Gaia discovers its first supernova

While scanning the sky to measure the positions and movements of stars in our Galaxy, Gaia has discovered its first stellar explosion in another galaxy far, far away.

This powerful event, now named Gaia14aaa, took place in a distant galaxy some 500 million light-years away, and was revealed via a sudden rise in the galaxy’s brightness between two Gaia observations separated by one month.

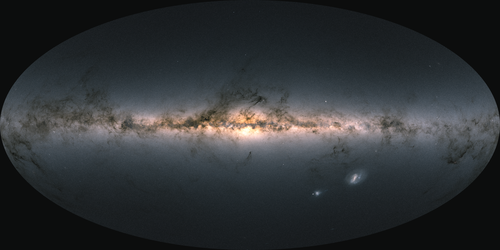

Gaia, which began its scientific work on 25 July, repeatedly scans the entire sky, so that each of the roughly one billion stars in the final catalogue will be examined an average of 70 times over the next five years.

“This kind of repeated survey comes in handy for studying the changeable nature of the sky,” comments Simon Hodgkin from the Institute of Astronomy in Cambridge, UK.

Many astronomical sources are variable: some exhibit a regular pattern, with a periodically rising and declining brightness, while others may undergo sudden and dramatic changes.

“As Gaia goes back to each patch of the sky over and over, we have a chance to spot thousands of ‘guest stars’ on the celestial tapestry,” notes Dr Hodgkin. “These transient sources can be signposts to some of the most powerful phenomena in the Universe, like this supernova.”

Dr Hodgkin is part of Gaia’s Science Alert Team, which includes astronomers from the Universities of Cambridge, UK, and Warsaw, Poland, who are combing through the scans in search of unexpected changes.

It did not take long until they found the first ‘anomaly’ in the form of a sudden spike in the light coming from a distant galaxy, detected on 30 August. The same galaxy appeared much dimmer when Gaia first looked at it just a month before.

“We immediately thought it might be a supernova, but needed more clues to back up our claim,” explains Łukasz Wyrzykowski from the Warsaw University Astronomical Observatory, Poland.

Other powerful cosmic events may resemble a supernova in a distant galaxy, such as outbursts caused by the mass-devouring supermassive black hole at the galaxy centre.

However, in Gaia14aaa, the position of the bright spot of light was slightly offset from the galaxy’s core, suggesting that it was unlikely to be related to a central black hole.

So, the astronomers looked for more information in the light of this new source. Besides recording the position and brightness of stars and galaxies, Gaia also splits their light to create a spectrum. In fact, Gaia uses two prisms spanning red and blue wavelength regions to produce a low-resolution spectrum that allows astronomers to seek signatures of the various chemical elements present in the source of that light.

“In the spectrum of this source, we could already see the presence of iron and other elements that are known to be found in supernovas,” says Nadejda Blagorodnova, a PhD student at the Institute of Astronomy in Cambridge.

In addition, the blue part of the spectrum appears significantly brighter than the red part, as expected in a supernova. And not just any supernova: the astronomers already suspected it might be a ‘Type Ia’ supernova – the explosion of a white dwarf locked in a binary system with a companion star.

While other types of supernovas are the explosive demises of massive stars, several times more massive than the Sun, Type Ia supernovas are the end product of their less massive counterparts.

Low-mass stars, with masses similar to the Sun’s, end their lives gently, puffing up their outer layers and leaving behind a compact white dwarf. Their high density means that white dwarfs can exert an intense gravitational pull on a nearby companion star, accreting mass from it until the white dwarf reaches a critical mass that then sparks a violent explosion.

To confirm the nature of this supernova, the astronomers complemented the Gaia data with more observations from the ground, using the Isaac Newton Telescope (INT) and the robotic Liverpool Telescope on La Palma, in the Canary Islands, Spain.

A high-resolution spectrum, obtained on 3 September with the INT, confirmed not only that the explosion corresponds to a Type Ia supernova, but also provided an estimate of its distance. This proved that the supernova happened in the galaxy where it was observed.

“This is the first supernova in what we expect to be a long series of discoveries with Gaia,” says Timo Prusti, ESA’s Gaia Project Scientist.

Supernovas are rare events: only a couple of these explosions happen every century in a typical galaxy. But they are not so rare over the whole sky, if we take into account the hundreds of billions of galaxies that populate the Universe.

Astronomers in the Science Alert Team are currently getting acquainted with the data, testing and optimising their detection software. In a few months, they expect Gaia to discover about three new supernovas every day.

In addition to supernovas, Gaia will discover thousands of transient sources of other kinds – stellar explosions on smaller scale than supernovas, flares from young stars coming to life, outbursts caused by black holes that disrupt and devour a nearby star, and possibly some entirely new phenomena never seen before.

“The sky is ablaze with peculiar sources of light, and we are looking forward to probing plenty of those with Gaia in the coming years,” concludes Dr Prusti.

More information

For details about Gaia's Science Alerts see the Notes for Editors.

For further information, please contact:

Markus Bauer

ESA Science and Robotic Exploration Communication Officer

Tel: +31 71 565 6799

Mob: +31 61 594 3 954

Email: markus.bauer@esa.int

Timo Prusti

Gaia Project Scientist

Email: timo.prusti@esa.int

Simon Hodgkin

Institute of Astronomy

Cambridge, UK

Tel: +44 1223 766657

Email: sth@ast.cam.ac.uk

Lukasz Wyrzykowski

Warsaw University Astronomical Observatory

Warsaw, Poland

Tel: +48 608 648817

Email: lw@astrouw.edu.pl

Nadejda Blagorodnova

Institute of Astronomy

Cambridge, UK

Tel: +44 1223 337548

Email: nblago@ast.cam.ac.uk

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland