Herschel links Jupiter’s water to comet impact

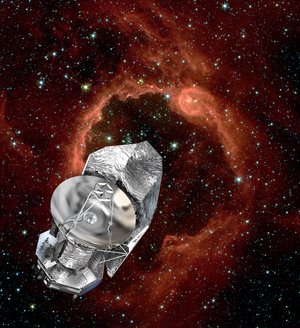

ESA’s Herschel space observatory has solved a long-standing mystery as to the origin of water in the upper atmosphere of Jupiter, finding conclusive evidence that it was delivered by the dramatic impact of comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 in July 1994.

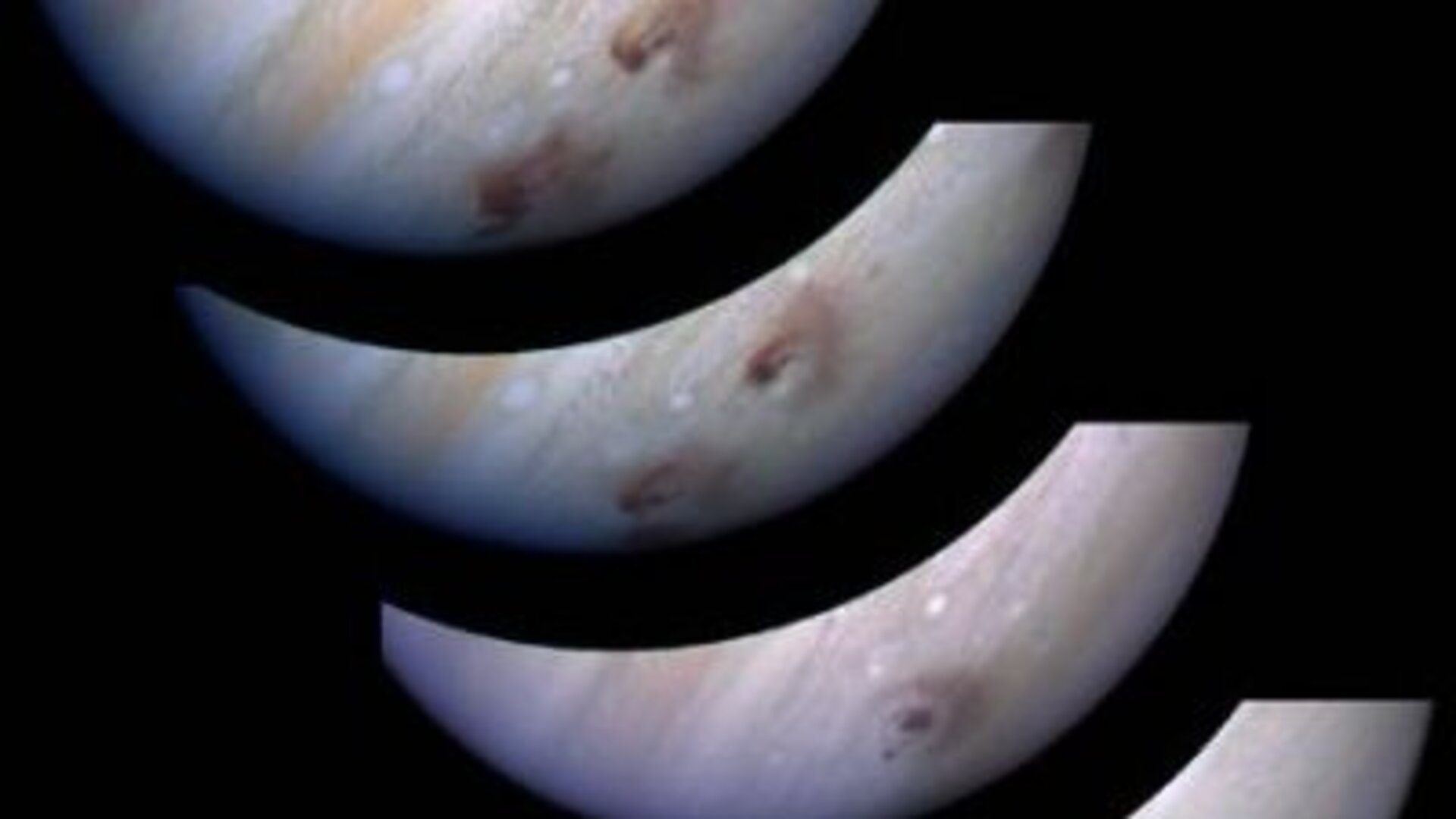

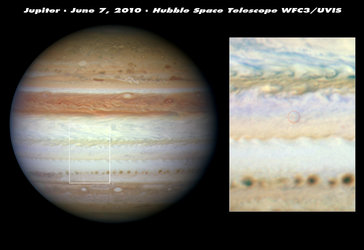

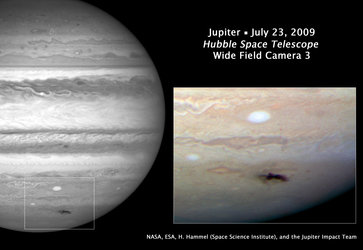

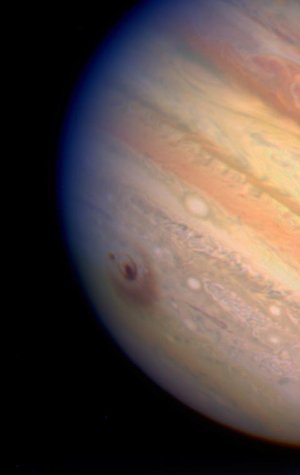

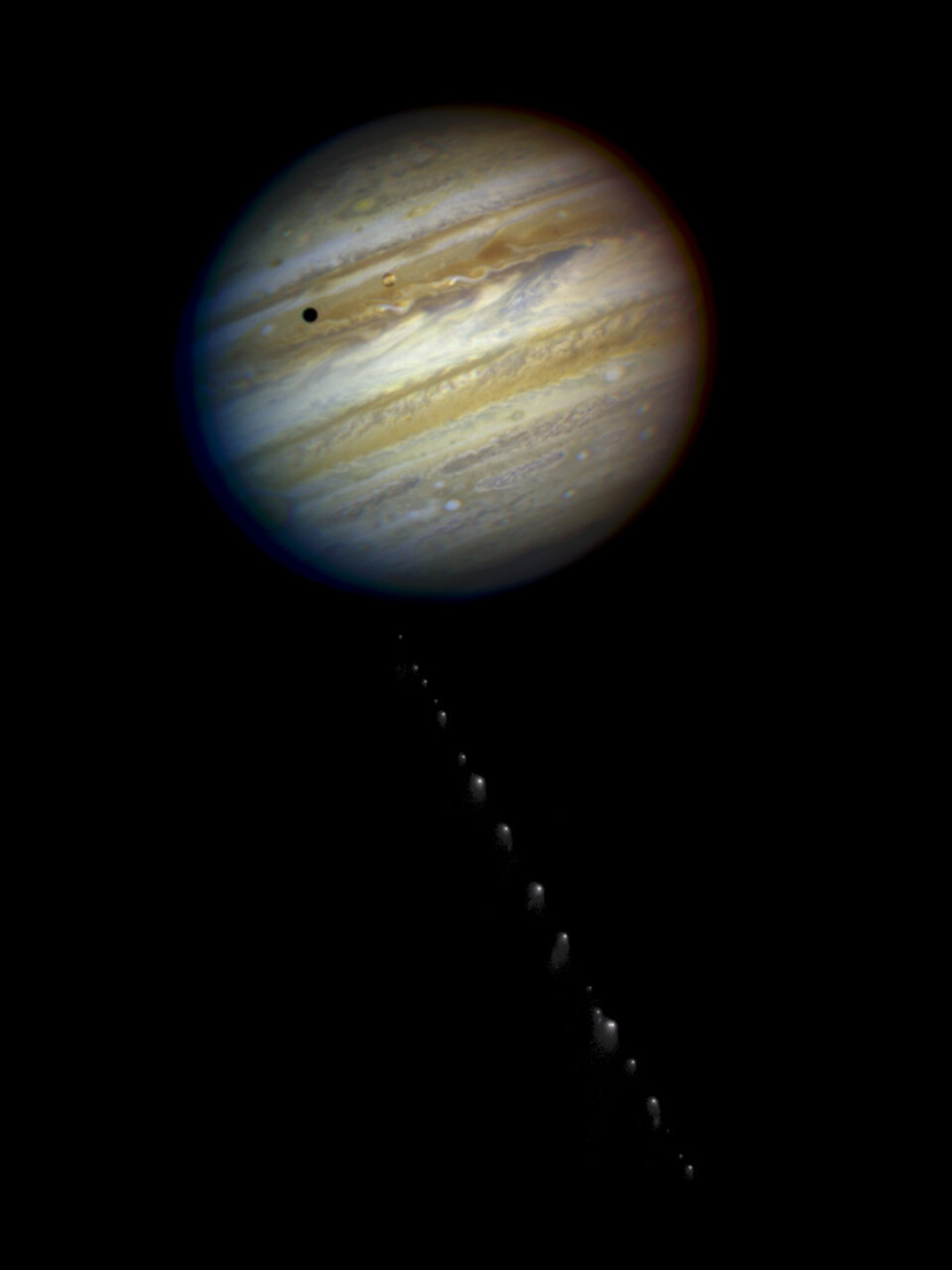

During the spectacular week-long collision, a string of 21 comet fragments pounded into the southern hemisphere of Jupiter, leaving dark scars in the planet’s atmosphere that persisted for several weeks.

The remarkable event was the first direct observation of an extraterrestrial collision in the Solar System. It was followed worldwide by amateur and professional astronomers with many ground-based telescopes and the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope.

ESA’s Infrared Space Observatory was launched in 1995 and was the first to detect and study water in Jupiter’s upper atmosphere. It was widely speculated that comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 may have been the origin of this water, but direct proof was missing.

Scientists were able to exclude an internal source, such as water rising from deeper within the planet’s atmosphere, because it is not possible for water vapour to pass through the ‘cold trap’ that separates the stratosphere from the visible cloud deck in the troposphere below.

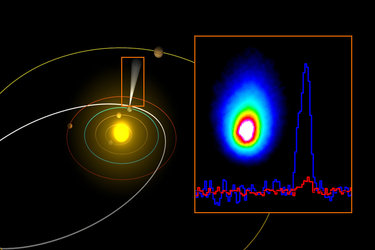

Thus the water in Jupiter’s stratosphere must have been delivered from outside. But determining its origin had to wait more than 15 years, until Herschel used its sensitive infrared eyes to map the vertical and horizontal distribution of water’s chemical signature.

Herschel’s observations found that there was 2–3 times more water in the southern hemisphere of Jupiter than in the northern hemisphere, with most of it concentrated around the sites of the 1994 comet impact. Additionally, it is only found at high altitudes.

“Only Herschel was able to provide the sensitive spectral imaging needed to find the missing link between Jupiter’s water and the 1994 impact of comet Shoemaker-Levy 9,” says Thibault Cavalié of the Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Bordeaux, lead author of the paper published in Astronomy and Astrophysics.

“According to our models, as much as 95% of the water in the stratosphere is due to the comet impact.”

Another possible source of water would be a steady rain of small interplanetary dust particles onto Jupiter. But, in this case, the water should be uniformly distributed across the whole planet and should have filtered down to lower altitudes.

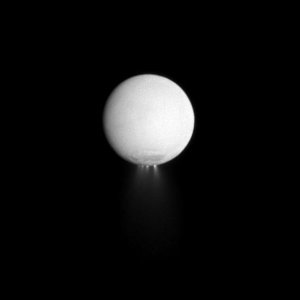

Also, one of Jupiter’s icy moons could deliver water to the planet via a giant vapour torus, as Herschel has seen from Saturn’s moon Enceladus, but this too has been ruled out. None of Jupiter’s large moons is in the right place to deliver water to the locations observed.

Continue reading below

Finally, the scientists were able to rule out any significant contributions from recent small impacts spotted by amateur astronomers in 2009 and 2010, along with local variations in the temperature of Jupiter’s atmosphere.

Shoemaker-Levy 9 is the only likely culprit.

“All four giant planets in the outer Solar System have water in their atmospheres, but there may be four different scenarios for how they got it,” says Dr Cavalié. “For Jupiter, it is clear that Shoemaker-Levy 9 is by far the dominant source, even if other external sources may contribute also.”

“Thanks to Herschel’s observations, we have now linked a unique comet impact – one that was followed in real time and which captured the public’s imagination – to Jupiter’s water, finally solving a mystery that has been open for nearly two decades,” adds Göran Pilbratt, ESA’s Herschel project scientist.

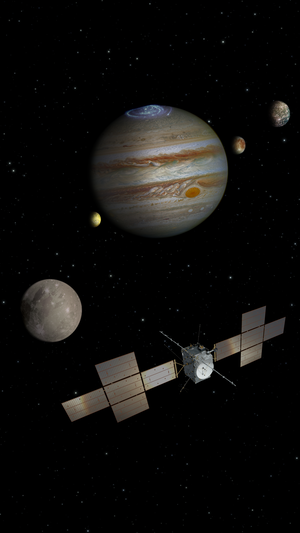

The observations made in this study foreshadow those planned for ESA’s future Jupiter Icy moons Explorer mission launching towards the Jovian system in 2022, where it will map the distribution of Jupiter’s atmospheric ingredients in even greater detail.

Notes for Editors

“The spatial distribution of water in the stratosphere of Jupiter from Herschel-HIFI and –PACS observations,” by T. Cavalié et al. is published in Astronomy & Astrophysics, 553, A21, May 2013.

The observations were obtained under the Herschel Guaranteed Time Key Programme “Water and related chemistry in the Solar System”. HIFI observations were taken in July 2010 and PACS observations were made in October 2009 and December 2010. The results were complemented with data on the stratospheric temperature of Jupiter taken at NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility taken during the same period.

Herschel is an ESA space observatory with science instruments provided by European-led Principal Investigator consortia and with important participation from NASA.

For further information, please contact:

Markus Bauer

ESA Science and Robotic Exploration Communication Officer

Tel: +31 71 565 6799

Mob: +31 61 594 3 954

Email: markus.bauer@esa.int

Thibault Cavalié

Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Bordeaux (joint research unit of the CNRS-INSU and University Bordeaux, France)

Tel: +33 5 57 77 61 24

Email: cavalie@obs.u-bordeaux1.fr

Göran Pilbratt

ESA Herschel Project Scientist

Tel: +31 71 565 3621

Email: gpilbratt@rssd.esa.int

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland