Herschel discovers water vapour around dwarf planet Ceres

ESA’s Herschel space observatory has discovered water vapour around Ceres, the first unambiguous detection of water vapour around an object in the asteroid belt.

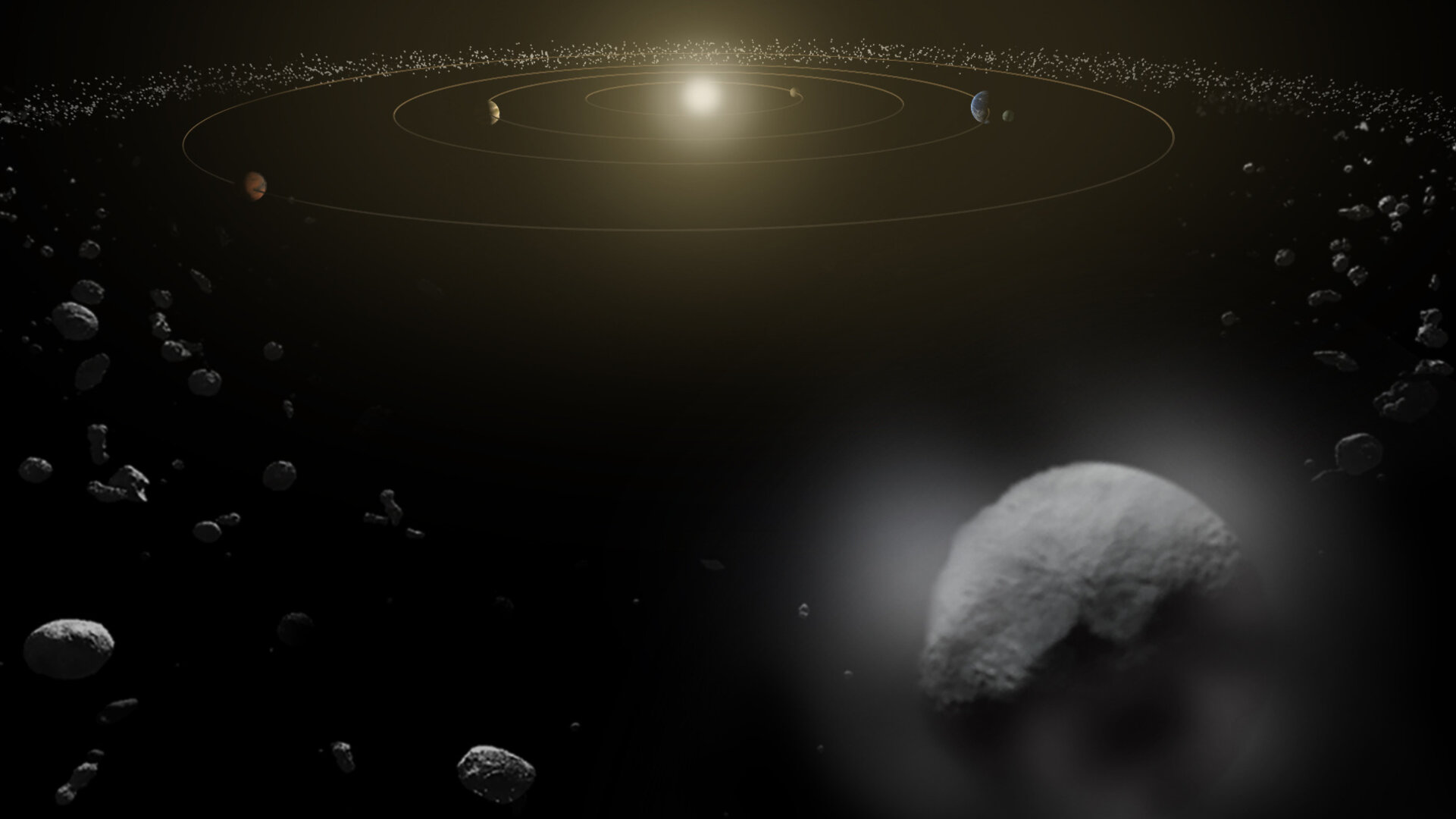

With a diameter of 950 km, Ceres is the largest object in the asteroid belt, which lies between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. But unlike most asteroids, Ceres is almost spherical and belongs to the category of ‘dwarf planets’, which also includes Pluto.

It is thought that Ceres is layered, perhaps with a rocky core and an icy outer mantle. This is important, because the water-ice content of the asteroid belt has significant implications for our understanding of the evolution of the Solar System.

When the Solar System formed 4.6 billion years ago, it was too hot in its central regions for water to have condensed at the locations of the innermost planets, Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars. Instead, it is thought that water was delivered to these planets later during a prolonged period of intense asteroid and comet impacts around 3.9 billion years ago.

While comets are well known to contain water ice, what about asteroids? Water in the asteroid belt has been hinted at through the observation of comet-like activity around some asteroids – the so-called Main Belt Comet family – but no definitive detection of water vapour has ever been made.

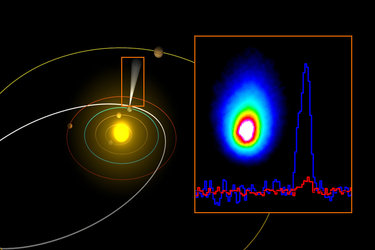

Now, using the HIFI instrument on Herschel to study Ceres, scientists have collected data that point to water vapour being emitted from the icy world’s surface.

“This is the first time that water has been detected in the asteroid belt, and provides proof that Ceres has an icy surface and an atmosphere,” says Michael Küppers of ESA’s European Space Astronomy Centre in Spain, lead author of the paper published in Nature.

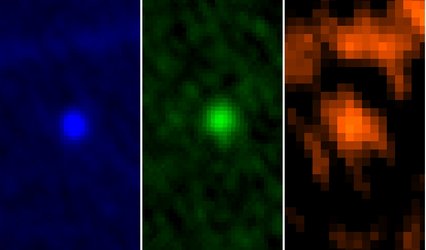

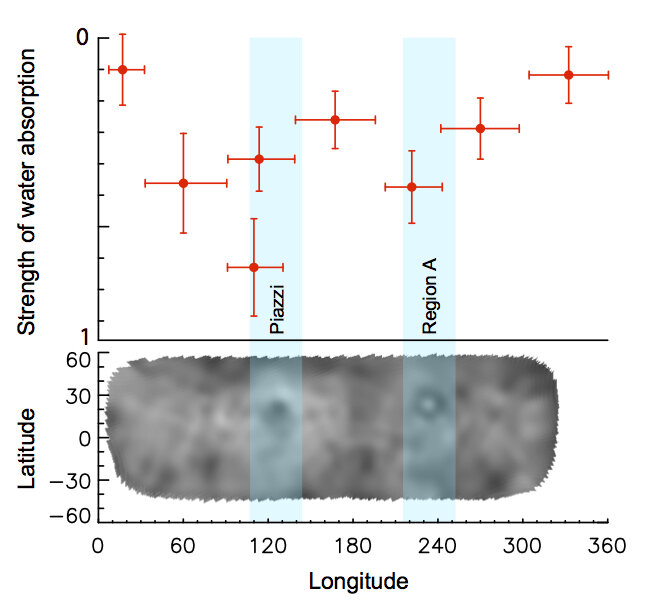

Although Herschel was not able to make a resolved image of Ceres, the astronomers were able to derive the distribution of water sources on the surface by observing variations in the water signal during the dwarf planet’s 9-hour rotation period. Almost all of the water vapour was seen to be coming from just two spots on the surface.

“We estimate that approximately 6 kg of water vapour is being produced per second, requiring only a tiny fraction of Ceres to be covered by water ice, which links nicely to the two localised surface features we have observed,” says Laurence O’Rourke, Principal Investigator for the Herschel asteroid and comet observation programme called MACH-11, and second author on the Nature paper.

The most straightforward explanation of the water vapour production is through sublimation, whereby ice is warmed and transforms directly into gas, dragging the surface dust with it, and thus exposing fresh ice underneath to sustain the process. Comets work in this fashion.

The two emitting regions are about 5% darker than the average on Ceres. Able to absorb more sunlight, they are then likely the warmest regions, resulting in a more efficient sublimation of small reservoirs of water ice.

An alternative possibility is that geysers or icy volcanoes – cryovolcanism – play a role in the dwarf planet’s activity.

Much more detailed information on Ceres is expected soon, as NASA’s Dawn mission is currently en route there for an arrival in early 2015. It will provide close-up mapping of the surface and monitor how the water activity is generated and varies with time.

“Herschel’s discovery of water vapour outgassing from Ceres gives us new information on how water is distributed in the Solar System. Since Ceres constitutes about one fifth of the total mass of asteroid belt, this finding is important not only for the study of small Solar System bodies in general, but also for learning more about the origin of water on Earth,” says Göran Pilbratt, ESA’s Herschel Project Scientist.

More information

“Localised sources of water vapour on dwarf planet (1) Ceres,” by M. Küppers et al. is published in Nature 23 January 2014.

Ceres was observed on four occasions between November 2011 and March 2013 initially as part of the MACH-11 (Measurements of 11 Asteroids and Comets with Herschel) Guaranteed Time Programme, and complemented by two additional Director’s Discretionary Time observations that confirmed the tentative detection and measured the variation in water vapour as a function of rotation period.

For further information, please contact:

Markus Bauer

ESA Science and Robotic Exploration Communication Officer

Tel: +31 71 565 6799

Mob: +31 61 594 3 954

Email: markus.bauer@esa.int

Michael Küppers

European Space Agency, ESAC

Email: michael.kueppers@sciops.esa.int

Laurence O’Rourke

Programme PI for MACH-11

European Space Agency, ESAC

Email: Laurence.O’Rourke@esa.int

Göran Pilbratt

ESA Herschel Project Scientist

Tel: +31 71 565 3621

Email: gpilbratt@rssd.esa.int

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland