Science in a can: Spacelab’s first flight

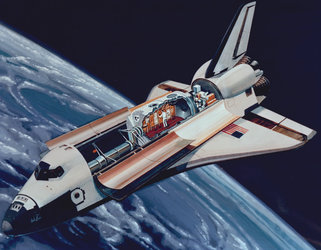

ESA’s Spacelab orbital laboratory flew for the first time on 28 November 1983 aboard the STS-9 flight of the Space Shuttle Columbia. The 15 088 kg mass of Spacelab – a 6.7 m long, 4.1 m diameter pressurised module plus external pallets – included about 3000 kg of internal and external payloads, made up of a total of 73 different experiments. This exceeded the mass of all previous payloads flown on missions by ESA and predecessor organisation ESRO put together.

Space shift work

Ulf Merbold, ESA astronaut: Spacelab-1 was the first NASA flight where the crew worked in shifts… with a Red Team and Blue Team. Everyone was on duty for about 12 hours, then we had the handover and we could go back to the Shuttle mid-deck which was our living quarters.

Spacelab-1 changed the way NASA did things in another way too. For the first time scientists on the ground, based at the Payload Operations Control Center, then located at the Johnson Space Center in Texas, were permitted to speak directly to the astronauts – before that point the assigned ‘Capcom’ had been the sole voice on-orbit crews would hear.

Jochen Graf, ESA Head of Spacelab Flight Operations: Before Spacelab that not even the Flight Director could talk directly to the astronauts. But it was needed, so the scientists could talk directly to the astronauts operating their equipment. Today astronauts can just phone down to Earth, but at the time this was quite new.

Opening up

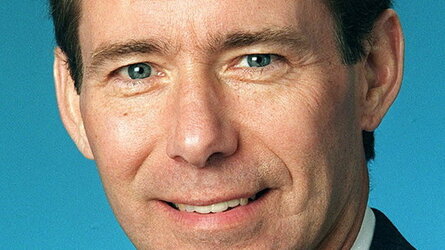

Brewster Shaw, NASA astronaut, STS-9/Spacelab-1 pilot: Probably the most difficult aspect of the whole thing was after we got on orbit, we couldn’t get the hatch open, so we couldn’t get back into the Spacelab at all. I mean I remember thinking ‘Holy smokes. This mission’s not going to go well if we can’t get into the lab.’ [Laughs]. But we finally managed to get the get open, but it took us a few minutes. Looking at Owen and Bob’s faces I remember thinking ‘Boy, these guys are seeing their lives pass in front of their face, if we can’t get in there to do the stuff that they’ve been training for all these years to do.’ But we did, and it was a very successful mission.

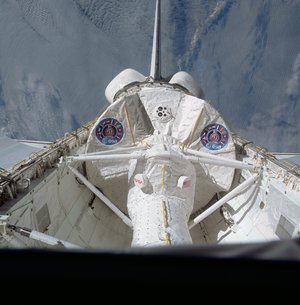

Ulf Merbold: Spacelab worked perfectly, it was quiet, had a good life support system, super air quality, nice illumination and other fantastic features, for example the airlock through which we could transfer experiments into space and back into the lab.

There was also a high-quality optical window in the ceiling of the module, so you could turn the Shuttle so that the window faced Earth for an undisturbed view. A camera system took distortion-free pictures, and in the few free moments between experiments we had breathtaking views through the viewports.

Brewster Shaw: Neither John [Young] or I felt too comfortable leaving the flight deck unattended, so we spent most of our time there. We had a few manoeuvres to do once in a while with the vehicle, and then the rest of the time you were monitoring systems. After a few days of that, boy, it got pretty boring, quite frankly. You spent a lot of time looking out the window and taking pictures and all that. But there was nobody to talk to, because the other guys were in the back end in the Spacelab working away, and, you know, you just had a ‘Gosh, I wish I had something to do’ kind of feeling. But the flight went fine and we did a great bunch of science.

Astronauts taking control

Ulf Merbold: As a crew we had different roles. For some experiments, we were merely lab technicians: we put materials sealed in cartridges into furnaces, heated and melted materials, pushed buttons and started computer programs. In other cases we were in scientific control of the experiments, and some of them were almost artistic, for example a silicon crystal experiment in a furnace called the Mirror Heating Facility. The investigator taught us to observe the liquid zone of the crystal rod, make an assessment of how long it would take until it would become unstable, what the material should look like and what to expect to be able to judge the next step.

These experiments had many functional objectives and, after a lot of training, the experimenters gave us carte blanche. ‘You have control because you know as much as we do, use your sense,’ they said. Of course this kind of relationship has two sides: we were proud that they trusted us, but we also felt a huge responsibility.

Knock, knock

The Spacelab shifts worked smoothly and efficiently – except for hearing occasional loud, nerve-wracking, bangs in the vicinity of the module.

Mel Brooks, NASA turned ESA member of Spacelab management team (from NASA Oral History interview): Every time I would go off shift, I'd go by the Flight Ops Management Room and see what they were doing, what problems they were chasing, and we even helped them once. They had some funny vibrations or sounds in the tunnel between the Orbiter and the Spacelab, and I heard them discussing it. In our material science doubles rack, we had a very sensitive vibration monitor, so we offered to give them some data from that thing if maybe they could help, when it happened, tell us what times they occurred and we'd give them the data.

These noises turned out to be caused by temperature-driven shifts of Spacelab’s transfer tunnel, like banging of terrestrial central heating pipes.

The first of many

Spacelab worked so well that the mission was assigned an extra day. The Shuttle returned after 10 days, seven hours and 47 minutes, completing 166 orbits of Earth. Spacelab-1 came back with around 250 gigabytes of data, including 20 million pictures. And this was only the first of 16 Spacelab flights, which continued operations until 1998 – a quarter of a century after Europe had begun the project.

Alan Thirkettle, ESA Spacelab engineer: All the Spacelab missions were really quite successful… we felt we’d come of age. We’d really gone through a learning phase that was exciting as hell, we’d enjoyed ourselves enormously, we’d all made very good friends and we were ready for the next challenge, that was for sure.

Walter Cugno, Spacelab product assurance engineer at Aeritalia (today VP of Exploration and Science, Thales Alenia Space): For Italy, Spacelab began an industrial lineage that evolved from thermomechanical capability to the design, development, manufacturing, integration and testing of today’s fully outfitted, pressurised modules – through Columbus and our other ISS modules, the ATV and Cygnus cargo vehicles, modules for the Gateway and private Axiom stations, all the way to research on habitable modules for the surface of the Moon.

Ulf Merbold went on to fly again on the Shuttle, and then on a Soyuz flight to the Mir space station.

Ulf Merbold: Spacelab in terms of its power as scientific platform was by far superior as compared to the Mir station. We had much more computing power, much wider bandwidth to transmit data to the ground…

Spacelab always worked without problem and I think that was actually the ticket for us to Europeans to join the club of those agencies who at the end started to work together building the ISS.

Access the video

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland