Sophisticated spacecraft

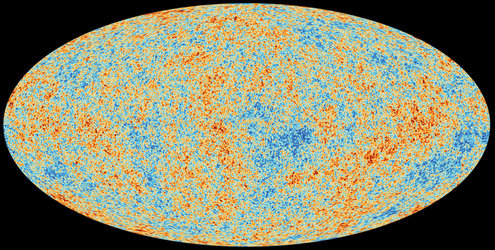

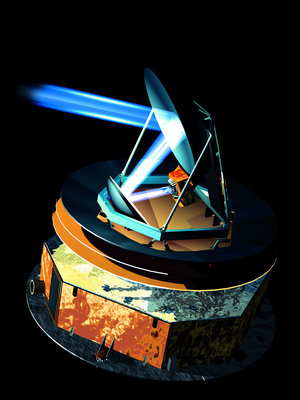

Planck studied the Cosmic Microwave Background by measuring its temperature all over the sky. Planck’s large telescope collected light from the CMB and focused it onto two arrays of radio detectors, which translated the signal into a temperature reading.

The detectors on board Planck were highly sensitive. They looked for variations in the temperature of the CMB of about a million times smaller than one degree – this is comparable to measuring from Earth the heat produced by a rabbit sitting on the Moon.

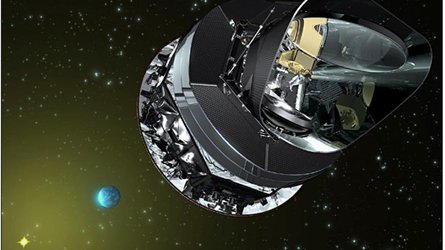

The Planck spacecraft consisted of two main elements: a warm satellite bus, or service module, and a cold payload module, which included the two scientific instruments and the telescope.

The service module had an octagonal shape. It housed the data handling systems and subsystems essential for the spacecraft to function and communicate with Earth, and the electronic and computer systems of the instruments. At the base of the service module was a flat, circular solar panel that generated power for the spacecraft and protected it from direct solar radiation.

The baffle was an important part of the payload module. It surrounded the telescope, limiting the amount of stray light incident on the reflectors. It also helped radiate excess heat into space, cooling the focal plane units of the instruments and the telescope to a stable temperature of about –223ºC (or 50 K). The baffle formed part of the passive cooling system for the satellite, which supported the active cooling system.

The solar array, located at the bottom of the service module at one end of the spacecraft, was permanently illuminated by sunlight. Three reflective thermal shields isolated the service module from the payload module at the opposite end. This prevented heat generated by the solar array and the electronic boxes inside the service module from diffusing to the payload module.

This passive cooling system brought the temperature of the telescope down to around 50 K. The temperature of the detectors was further decreased to levels as low as 0.1 K by a three-stage active refrigeration chain. The resulting difference in temperature between the warm and cold ends of the satellite was an astounding 300 K.

The coldest detectors

A key requirement was that Planck’s detectors must be cooled to temperatures close to the coldest temperature reachable in the Universe – absolute zero – which is –273.15°C, or, expressed in the scale used by scientists, zero Kelvin (0 K).

At the time of its release, only about 380 000 years after the Big Bang, what we detect as the CMB today had a temperature of some 3000 K; but now, with the expansion and cooling of the Universe, the temperature of this radiation appears to be just 2.7 K (about –270ºC).

The detectors on board Planck had to be very cold so that their own heat did not swamp the signal from the sky. All of them were cooled to temperatures below –253ºC, and some of them reached the amazingly low temperature of just one-tenth of a degree above absolute zero. These detectors were the coldest known points in space.

Sharp vision

With its unprecedented angular resolution, Planck provided the most accurate measurements of the CMB yet.

The angular resolution is a measure of Planck's sharpness of vision, i.e. the smallest separation between regions in the sky that the detectors were able to distinguish; the smaller the separation, the sharper (better) the information gathered. Planck's sharpness of vision was such that it could distinguish objects in the sky with a much higher resolution than any other space-based mission that has studied the CMB.

Planck's detectors had the ability to detect signals 10 times fainter than its most recent predecessor, NASA's WMAP, and its wavelength coverage allowed it to examine wavelengths 10 times smaller. In addition, the telescope’s angular resolution was three times better. The resulting effect was that Planck was able to extract 15 times more information from the CMB than WMAP.

With its sharp vision and high sensitivity, Planck's data is enabling scientists to extract all the information that the fluctuations in the CMB hold.

Broad wavelength coverage

The Planck detectors were specifically designed to detect microwaves at nine wavelength bands from the radio to the far-infrared, in the range of a third of a millimetre to one centimetre. This includes wavelengths that had not been observed before. The wide coverage was required in order to face a key challenge of the mission: to differentiate between useful scientific data and the many other undesired signals that introduce spurious noise.

The problem is that many other objects, such as our own galaxy, emit radiation at the same wavelengths as the CMB itself. These confusing signals had to be monitored and removed from the measurements; Planck used several of its wavelength channels to measure signals other than the CMB, thus obtaining the cleanest signal of the CMB ever.

In addition, as it was monitoring signals other than the CMB, Planck gathered data on celestial objects including star fields, nebulae and galaxies in the microwave range with unprecedented accuracy, providing scientists with the best astrophysical observatory ever in these wavelengths.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland