Tribute to the cryptic planet

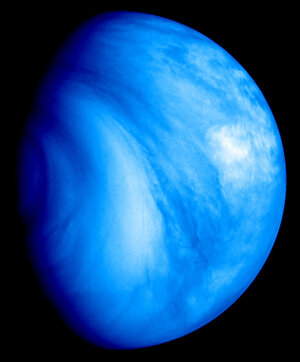

Venus, the ‘Morning Star’, the second closest planet to the Sun after Mercury and our closest planetary neighbour, has fascinated humankind from the earliest times. Named after the Roman goddess of love and beauty, it is the third brightest object in the sky after the Sun and Moon.

Since the beginning of the space era, Venus has been an attractive subject for planetary science and it was one of the first natural targets to explore, due to its vicinity to Earth – twice as close to Earth as Mars at the closest approach point.

An entirely different, exotic and inhospitable world

Very similar to Earth in size and mass, Venus was expected to be very similar to our planet when the first Russian and American space probes approached it in the early 1960s and started returning the first data about its atmosphere.

Observers soon realised that Venus is an entirely different, exotic and inhospitable world, hidden behind a curtain of dense clouds of noxious gases. It has an atmosphere mainly composed of carbon dioxide, with crushing surface pressure and burning-hot temperatures.

Then the question arose: why did a planet apparently so similar to Earth evolve in a way so radically different over the last four thousand million years?

Many missions were lost, many landers were destroyed.

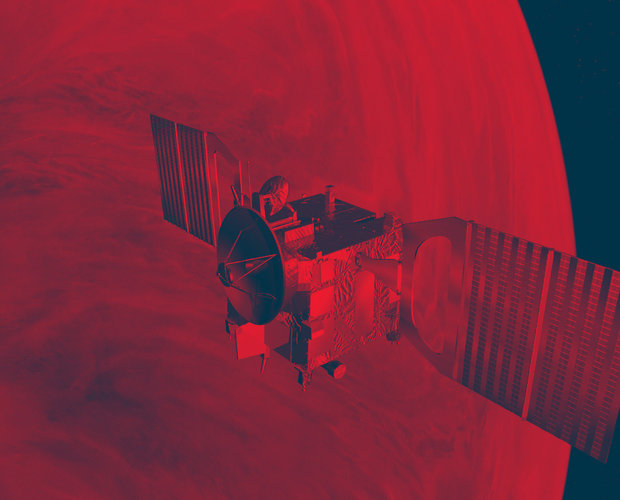

Up to the mid 1990s, many ground observatories and more than 20 spacecraft had attempted to explore Venus. A set of orbiters and descent probes - the Soviet Venera series and the Vega balloons and landers, the US Mariner, Pioneer Venus and the Magellan missions - tried to penetrate this hostile world to add pieces to the big puzzle that Venus represented for scientists.

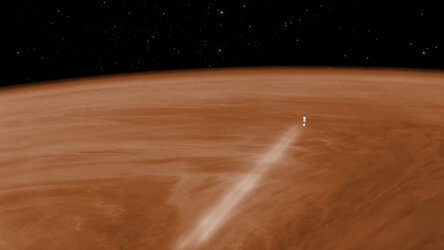

Many missions were lost, many landers were destroyed under the high pressure and temperature of the Venusian atmosphere while providing the first information about the planet. It is still due to such a dense atmosphere with thick cloud cover that, for years, scientists were prevented from seeing what lays below and from understanding the nature of the Venusian surface.

Only when modern radar imaging systems became operational on space probes and ground observatories, did the first glimpses of the real face of Venus started to emerge.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland