It takes a team

Look again at that Space Station. That’s there. That’s home for a crew of six astronauts. That’s us too. On it every human being lives out their lives, performs science and maintains the spacecraft with the support of a whole team on Earth.

This week ESA is highlighting the role of the European teams that make a space mission possible – from preparations to launch, from continuous research to testing new equipment.

Read on for our bi-weekly update on the joint efforts between ground staff and our ambassadors in space to keep the orbital laboratory running.

Space upgrades

Two spacewalks (also called Extra-Vehicular Activity, or EVA) took place just one week apart, on 22 and 29 March, shortly after the arrival of three new astronauts to arrive at the Space Station. The full crew of six worked together to upgrade the International Space Station’s power storage capacity.

ESA astronaut Thomas Pesquet was the European link to the first spacewalk to replace old nickel-hydrogen batteries with newer, more powerful lithium-ion batteries.

On Station, Thomas says preparation begins around two weeks ahead, with a set of procedures called the “Road to EVA”.

“Preparing for a spacewalk will take up two to three hours of your schedule every day. Many people have been involved in the preparation, and the risks are so much higher when you are outside the Space Station,” he explains.

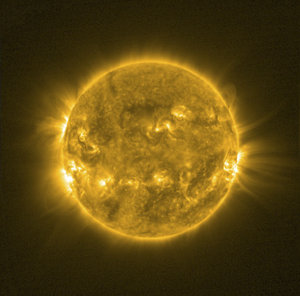

Another element outside the Space Station also got an upgrade. The Atmosphere–Space Interactions Monitor that monitors thunderstorms and lightning phenomena from a vantage point at Europe’s Columbus laboratory received better software.

It took two days for the European teams at the Belgian User Support and Operations Centre to reset the system and equip the space-based storm hunter with higher accuracy to continue its observations of sprites, blue jets and elves in the upper atmosphere.

The science teams welcomed software upgrade that came a week after the release of a paper about the payload by a prestigious research publication.

And some downgrades too

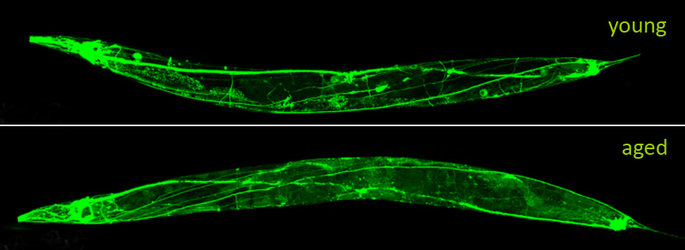

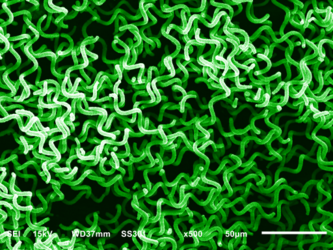

Space takes its toll on an astronaut’s body. In weightlessness, muscles lose functionality and mass, and astronauts exercise for about two hours a day to prevent muscle wasting away. The Myotones experiment focuses on resting muscle tone.

NASA astronaut Christina Koch used a non-invasive, smart-phone-sized device to measure the health of several muscles and tendons in her body, some of them known to be affected by atrophy and loss in strength during extended inactivity periods. Results could lead to the development of alternative rehabilitation treatments on Earth.

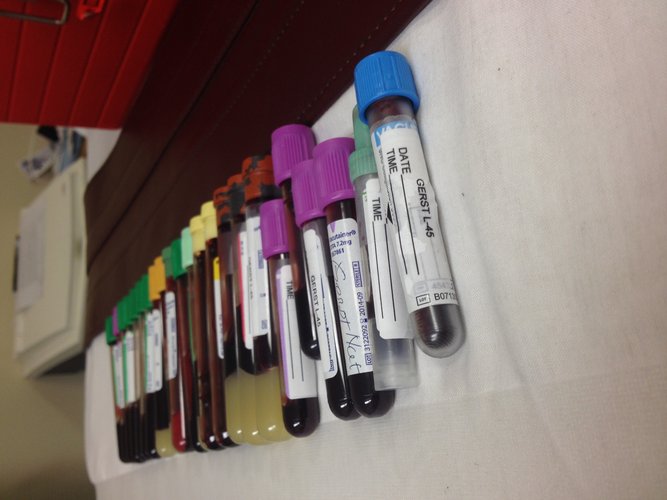

Bone loss and its recovery is another major concern not only for astronauts, but also for people affected by ageing and immobilisation. Studying what happens during long periods in space offers a good insight into osteoporosis. Russian cosmonaut Alexei Ovchinin drew a blood sample for the EDOS-2 experiment to monitor how his body copes with bone renewal in orbit.

The way astronauts sense the passing of time seems to be altered in space. Nick Hague carried out his first session of the Time Perception experiment wearing a virtual reality headset and headphones hooked up to a computer. During this experiment, astronauts are asked to estimate the amount of time elapsed between two events, react to stimuli and judge the length of a minute.

Automated science

There are experiments on the Space Station running on their own, too. Besides punctual human interventions and remote teleoperations, the following research continued producing science onboard: Compacted Granulars, ICE Cubes and Matiss.