How to make the Sun transparent

On the Sun’s visible surface, waves rise and fall like a gigantic ocean swell, every five minutes or so. A special set of instruments on SOHO, provided by US-led, French-led and Swiss-led teams, have targeted these waves and so opened up the Sun’s interior to inspection.

The surface oscillations, caused by sound waves passing through the Sun, can be interpreted in much the same way as earthquake waves, which reveal the secrets of the interior of our own planet. The scientists call this science ‘helioseismology’.

Much of the headline news from SOHO during the past ten years has concerned its discoveries about what happens below the fiery surface. In this respect, the Michelson Doppler Imager, from Stanford University, has led the way.

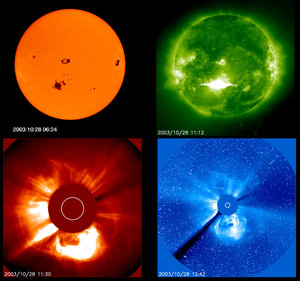

The MDI maps great flows of sub-surface currents of gas, equivalent to the deep ocean currents on Earth. It reveals how hot gas rising from the deep interior can be throttled by magnetic whirlpools to create the relatively cool dimples in the surface that we see as dark sunspots.

A heartbeat of the Sun, with currents of gas speeding up and slowing down like the blood in human arteries, showed up when scientists combined data from SOHO and a US-led network of ground stations called GONG.

They gauged the variable flows more than 200 000 kilometres beneath the surface. What took them by surprise was the ‘pulse rate’ – not, as you might expect, once in eleven years to match the magnetic cycle, but once in 16 months.

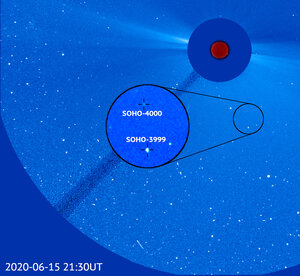

Most spectacularly, SOHO can see right through the Sun to detect sunspots on the far side. Besides depressing the Sun’s surface, their strong magnetic fields speed up the sound waves.

As a result, the scientists detect sound waves arriving sooner at the visible surface, from a group of sunspots present on the far side, than equivalent waves coming from sunspot-free regions. That’s how they make the Sun transparent.

As the Sun rotates on its axis, sunspots swing into view and associated magnetic explosions then threaten Earth’s space environment.

By detecting the sunspots when they are still hidden from view on the far side, the Stanford helioseismologists can give a few days’ advance warning of trouble ahead.

Another instrument on SOHO, the French-Finnish SWAN telescope, detects far-side storms by seeing the ultraviolet rays that they emit illuminating the hydrogen gas in space beyond the Sun, like a lighthouse beam.

For more information:

Bernhard Fleck, ESA SOHO Project Scientist

E-mail: bfleck @ esa.nascom.nasa.gov

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland