The solar wind

The space between the planets of the Solar System is not actually empty, but filled with a driving rain of particles constantly streaming outwards from the Sun at speeds of up to more than 2 million km an hour. The giant bubble of space filled by this ‘solar wind’ is called the heliosphere and it reaches out to around three times the distance to Pluto.

The particles in the solar wind are mostly electrons, protons and alpha radiation, but there are also trace amounts of heavy ions and atomic nuclei including carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and some heavier metals. Because the solar wind contains so many electrically charged particles, it carries with it some of the Sun’s magnetic field.

The charged particles rain down on Earth constantly, but the intensity of the rain depends on solar activity. The normally steady solar wind can be interrupted by heavier showers caused by large, fast-moving bursts of energetic particles from the Sun called coronal mass ejections (CMEs), or solar storms. Solar storms change the environmental conditions in space and produce what is known as space weather.

Access the video

Luckily, Earth is holding up a massive umbrella against this driving rain. A magnetic field bubble called the magnetosphere deflects most of the charged particles in the solar wind around Earth and keeps us safe from their harmful effects. But just like our feet might get wet under heavy rain even when we carry a good umbrella, when the solar wind is strong enough some particles make it through our magnetosphere. The visible result is the beautiful northern and southern lights. But the invisible harmful impact on our technological systems could be huge.

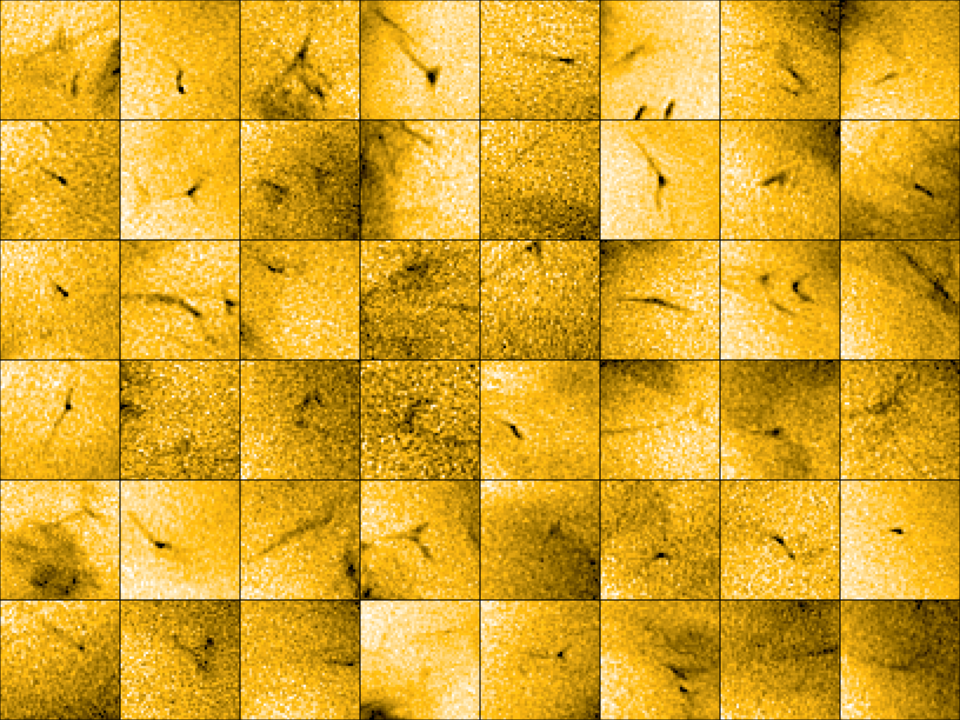

ESA’s Solar Orbiter mission is already taking the closest ever images of the Sun to observe the origin of the solar wind (and other phenomena) like never before. In 2023, the mission discovered tiny jets that power the solar wind.

Understanding better where the solar wind comes from is very important, but it’s also important to improve our knowledge of how exactly it affects Earth; this is where ESA’s Solar wind-Magnetosphere-Ionosphere Link Explorer (Smile) mission comes in.

Smile will investigate how the solar wind behaves when it meets Earth’s magnetic field. The mission will consider how, when and where energy and charged particles from the solar wind enter the magnetosphere. It will help us understand how and why space weather threats arise – including the more gentle daily substorms, as well as the rarer violent geomagnetic storms that are driven by solar storms.

Ultimately, the mission will help us forecast all types of space weather in advance. Here on Earth, predicting extreme weather like hurricanes is crucial for public safety, but on a day-to-day basis people are more interested in whether it’s going to rain during their commute. It’s similar for space weather: it’s vital that we can predict the catastrophic events in advance, but these are rare. On a day-to-day basis, it is important to predict the less extreme space weather that can slowly but steadily damage satellites, harm astronauts in space, degrade power stations, and corrode pipelines and railway lines.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland