See-through metals

Astronauts on the International Space Station have begun running an experiment that could shine new light on how metal alloys are formed.

How humanity has mastered metallurgy is synonymous with progress, with historians labelling periods such as the Bronze Age and the Iron Age.

Most metals used today are mixtures – alloys – of different metals, combining properties to make lighter and stronger materials.

Like baking a cake, the result depends on more than just adding the right ingredients: casting is influenced by furnace temperatures and the cooling process. Some metals are even cast in hypergravity centrifuges in the quest for the perfect alloy.

Alloys are everywhere now, from the smartphone in your pocket to aircraft. Making lighter, resistant, self-healing or even supple alloys obviously benefits industry and consumers alike.

Solving the problem of transparency

It is no wonder that we would love to peer into the inner workings of metal casting to see what is happening with our own eyes. Ideally, we should observe the process without gravity adding its extra layer of complexity. The problem, of course, is that metals are not transparent.

ESA is running X-ray experiments on suborbital rockets but these are limited to 13 minutes of weightlessness at a time and X-rays do not reveal all.

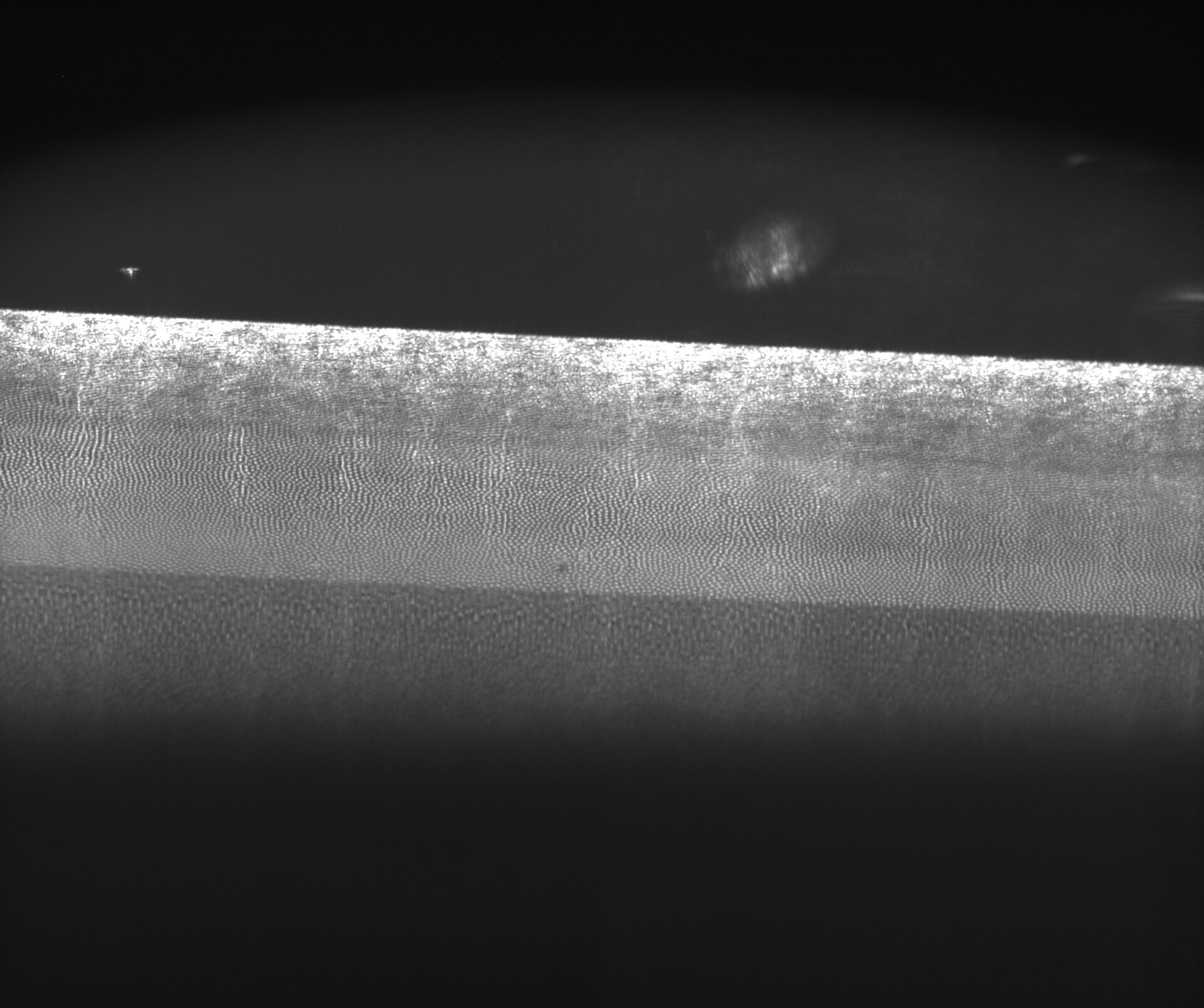

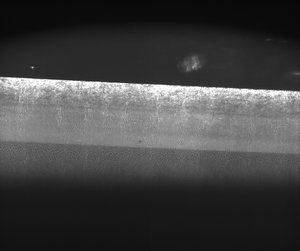

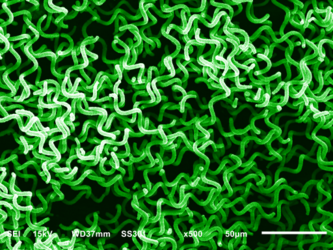

Instead, researchers looked at a stand-in for metals and found organic materials, carefully chosen to be transparent while solidifying like a metal.

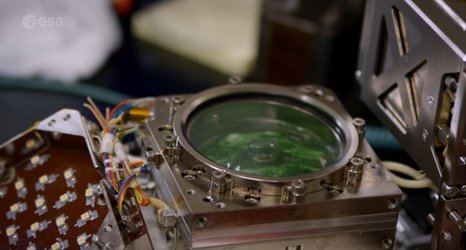

A first batch of mixtures arrived at the Space Station on 18 December: succinonitrile, D-camphor and neopentyl glycol were delivered by a Dragon spacecraft inside a glass-wall cartridge together with a miniature toaster. This Bridgman furnace is similar to a conveyor-belt oven found in factories or fast-food restaurants. The cartridges pass through the heating element at an agonisingly slow pace: they take upwards of two days to travel 1 mm, but the experiment will run on its own for several weeks.

Melting plastic

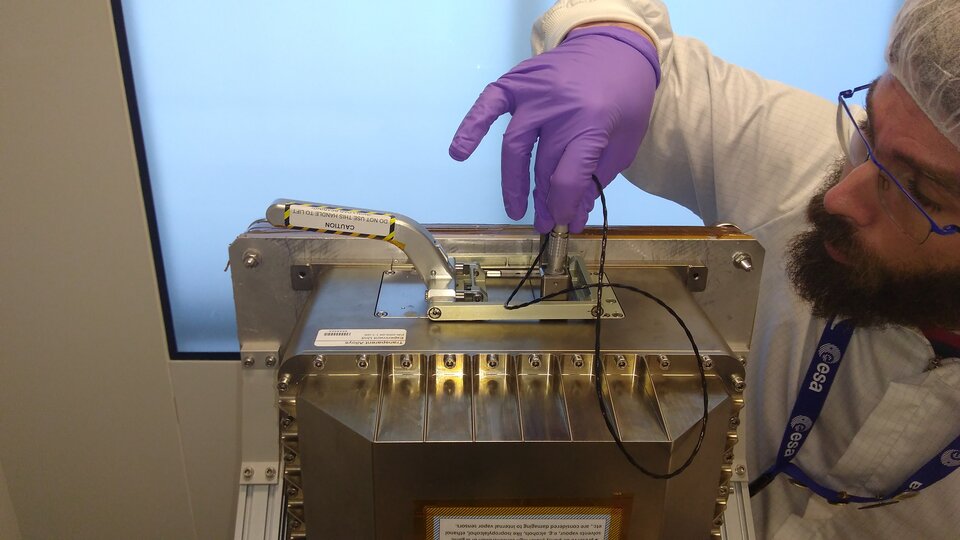

An astronaut set up the Transparent Alloy furnace inside ESA’s self-contained glovebox for safety and inserted the first cartridge.

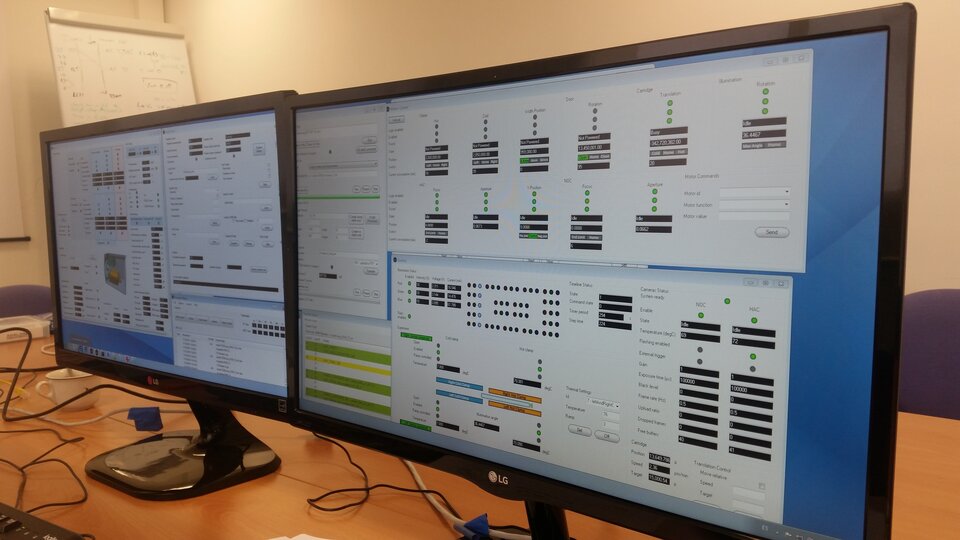

A hard disk is recording the microscopic view from two video cameras, while operators at the Spanish control centre in Madrid can highlight different features using an array of coloured lights.

These experiments into fundamental phenomena are allowing scientists to understand and then control processes. Who knows what amazing metals might be created? The next metal age might just be something we can’t imagine right now.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland