as cometary ‘cousins’.

Both comets and asteroids are the left-over building blocks of the planets in our Solar System. The biggest difference is that comets formed in the cold outer reaches of the Solar System. That far away, rocks and ice formed together, creating the ‘dirty snowballs’ that are today’s comets.

The asteroids formed nearer to the Sun - they and their precursors were ‘planetesimals’, small to medium-sized rocky objects just like those growing elsewhere in the early solar system or ‘solar nebula’ during planetary accretion.

Before they could form a planet, however, these bodies were gravitationally perturbed into tilted, elongated orbits. So instead of joining into a single big object, asteroids began to strike each other at high speeds, several kilometres per second, often resulting in catastrophic fragmentation and disruption rather than accretion.

There are many different types of asteroids and, to date, only a handful of them have been seen up close. Rosetta’s detour will significantly increase our knowledge of these small bodies and will also give scientists a chance to check out the instruments and techniques they will use at Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland