Solar Orbiter overview

Status

Operational

Objective

To perform close-up, high-resolution studies of our Sun and inner heliosphere, Solar Orbiter is intended to brave the fierce heat and carry its telescopes to just one-quarter of Earth's distance from our nearest star.

Mission

ESA’s Solar Orbiter mission is conceived to perform a close-up study of our Sun and inner heliosphere - the uncharted innermost regions of our Solar System - to better understand, and even predict, the unruly behaviour of the star on which our lives depend. At its closest point, the spacecraft will be within the orbit of Mercury, braving the fierce heat to provide unique data and imagery of the Sun.

Solar Orbiter will be the first satellite to provide close-up views of the Sun's polar regions, which are very difficult to see from Earth, providing images from high latitudes. It will also be able to see solar storms building up over an extended period from the same viewpoint, delivering data of parts of the Sun not visible from Earth.

Objectives

With a combination of in-situ and remote-sensing instruments Solar Orbiter will address the central question of heliophysics: How does the Sun create and control the heliosphere? This primary, overarching scientific objective can be expanded into four interrelated top-level scientific questions that will be addressed by Solar Orbiter:

- What drives the solar wind and where does the coronal magnetic field originate from?

- How do solar transients drive heliospheric variability?

- How do solar eruptions produce energetic particle radiation that fills the heliosphere?

- How does the solar dynamo work and drive connections between the Sun and the heliosphere?

What's special?

At nearly one-quarter of Earth's distance from the Sun, Solar Orbiter will be exposed to sunlight 13 times more intense than what we feel on Earth. The spacecraft must also endure powerful bursts of atomic particles from explosions in the solar atmosphere.

To withstand the harsh environment and extreme temperatures, Solar Orbiter must be well equipped. It will exploit new technologies being developed by ESA for the mission BepiColombo to Mercury, the planet closest to the Sun. This includes high-temperature solar arrays and a high-temperature high-gain antenna.

The close-up pictures of weird solar landscapes, where glowing gas dances and forms loops in the strong magnetic field, will be stunning. They will show 180 km-wide details, (the width of the Sun's visible disc is 1.4 million kilometres).

When travelling at its fastest along its orbit around the Sun, Solar Orbiter will be able to track the same region of the solar atmosphere for much longer than is possible from Earth. This will allow it to watch storms building up in the atmosphere over several days.

Spacecraft and instruments

Solar Orbiter is specially designed to always point to the Sun, and so, its Sun-facing side is protected by a sunshield. The spacecraft will also be kept cool by the positioning of special radiators, which will dissipate excess heat into space. The solar arrays and the communications system are inherited from the design of ESA’s BepiColombo mission to Mercury.

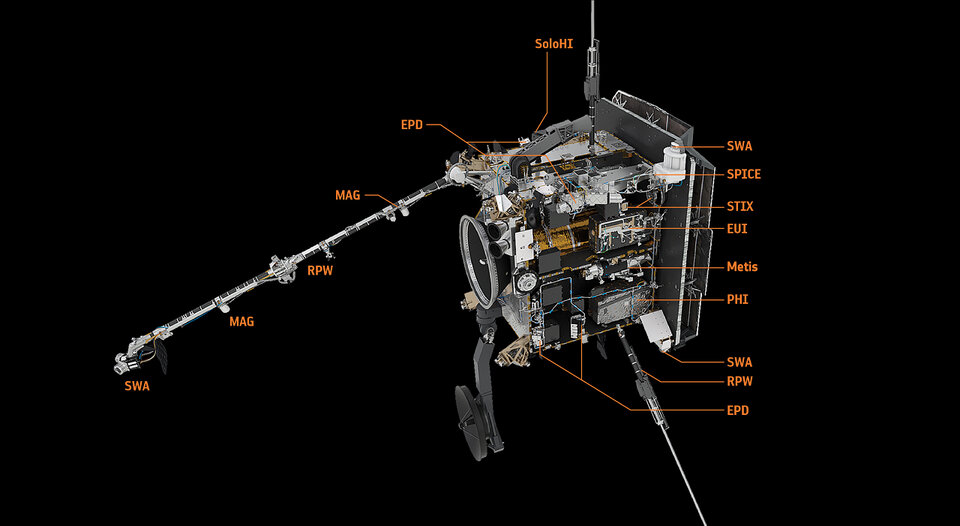

Solar Orbiter will carry a number of highly sophisticated, lightweight instruments, weighing a total of 180 kg. One suite consists of detectors meant to observe particles and events in the immediate vicinity of the spacecraft. These include the charged particles and magnetic fields of the solar wind, radio and magnetic waves in the solar wind, and energetic charged particles.

The other set of instruments will observe the Sun's surface and atmosphere. The gas of the atmosphere is best seen by its strong emission of short-wavelength ultraviolet rays. Tuned to these will be a full-Sun and high-resolution imager and a high-resolution spectrometer. The outer atmosphere will be revealed by visible-light and ultraviolet coronagraphs that blot out the bright disc of the Sun. To examine the surface by visible light, and measure local magnetic fields, Solar Orbiter will carry a high-resolution magnetograph.

Journey

Access the video

Following launch, foreseen for February 2020, Solar Orbiter will begin its journey to the Sun. This will require a cruise phase lasting less than two years. During this time, the instruments will be commissioned, and some in-situ data will be acquired. During the cruise, Solar Orbiter will use gravity assists from Venus and the Earth. These swing-bys will put Solar Orbiter into an initial 180 day-long orbit around the Sun from which the spacecraft will begin its scientific mission.

Along this orbit, the spacecraft will reach closest approach to the Sun every six months, at around 42 million km from the Sun, or about 60 solar radii.

During the course of the mission, additional Venus gravity assist manoeuvres will be used to increase the inclination of Solar Orbiter’s orbit, helping the instruments see the polar regions of the Sun clearly, for the first time. Solar Orbiter will eventually view the poles from an angle higher than 30 degrees, compared to 7 degrees at best from Earth.

The mission will be controlled from the European Space Operations Centre (ESOC), Darmstadt, Germany, using ESA’s Malargüe ground-station. Other ESTRACK stations such as New Norcia in Australia and Cebreros in Spain will act as backups.

The Science Operations will be managed from the European Space Astronomy Centre (ESAC), Madrid, Spain

History

In the past, the six European-built spacecraft of the Ulysses, SOHO, and Cluster missions have made many amazing discoveries about the Sun, and how its storms affect Earth.

In 1998, European scientists met in Tenerife and produced a report called 'A Crossroads For European Solar and Heliospheric Physics’. It took scientific ideas and concepts and by building upon the work begun by the space missions to the Sun, attempted to define how European solar physics would proceed.

One of the ideas in the report was to send a mission to take images of the Sun both in the visible and ultraviolet wavelengths. The imaging equipment would be similar to the SOHO mission, but the coverage of the Sun would be out-of-the-ecliptic, similar to Ulysses.

A second idea was to get closer to the Sun than ever before (about 30 solar radii away, 0.15 AU, half the distance from the Sun to Mercury) and obtain high spatial resolution images. In such an orbit, at perihelion (the closest point of an orbit to the Sun), a spacecraft would be located above one particular point on the Sun for a relatively long period, thus enabling a more detailed look than ever before.

In 1999, a team was set up to study the various options and concluded that these two ideas could be combined in one mission. A few technical issues were found, which meant compromises had to be made with respect to the distance of closest approach that could be achieved. By using the gravity of Venus, the mission could also, over time, change its orbit dramatically.

Following several years of assessment studies by industry and ESA, the mission now called Solar Orbiter, was selected as one of the three candidates for the first two Cosmic Vision M-class mission launch slots (nominally 2017 and 2018) in February 2010. In October 2011, Solar Orbiter and Euclid were selected as the Cosmic Vision M1 and M2 missions.

Partnerships

Solar Orbiter is managed and financed mainly by ESA, but with strong international collaboration. NASA will provide the launcher and contribute instruments to the scientific payload in the context of the International Living With a Star initiative.

Solar Orbiter will also coordinate its scientific mission with NASA's Solar Probe Plus to maximise their combined science return.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland