X-raying the beating heart of a newborn star

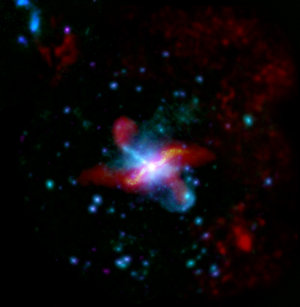

The violent behaviour of a young Sun-like star spinning at high speed and spewing out super-hot plasma has been revealed thanks to the combined X-ray vision of three space telescopes, including ESA’s XMM-Newton.

Credits: ESA - C. Carreau

Along with data from NASA’s Chandra and Japan’s Suzaku, the findings shed new light on one of the most fundamental issues in astronomy: the birth of stars like our own Sun.

Such stars form from clouds of gas and dust. These collapse under gravity and develop a dense protostar at their centre, surrounded by an orbiting disc of gas and dust.

The protostar continues to grow as material in the disc works its way towards the centre and falls onto the newborn star at speeds of up to a few hundred kilometres per second.

However, rather than falling onto the protostar, a small fraction of the material is ejected in the form of high-speed jets emanating from the north and south poles of the star.

These jets can be highly variable, pointing to energetic activity in the innermost regions.

But the thick gas and dust envelope surrounding the central star makes it hard to see what is going on.

X-rays can penetrate this dense, obscuring region, and by monitoring variations in the intensity of X-ray emission for the young Sun-like star V1647 Ori, astronomers have been able to deduce what might be happening behind the dusty disc cloaking the star.

The star resides 1300 light-years away in McNeil’s Nebula and was observed with XMM-Newton, Chandra, and Suzaku during two multi-year outbursts. The first lasted from 2003 to 2006; the second has been under way since 2008.

During these extended outbursts the star displays faster growth in mass, a surge in X-ray emission and a dramatic increase in temperature to 50 million degrees celsius.

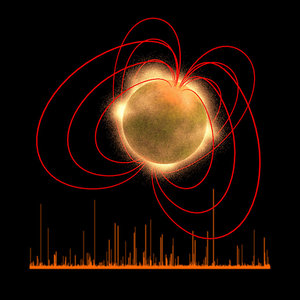

“We think that magnetic activity on or around the stellar surface creates the super-hot plasma,” says Kenji Hamaguchi, lead author of the paper published in the Astrophysical Journal.

“This behaviour could be sustained by the continual twisting, breaking, and reconnection of magnetic fields, which connect the star and the disc, but which rotate at different speeds.

“Magnetic activity on the stellar surface could also be caused by accretion of material onto it.”

In addition, another variation in X-ray emission was found to repeat regularly, with a period around just one day.

For a star of V1647 Ori’s size, this implies that it is spinning as fast as it can without ripping itself to pieces.

At the same time, matter falls onto the star in large pancake-shaped hotspots on opposite sides of the stellar surface.

“We think the super-hot plasma is located on the surface of the star, which rotates with a one day period,” says Dr Hamaguchi.

“The rising and falling in flux that we see would probably be due to the emergence and disappearance of the bright hot spot in our line of sight.”

Yet the regular heartbeat of X-ray emission seen at various times between 2004 to the present day suggest that despite the chaotic behavior, the large-scale configuration of the star–disc system remains stable over timescales of several years.

“These observations of V1647 Ori by this trio of X-ray satellites provide new insight into what might be happening inside the dusty discs of newly-forming stars,” said Norbert Schartel, ESA’s Project Scientist for XMM-Newton.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland