Life of a foam

A fine coffee froth does not last forever. The bubbles that make the milk light and creamy are eventually torn apart by the pull of gravity. But there is a place where foams have a more stable life – in the weightless environment of the International Space Station, bubbles don’t burst so quickly and foams remain wet for longer.

Beyond the pleasures of sipping a cappuccino with its signature froth, the presence of foams in our daily lives extends to food, detergents, cosmetics and medicines. However, creating the perfect bubble for the right foam is tricky.

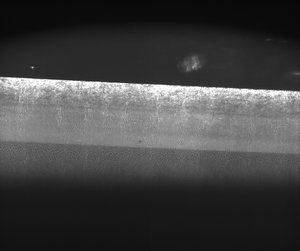

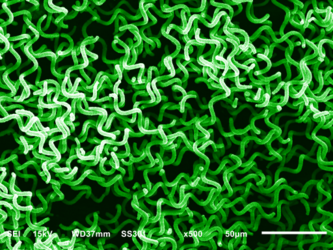

On Earth, the mixture of gas and liquid that makes up a foam quickly starts to change. Gravity pulls the liquid between the bubbles downwards, and the small bubbles shrink while the larger ones tend to grow at the expense of others. Due to the drainage, coarsening and rupture of the bubbles, foam starts to collapse back to a liquid state.

A foam’s existence in space is marked by more equilibrium because drainage is suppressed. Bubble sizes are evenly spread and that makes it easier for scientists to study it in more detail.

Lessons on foams in space

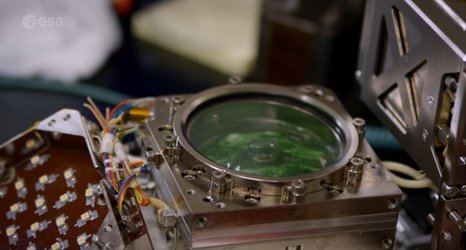

In 2009, ESA astronaut Frank De Winne ran the Foam Stability experiment on the International Space Station. Frank shook several liquid solutions contained in 60 closed cells and recorded what happened next. The samples ranged from pure water to protein-based fluids, like the ones used for chocolate foams, and antifoaming agents.

After just ten seconds, fluids stabilised more quickly and produced more foam than on Earth. Scientists discovered that it was possible to create super stable foams in zero gravity.

Antifoaming agents had a reduced effect in microgravity, a new behaviour that took researchers by surprise. On a parabolic flight, 20 seconds of microgravity were enough to make foams out of pure water.

Access the video

From space to your bubble

Foam research in microgravity allowed researchers to better understand foam behaviour and improve food production.

“The stability of foam bubbles can enhance the quality, texture, taste and shelf-life of some foods and drinks. It was a game changer for our business,” points out Cécile Gehin-Delval, senior R&D specialist from Nestlé research laboratories in Switzerland.

“This study helped us to create near-to-perfect air bubbles for our dairy, ice cream and pet food products,” she adds.

Foams can also be metallic, and have incredible structural characteristics. Aluminium foam, for example, is as strong as pure metal but much lighter. This research can help in the construction of light-weight and sturdy aerospace structures and new shielding systems for diagnostic radiology equipment in hospitals.

“All this knowledge harvested in orbit will have, sooner or later, an impact on our daily lives. I believe fundamental research in space can make the world a better place,” reflects bioengineer Leonardo Surdo.

“Think outside your bubble next time you look at a foam, be it in your beer, cake frost or shaving gel,” he adds.