Accidental space scientist: An interview with Gerhard Schwehm

He always wanted to be an atmospheric physicist. But, fortunately for us, a game of volleyball changed his life. Today, Gerhard Schwehm is now a major figure in space science. As well as being Head of Planetary Science at ESA, he is also the Project Scientist on ESA’s forthcoming ambitious Rosetta mission to orbit and land on a comet.

Gerhard Schwehm

Head of Planetary Science, ESA, and Project Scientist, Rosetta mission.

Born: 13 March 1949 in Ludwigshafen am Rhein, Germany.

PhD in Applied Physics, Ruhr-University, Bochum; after working at ESOC on the modelling of the dust environment for Halley’s Comet, he was hired as ESA’s first planetary scientist, working on the Giotto mission, which gave us the very first close-up images of a comet nucleus.

He became lead scientist on the Rosetta mission in 1985.

Married with two small children, Gerhard enjoys modern literature and art, classical music, good food and wine, though naturally his family is his first priority in his very sparse spare time.

Cometary matter gives us a perfect glimpse back to our very beginnings.

ESA: When did you first become interested in space science?

Gerhard Schwehm

Of course, I had a natural interest in the achievements of the early spaceprobes and especially manned spaceflight, starting with Yuri Gagarin and the first Moon landing, which I followed with my fellow students in my first year at university, but I really wanted to study the dynamics of Earth’s atmosphere in detail, which was an emerging field at that time with satellite data becoming available.

After my move to Bochum, I joined a volleyball team and one of my team mates turned out to be a young professor of atmospheric physics. He asked me to work with him, however, it turned out that his boss needed somebody urgently to fill a role on a space science research project. As he was the boss, he got the final say and so I went to work for him. I have been in this field ever since!

Comets make wonderful laboratories for chemical reactions.

ESA: You have been working on the Rosetta mission for some years – why do you think it is so important?

Gerhard Schwehm

Comets provide the means for us to access the most primitive matter in the Solar System. The specific evolutionary history of comets has preserved their matter exactly as they were before the ‘Solar Nebula’, the huge cloud of gas and dust out of which the Solar System was born. Apart from some alterations by radiation, this matter gives us a perfect glimpse back to our very beginnings.

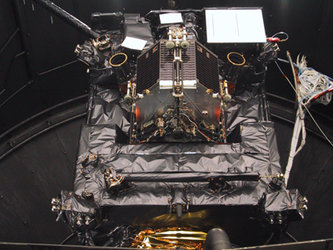

With Rosetta, we will learn in detail how comets work. I believe all of us have been impressed by watching Comet Hale-Bopp in the night sky a couple of years ago. We got a lot of observations with ground-based telescopes but we still don’t know the full physics of comets, their structure for example, and how they were formed in the first place. Once we learn more about this process, we have reached another big step in understanding how planets are formed too.

ESA’s Giotto mission showed us that comets are made of up to 80 per cent water and contain a huge variety of complex molecules. Together with the dust, the large surface area and the amounts of radiation to which they are exposed in space, such as ultraviolet radiation, they make wonderful laboratories for chemical reactions. It will be one of the most exciting prospects of the mission to find out exactly what chemistry is going on.

Finally, we have a great chance to find out how comets affected the evolution of the Earth. For example, we believe that the Earth underwent a period of heavy bombardment by comets and suchlike, but we still don’t know exactly what role comets played in the formation of our atmosphere, or whether they contributed to the amount of water found on Earth.

Some of the instruments on Rosetta and its lander will study the composition of the molecules - each with its own chemical ‘fingerprint’ that cannot be destroyed. We can examine these ‘fingerprints’ and find the answers to these most fascinating questions.

The most serious challenge is that the mission takes so long to reach its target.

ESA: What are the greatest challenges facing Rosetta?

Gerhard Schwehm

The launch of the spacecraft will be a very big moment. Once it has left the launch pad, we have to wait one and a half hours for the ignition of the upper stage which will put it on its interplanetary trajectory - that will be a nerve-racking very long wait not only for me!

But maybe the most serious challenge is that the mission takes so long to reach its target. It will take ten years to get to Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, during which time we have to ensure that we keep a core team together, so that the know-how is preserved until the moment it is needed.

ESA: How will the Rosetta team cope with that?

Gerhard Schwehm

We have plans to bring the science teams and operations team together regularly every six months during the journey to keep the team spirit up and prepare the comet phase. Also the Earth fly-bys, the Mars fly-by and the close fly-by of an asteroid will be opportunities to exercise the whole system and do ‘early’ science.

There is plenty of preparation work to be done before Rosetta goes into orbit around the nucleus of the comet and we will use every opportunity to get acquainted with all procedures to ensure that we are ready for the exciting times when we reach the comet.

ESA: What about at the end of this journey?

Gerhard Schwehm

Towards the end of its journey, Rosetta will have about two years of hibernation before it is woken up again as it reaches its target. We have to do this because Rosetta will be travelling so far away from the Sun that even with its newly developed ‘low-intensity, low-temperature’ solar cells, its solar panels will not provide enough energy to power the spacecraft. During the hibernation period, there will be no communication at all with Rosetta, so it will be a very anxious time.

Fortunately, I have had some experience of this when I was working on the Giotto mission. Giotto was in hibernation between 1986 and 1990, when it was decided to wake it up so that it could be aimed at Comet Grigg-Skjellerup.

Giotto was never designed to be re-activated, so we were uncertain when we sent it the first commands. However, we received a signal from Giotto within milliseconds of the predicted time, which was a wonderful feeling. It went on to make the closest ever fly-by of a comet to date.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland