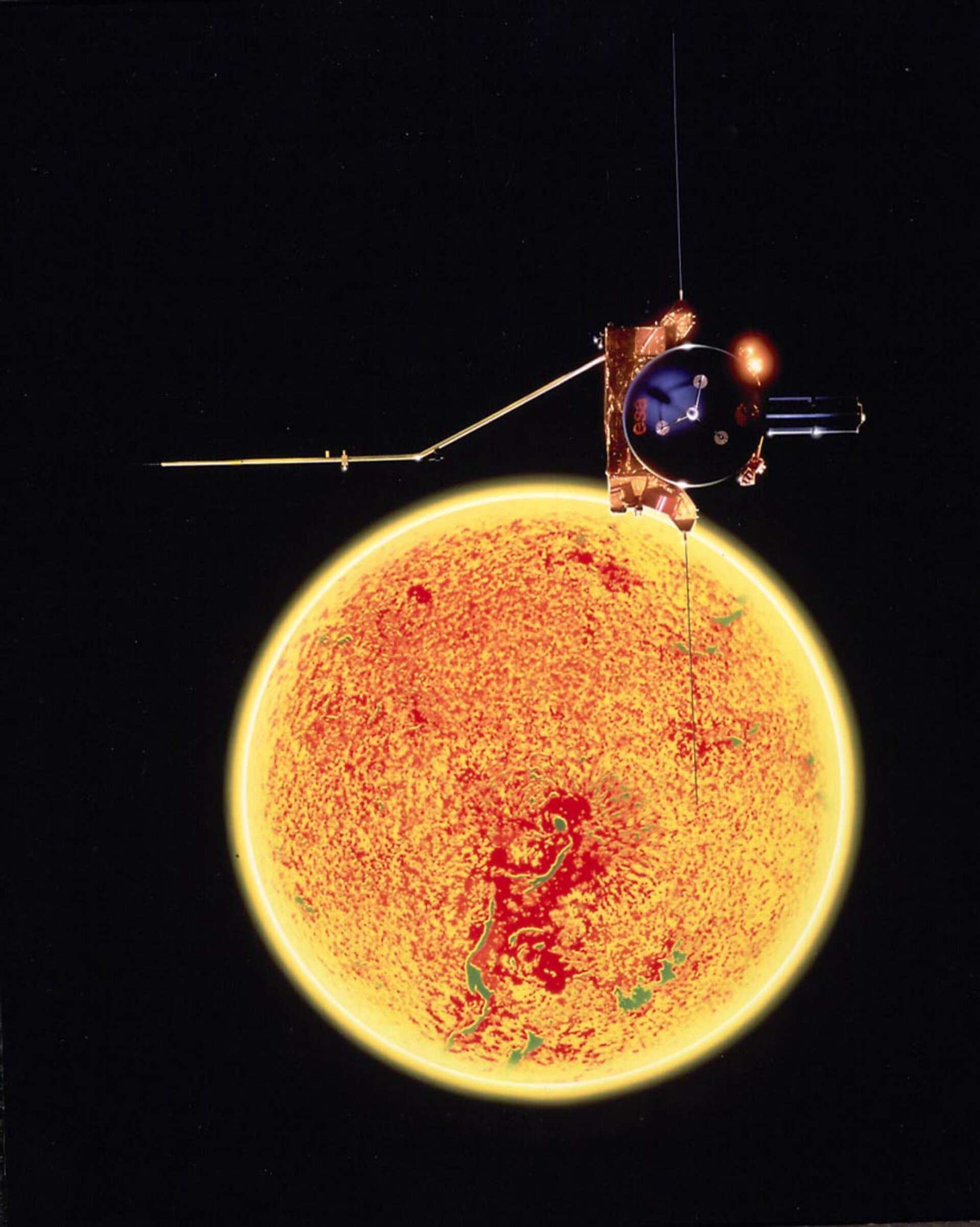

Ulysses at the North Pole

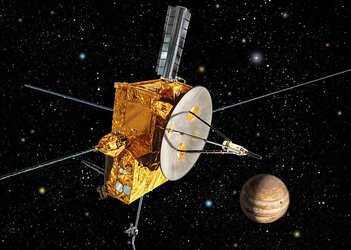

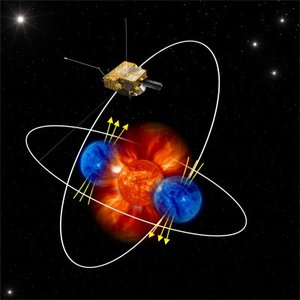

On 14 January, almost a year after visiting the south solar pole, the Ulysses spacecraft reached the highest point of its orbit over the Sun’s northern polar cap. With this, Ulysses completed its third rapid south-to-north transit to date.

“This important milestone for the joint ESA-NASA mission also coincides with the start of a new cycle of solar activity”, explains Richard Marsden, ESA’s Ulysses Mission Manager. “It’s been calm on the space weather front recently and so we are looking forward to some solar fireworks over the coming months as the number of sunspots increases.”

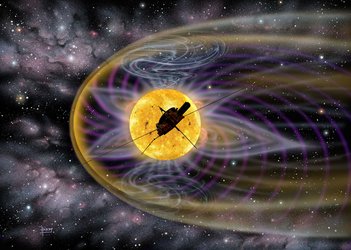

As part of an impressive fleet of interplanetary spacecraft that includes the twin STEREO probes launched by NASA in 2006 and ESA’s SOHO observatory, Ulysses is ideally placed to provide a unique perspective as our star gears up for the next peak in its activity cycle. This is expected to occur around 2012.

Although the Sun has been relatively quiet during the past year, this has not meant that the spacecraft operations team has been able to sit back and relax. On the contrary, the rapid transit from south to north through perihelion is one of the most nerve-racking periods in the 6.2-year orbit of Ulysses, now in its 18th year of operations. This is because the spacecraft experiences a dynamic disturbance as it comes closer to the Sun, causing the spinning probe to wobble, a motion called ‘nutation’.

“We have to keep the nutation under control”, says Marsden, “otherwise we could lose contact with the spacecraft. Fortunately, the operations team has developed a robust strategy to tackle this problem, and there haven’t been too many scary moments this time around!” In fact, this strategy is so effective that the scientific measurements have hardly been affected. Nutation is expected to die away over the next few weeks as Ulysses once again heads away from the Sun.

A long-standing scientific puzzle that has been under investigation during the recent south-to-north transit is the clear north-south asymmetry in the structure of the heliosphere that was found when Ulysses visited the polar caps for the first time in 1994-95, also near solar minimum. At that time, the magnetic equator separating positive and negative magnetic fields was pushed 10 degrees southward with respect to the Sun’s rotational equator.

The reason for the offset is still not fully understood, and preliminary indications are that the recent data show much less of an effect than previously. However, further study is needed before firm conclusions can be drawn, as the Ulysses measurements are not conducted in each hemisphere simultaneously and temporal changes cannot be ruled out. Nevertheless, investigations of this kind demonstrate the value of long-term out-of-ecliptic observations that only Ulysses can supply.

For more information:

Richard Marsden, ESA Ulysses Mission Manager

Email: Richard.Marsden @ esa.int

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland