Science with Webb

Webb’s science goals cover a very broad range of themes, and will tackle many open questions in astronomy. They can be divided into four main areas:

Other worlds

Key questions: Where and how do planetary systems form and evolve?

Thanks to the rapidly evolving field of exoplanet studies – planets beyond our Solar System – Webb will be able to contribute to key questions such as: is Earth unique? Do other planetary systems similar to ours exist? Are we alone in the Universe?

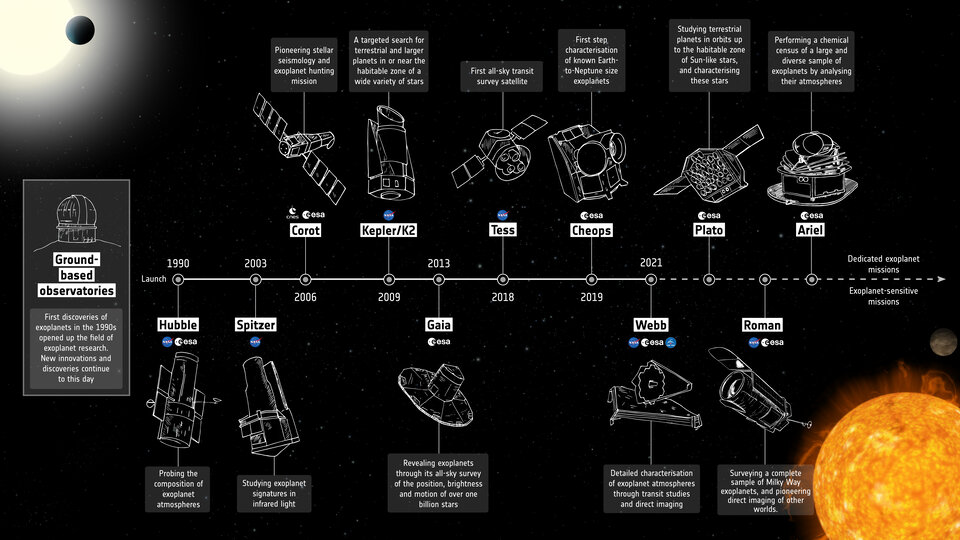

Webb will study in detail the atmospheres of a wide diversity of exoplanets. It will search for atmospheres similar to Earth’s, and for the signatures of key substances such as methane, water, oxygen, carbon dioxide, and complex organic molecules, in the exciting hope of finding the building blocks of life. In this way, Webb will complement ESA’s Atmospheric Remote-sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large-survey (Ariel), a space telescope that will study what exoplanets are made of, how they formed and how they evolve.

Closer to home, Webb will also study the outer planets in our own Solar System. Many exoplanets resemble Neptune and Uranus, thus studying planets in our own solar neighbourhood can provide new insights for better understanding planetary formation in general.

The lifecycle of stars

Key questions: How and where do stars form? What determines how many of them form and their individual masses? How do stars die and how does their death impact the surrounding medium?

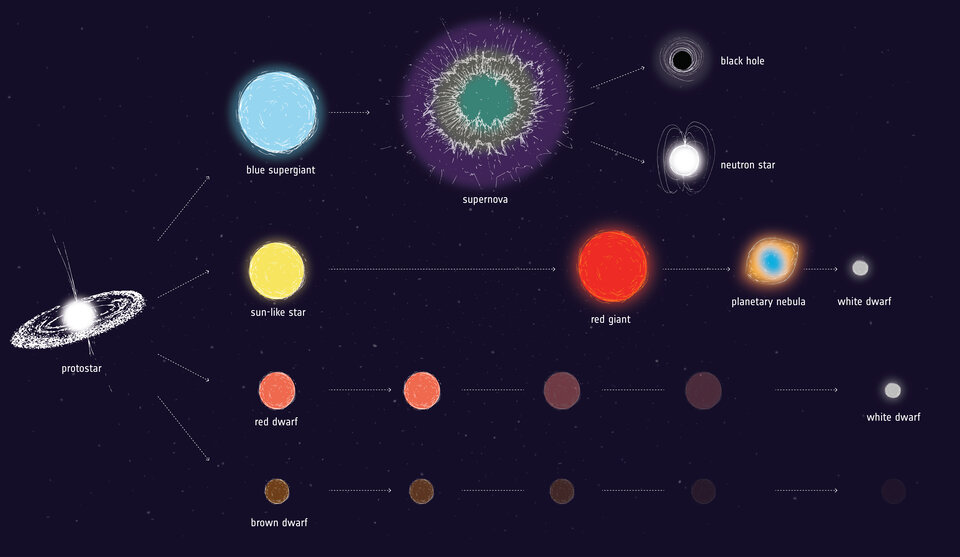

Stars transform the Universe’s simple elements into heavier elements and, through supernova explosions, spread them throughout the cosmos. Observing in the infrared part of the spectrum, Webb will be capable of peering through the dusty envelopes around new-born stars. Its superb sensitivity will also allow astronomers to directly investigate faint protostellar cores — the earliest stages of star birth.

Webb will study brown dwarfs, dim objects with masses in between those of a planet and a star that are not themselves massive enough to start thermonuclear reactions and become fully fledged stars. Webb will determine how and why clouds of dust and gas collapse into stars, or become gas giant planets or brown dwarfs.

Webb will also see the most massive stars explode as supernovae and leave behind more clouds of dust and gas, along with the precious heavy metals that enrich the cosmos to form new generations of stars.

The early Universe

Key questions: What did the early Universe look like? When did the first stars and galaxies emerge?

For the first time in human history we have the opportunity to directly observe the first stars and galaxies forming. Webb’s infrared vision makes it a powerful time machine that will peer back over 13.5 billion years, pushing beyond the limits of Hubble’s “deep fields” that showed us young galaxies when they were only few hundred million years old and were small, compact, and irregular. Webb’s infrared sensitivity will not only look back further in time but will also reveal dramatically more information about stars and galaxies in the early Universe. While Hubble looked at ‘toddler’ galaxies, Webb will see the ‘baby’ phase!

Webb’s data will also answer the compelling questions of how black holes formed and grew early on, and what influence they had on the formation and evolution of the early Universe.

Galaxies over time

Key questions: How did the first galaxies evolve over time? What can we learn about dark matter and dark energy?

Today’s Universe is populated by galaxies – cosmic islands made of hundreds of billions of stars. Their sizes and shapes are vastly different, holding clues to how they formed and evolved. In the first few billion years, the Universe was very dynamic, with galaxies undergoing merging events or being ripped apart, and were peppered by supernova explosions from short-lived, massive stars. Operating at infrared wavelengths, Webb can observe the bulk of the light from these primordial galaxies and reveal their dust-shrouded star birth and matter-absorbing black holes.

Webb will also shed light on dark matter, the material that fills the cosmos but is not directly visible. In this way, Webb will complement ESA’s Euclid mission that will map the geometry of the Universe and is specifically designed to study dark energy, the force behind the Universe's accelerating expansion, and dark matter.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland