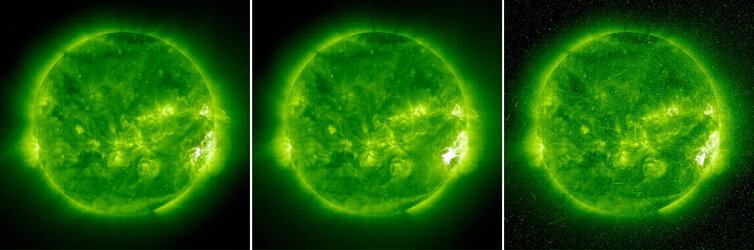

The Sun comes back to life

After the most profound lull in solar activity for nearly a century, the Sun is finally coming back to life. But will the solar activity return to previous levels? ESA’s venerable solar watchdog SOHO is there, watching and measuring, providing unique information about our nearest star.

It was the perfect Christmas present for solar physicists. In mid-December 2009, the largest group of sunspots to emerge for several years manifested itself on the solar surface. It occurred just as some solar physicists were beginning to wonder if large sunspots would ever return. “This last minimum was much deeper and longer than anybody predicted,” says Bernhard Fleck, ESA’s SOHO Project Scientist, “We were beginning to joke that we had entered another Maunder minimum.”

The Maunder minimum occurred between 1645 and 1715, when sunspots, the visible markers of solar activity, were largely absent from the Sun. The last two years have been the same, with the Sun presenting a spotless face for more than 70% of the time.

Astronomers are used to seeing the Sun sweep through a cycle of activity that lasts approximately 11 years. But until December last year, the Sun had seemed reluctant to start up again. In mid-January, an even larger sunspot group emerged and, most recently, several big, active areas have been crossing the face of the Sun. Yet it is premature to believe that the Sun is ramping up for another energetic cycle of activity.

The strength of the upcoming solar cycle is determined by the strength of magnetism at the poles of the Sun, and this is currently very weak. The polar field provides the magnetic ‘seeds’ for the next cycle’s sunspots by being swallowed down inside the Sun, somehow rejuvenated and then returned to the surface to appear as the dark blemishes.

So, although the Sun is coming back to life, we should not expect that much activity according to Fleck. “I think we are heading for something like the early 20th century when everything was much less active,” he says. Historical records show that, until the last few years, the solar cycle has been unusually active. So, rather than a sudden drop in activity, this is more like a return to normality.

“When SOHO was launched almost 15 years ago, understanding the solar cycle was not one of its scientific objectives, now it is one of the key questions,” says Fleck.

As newer spacecraft, such as NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory are launched, SOHO’s continued observations will provide essential calibration data for the newer instruments, ensuring that the astronomers can compare the datasets accurately. And SOHO still has one unique capability: it remains the only spacecraft in line with the Sun that can watch for ‘coronal mass ejections’ coming straight for Earth, which can disrupt telecommunications, GPS and power lines.

For more information:

Bernhard Fleck, ESA SOHO Project Scientist

Email: Bfleck @ esa.nascom.nasa.gov

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland