The toxic side of the Moon

When the Apollo astronauts returned from the Moon, the dust that clung to their spacesuits made their throats sore and their eyes water. Lunar dust is made of sharp, abrasive and nasty particles, but how toxic is it for humans?

The “lunar hay fever”, as NASA astronaut Harrison Schmitt described it during the Apollo 17 mission created symptoms in all 12 people who have stepped on the Moon. From sneezing to nasal congestion, in some cases it took days for the reactions to fade. Inside the spacecraft, the dust smelt like burnt gunpowder.

The Moon missions left an unanswered question of lunar exploration – one that could affect humanity’s next steps in the Solar System: can lunar dust jeopardise human health?

An ambitious ESA research programme with experts from around the planet is now addressing the issues related to lunar dust.

“We don’t know how bad this dust is. It all comes down to an effort to estimate the degree of risk involved,” says Kim Prisk, a pulmonary physiologist from the University of California with over 20 years of experience in human spaceflight – one of the 12 scientists taking part in ESA’s research.

Nasty dust

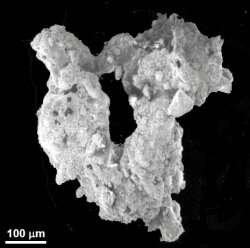

Lunar dust has silicate in it, a material commonly found on planetary bodies with volcanic activity. Miners on Earth suffer from inflamed and scarred lungs from inhaling silicate. On the Moon, the dust is so abrasive that it ate away layers of spacesuit boots and destroyed the vacuum seals of Apollo sample containers.

Fine like powder, but sharp like glass. The low gravity of the Moon, one sixth of what we have on Earth, allows tiny particles to stay suspended for longer and penetrate more deeply into the lung.

“Particles 50 times smaller than a human hair can hang around for months inside your lungs. The longer the particle stays, the greater the chance for toxic effects,” explains Kim.

The potential damage from inhaling this dust is unknown but research shows that lunar soil simulants can destroy lung and brain cells after long-term exposure.

Down to the particle

On Earth, fine particles tend to smoothen over years of erosion by wind and water, lunar dust however, is not round, but sharp and spiky.

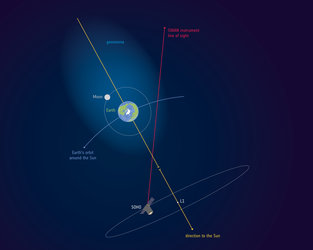

In addition the Moon has no atmosphere and is constantly bombarded by radiation from the Sun that causes the soil to become electrostatically charged.

This charge can be so strong that the dust levitates above the lunar surface, making it even more likely to get inside equipment and people’s lungs.

Dusty workplace

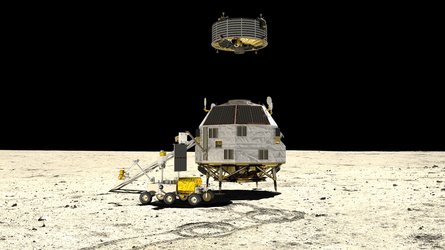

To test equipment and the behaviour of lunar dust, ESA will be working with simulated Moon dust mined from a volcanic region in Germany.

Working with the simulant is no easy feat. “The rarity of the lunar glass-like material makes it a special kind of dust. We need to grind the source material but that means removing the sharp edges,” says Erin Tranfield, biologist and expert in dust toxicity.

The lunar soil does have a bright side. “You can heat it to produce bricks that can offer shelter for astronauts. Oxygen can be extracted from the soil to sustain human missions on the Moon,” explains science advisor Aidan Cowley.

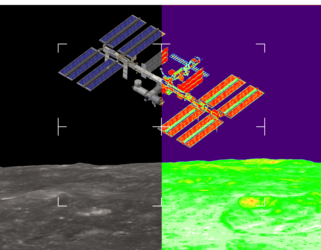

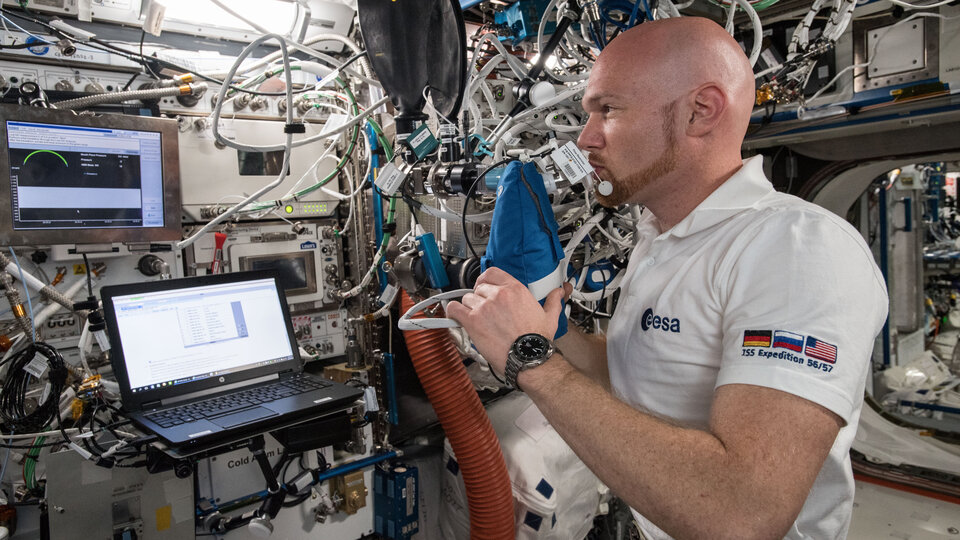

This week ESA is hosting a workshop on lunar resources at the European Space Research Technology Centre in the Netherlands, meanwhile in space ESA astronaut Alexander Gerst is running a session of the Airway Monitoring experiment to monitor lung health in reduced gravity – preparing for a sustainable return to our nearest neighbour in the Solar System.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland