The magic of ion engines

Operating in the near vacuum of space, ion engines shoot out a propellant gas much faster than the jet of a chemical rocket. They deliver about ten times as much thrust per kilo of propellant used. The ions that give the engines their name are charged atoms, accelerated by a choice of electric guns. If the power comes from the spacecraft's solar panels, the technique is called 'solar-electric propulsion'.

Ion engines work their magic in a leisurely way. As solar panels of a normal size supply only a few kilowatts of power, a solar-powered ion engine cannot compete with the whoosh of a chemical rocket. But a typical chemical rocket burns for only a few minutes. An ion engine can go on pushing gently for months or even years - for as long as the Sun shines and the small supply of propellant lasts.

In 1998, NASA launched a demonstration spacecraft called Deep Space 1, which flew by a near-Earth asteroid and went on to intercept a comet. ESA's SMART-1, with much less chemical boost, went only as far as the Moon. But it served to demonstrate more subtle operations of the kind needed in distant missions. These will combine solar-electric propulsion with manoeuvres using the gravity of planets and moons.

By Sun power towards the Sun

SMART-1 helped ensure Europe's competence in the use of electric propulsion, and its independence in the 21st century space technology of the 21st Century.

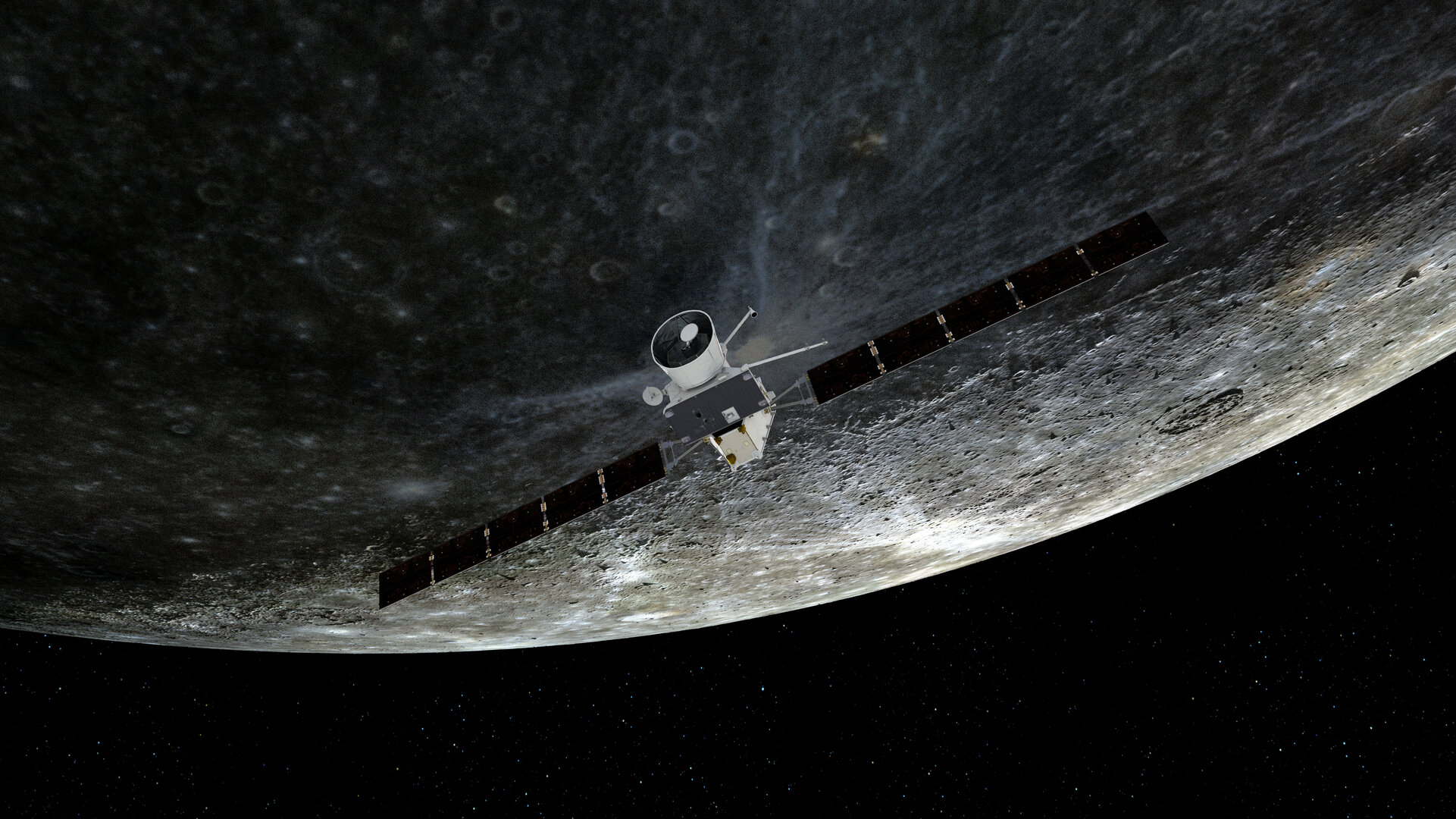

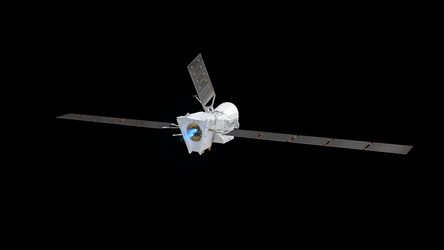

BepiColombo, ESA's mission to the innermost planet Mercury, near to the Sun, is using ion engines to speed it on its way.

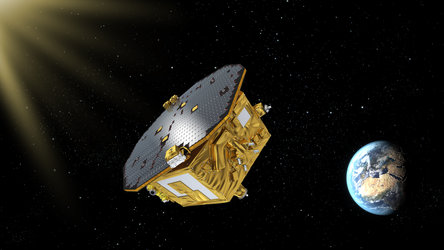

Other space science missions are expected to use ion engines for complex manoeuvres in the vicinity of the Earth's orbit, including LISA, a mission that which will detect gravitational waves coming from the distant Universe.