Will DART make its target asteroid go wobbly? Hera will see

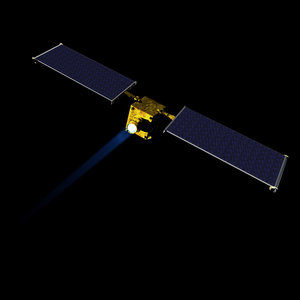

There are models and simulations, but nobody knows exactly what is going to happen after NASA’s DART impactor crashes into the smaller of the two Didymos asteroids at 6.6 km/s – humankind’s first full-scale deflection test for planetary defence.

It will take detailed telescope and radar observations from Earth to find out, complemented by a close-up survey to be performed by ESA’s Hera mission.

The collision itself takes place in late 2022. Meanwhile, PhD student Harrison Agrusa from the University of Maryland – as part of a larger team studying the dynamics of the Didymos system – is among the most qualified people to make an educated guess.

Harrison has been simulating the interaction between the fridge-sized DART spacecraft and smaller 160-m diameter Didymos asteroid hundreds of times, run on his university’s powerful computing cluster.

His simulations recreate the 780-m diameter main Didymos asteroid and its orbiting ‘Didymoon’ as a collection of small spheres – like the rubble piles that researchers believe these bodies to resemble – then apply the equivalent force of the DART impact.

“The interesting thing, depending on where DART hits and how hard, is that we can see a pronounced wobble triggered as a result,” explains Harrison.

“We’ve compared four different simulation codes to study this post-impact swinging back and forth and seen the same effect recur in all of them, even with conservative estimates of DART’s momentum transfer.”

In asteroid researcher terms this effect is known as ‘libration’ – the same term used for the wobble of the Moon as seen from Earth, which means that different parts of the lunar surface can be observed over time.

Access the video

Like the Moon, the smaller ‘Didymoon’ is expected to be tidally locked to its parent at the present time, although it has not yet been confirmed with ground-based observations. Long-range measurements of distant lightcurves – gradual patterns of light shifting over time – or radar imagery do not give enough detail.

In the same way, any wobble imparted to the asteroid by DART’s collision will not be visible from Earth. It will take close-up observations after Hera’s arrival to be sure.

Harrison has shown that this induced libration is closely related to the momentum transfer efficiency – in other words, Hera’s measuring of the libration can be used to constrain the asteroid’s deflection. Such a measurement is crucial to developing a usable, repeatable planetary defence technique.

In addition, Harrison notes that the ability to measure any libration in the post-impact asteroid will also open up a valuable scientific opportunity: “The fundamental frequency of the libration will depend on the mass of the secondary, and how that mass is distributed throughout its interior – in the same way that the frequency of a pendulum's swing depends on its mass.

“So measuring this effect will give researchers an important insight into the nature of Didymoon’s interior, constraining our models. However, it is essential to have a spacecraft on location to make such a measurement.”

Harrison is part of the DART Dynamics Working Group, led by his PhD adviser Prof. Derek Richardson, tasked with performing dynamic modelling of the Didymos system before and after DART’s impact.

“As an undergraduate I interned at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in northern California, where I encountered some researchers working on planetary defence,” explains Harrison. “I never even knew this was a field until then, but after that I decided I wanted to get involved.”

This summer Harrison returns to LLNL, where he will take advantage of their supercomputer facilities to perform full-scale impact simulations, modelling the ejecta material thrown off of the asteroid by the DART impact.

“Overall, it’s great timing for me,” says Harrison. “When the DART mission ends with its impact in 2022, then my PhD does too. We’ll get a first glimpse of the actual shape of Didymoon from DART and the LICIA CubeSat – provided by ASI, the Italian Space Agency – it will deploy before colliding. Then, within a few years Hera will be providing its data, so we can rigorously compare our models to reality.”

The Hera mission will be presented to ESA’s Space19+ meeting this November, where Europe’s space ministers will take a final decision on flying the mission.

Access the video

Each year on 30 June, the worldwide UN-sanctioned Asteroid Day takes place to raise awareness about asteroids and what can be done to protect Earth from possible impact. The day falls on the anniversary of the Tunguska event that took place on 30 June 1908, the most harmful known asteroid related event in recent history. Follow the 48-hour Asteroid Day broadcast from https://asteroidday.org/ this weekend, and join the conversation online via #AsteroidDay2019

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland