Brewster Shaw: Pilot, STS-9/Spacelab-1

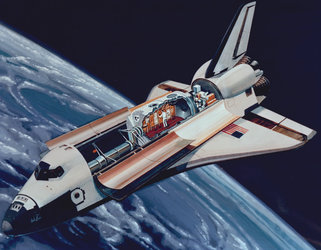

NASA astronaut Col. Brewster H. Shaw was pilot on the STS-9/Spacelab-1 mission, November 1983

Col. Brewster H. Shaw Jr was selected as a NASA astronaut in 1978. During his career, Shaw served as combat fighter pilot, test pilot and Space Shuttle astronaut and programme manager. His first spaceflight was as pilot of STS-9. He was commander of STS-61B in 1985 and STS-28 in 1989. Shaw has logged 533 hours of spaceflight and more than 5000 hours flying time in over 30 types of aircraft.

Extracts from interview by K. Rusnak, 2002, JSC Oral History

John (Young) and Owen (Garriott) were the only two guys who had flown before. Bob Parker had never flown. I’d never flown, and Ulf (Merbold) and Byron (Lichtenberg) had never flown. So John and Owen were the experienced guys, and they kind of were the mentors of the rest of us.

It was fun to watch Owen back in the module, because you could tell right from the beginning he’d been in space before, because he knew exactly how to handle himself, how to keep himself still, how to move without banging all around the other place. And the rest of us, besides he and John, the rest of us were bouncing off the walls until we figured out how to operate. But Owen, it was just like, man, he was here yesterday, you know, and it really had been years and years.

So Owen was the leader from the mission specialist standpoint, and John, of course, from the overall mission standpoint, was the leader and the person that everybody listened to and looked to. But I enjoyed working with all those guys. They’re all very smart guys, and they’d been training for three or four or five years on these experiments (John and I had only been on the flight, I guess, around a year before we flew).

It was a great experience, STS-9. This was the first time we worked twenty-four hours, two shifts, so we divided up one pilot and two scientists on each shift, and you were on duty twelve hours and then you were kind of off duty for twelve hours, and we did this little hand-over. Since there was only one of us awake on the flight deck, one of us pilot types, you didn’t want to leave the vehicle unattended very much, because this is still STS-9, fairly early in the programme. We hadn’t worked out all the bugs and everything, and neither John or I felt too comfortable leaving the flight deck unattended, so we spent most of our time there.

We had a few manoeuvres to do once in a while with the vehicle, and then the rest of the time you were monitoring systems. After a few days of that, boy, it got pretty boring, quite frankly. You spent a lot of time looking out the window and taking pictures and all that. But there was nobody to talk to, because the other guys were in the back end in the Spacelab working away, and, you know, you just had a ‘Gosh, I wish I had something to do’ kind of feeling. But the flight went fine and we did a great bunch of science.

Probably the most difficult aspect of the whole thing was after we got on orbit, we couldn’t get the hatch open, so we couldn’t get back into the Spacelab at all. I mean, I remember thinking, ‘Holy smokes. This mission’s not going to go well if we can’t get into the lab.’ [Laughs] But we finally managed to get the hatch open, but it took us a few minutes. Looking at Owen and Bob’s faces, I remember thinking, ‘Boy, these guys are seeing their lives pass in front of their face, if we can’t in there to do the stuff that they’ve been training for all these years to do.’ But we did, and it was a very successful mission.

Also on that flight was when we had the two GPCs, the two [general purpose] computers, fail, and that was an interesting thing, too. John and I were in the de-orbit prep, and he was in his seat and I was just kind of floating over the console with the checklist there reading the steps to him and we were going through, and we were reconfiguring the GPCs and the flight control systems and the reaction control system jets and stuff.

About the time that we were reconfiguring the computers, we had a couple of thruster firings, and the big jets in the front fired and it’s like these big cannons — boom! boom! — and it shocks the vehicle. So we had one of these firings and we got the big ‘X pole fail’ on the CRT, meaning the computer had failed. This is the first computer failure we had on the programme. Our eyes got about that big. So I get out the emergency procedure checklist and say, “Okay, first GPC fail. Here’s what we do.” We started going through the steps and everything. And in just a couple of minutes we had another one fail the same way, a firing of the jets and the computer failed. So now we were really interested in what was going on.

So we ended up waving off our de-orbit at that time. So the ground decided, no, we’re going to wait and try to figure out what’s going on with these computers. In the meantime, it was the end of John’s shift and John was tired, so he went down to take a nap. We had sleep stations. This was the first time we flew these sleep bunks. So John went in there and was trying to get some rest. I’m up on the flight deck. As I recall, Bob Parker came up and was with me part of the time, too, and we’re just kind of babysitting the thing.

Well, all of a sudden there starts this kind of noise, bang, bang, bang, bang, bang, bang. The next thing, one of our three IMUs [Inertial Measurement Units] fails, and we didn’t know why or anything. But, sure enough, it failed and we couldn’t recover it. It turned out its gimbal was failing and it was beating itself to death against the gimbal stop, and that was the banging noise. So after a few hours, John comes back upstairs and says, “You know, I really appreciate you guys making all that banging noise when I’m trying to sleep down there.”

You know, I said, “Jeez, John, I’ve got some bad news. Man, we lost an IMU.” And John’s eyes get this big again, because we’ve had two GPC failures and now an IMU failure. Anyhow, we got through all that and we entered and landed, and when the nose gear slapped down, one of the GPCs that had recovered failed again. One of them didn’t recover and we flew down with one less computer, but that computer failed again.

We learned a lot from that flight, a tremendous amount. I mean, we did investigations in all of the various areas of interest, from human physiology, materials processing, fluids, all kinds of stuff. Seventy-seven different investigations, as I recall, on that mission. It was a tremendous success. Learned that the human immune system isn’t as active on orbit as it is on the ground, so you shouldn’t cut yourself or you shouldn’t get sick on orbit, because you’re not going to fight it off as well. That was one of the things learned out of that flight.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland