CryoSat-2 Spacecraft Operations Manager: Interview with Nic Mardle

Nic Mardle is the Spacecraft Operations Manager (SOM) for

Nic Mardle is from England, and holds a degree in Aerospace System Engineering from the UK’s Southampton University. She began her career at British Aerospace, where she worked in the Assembly, Integration and Verification section performing a number of launch campaigns for the company’s telecom satellites. During 1991–93, she was part of the industrial team providing support to the Olympus recovery team, first at ESOC and then at Fucino, Italy.

From 1993-98, she worked first on ESA's ERS-1 and -2 missions as a contract engineer and then in Australia as senior vice president for operations at Worldspace, a broadcast satellite operator. In 2003, she joined the Agency as a regular staff member as SOM for the original CryoSat. In her spare time, she practises Katori Shintō-ryū, a Japanese martial art.

ESA: What is the main challenge in developing the CryoSat-2 flight control systems and fostering a new flight team?

Nic Mardle

The new CryoSat isn't merely a rebuilt version of the first one - the new satellite and the ground segment embody an almost totally updated set of systems and procedures. We have had to re-validate virtually all the flight control systems - and we've got an almost entirely new flight control team. One additional challenge is that all of the CryoSat-2 teams; ESOC, ESTEC and Astrium, are smaller than the original, we have all had to become involved in more activities and in areas outside of our previous expertise. My main goal now is to ensure the best performance from the team here so that they are able to meet the challenges and are fully ready to support the mission.

It helps if you are a little bit of a pessimist – never take anything on faith and make sure you verify everything.

ESA: In 2005, CryoSat was lost shortly after lift off due to launcher failure. How did that affect you and the team?

Nic Mardle

We were incredibly disappointed about the loss of the first CryoSat. It was, however, extremely gratifying when the Agency and the science community supported the construction of a replacement satellite, indicating that the mission was still vitally important. The team worked hard to close the issues of CryoSat and start immediately to support the definition and procurement of CryoSat-2. So, in spite of the disappointment of the failure, we were kept busy and motivated. Some of the team were kept busy in other ways as they were reassigned to other Earth observation missions, including GOCE and ADM-Aeolus.

For those of us on the first CryoSat now involved in the Launch and Early Orbit Phase of CryoSat-2 – and for the CryoSat-2 launch we were able to re-recruit several of the original launch team to join us – there is an additional sense of trepidation but also an additional level of excitement, as we are finally launching the satellite that we unfortunately lost over four years ago.

There is an additional level of excitement, as we are finally launching the satellite that we unfortunately lost over four years ago.

ESA: What do you enjoy about your job? What gets you bouncing out of bed in the morning?

Nic Mardle

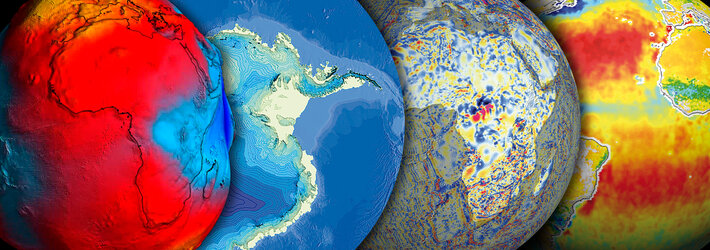

Normally, as an operations engineer, properly controlling the satellite is paramount and the scientific or commercial returns are less obvious. But CryoSat-2 is the first satellite I've worked on where I also feel a strong commitment to the science goals of the mission. The results that will come from CryoSat are crucially important for our understanding of climate change and I am really motivated to help make the mission a success.

ESA: How did you get involved with spacecraft operations?

Nic Mardle

I have always been interested in space, but didn't plan specifically for a career in this area. In 1991, my boss at British Aerospace, now Astrium, lent me out to provide Industry support to the Agency in the recovery of Olympus, which had suffered a major malfunction and was completely frozen with no power or any control.

The mission had to be recovered from a basically dead situation; initially decoding the partial telemetry frames by hand, then commanding heaters individually to ensure that the central processor had enough power to remain powered as it rotated helplessly in and out of sunlight, then thawing the batteries and the reaction control subsystem, finally receiving the first full format of telemetry when the attitude and orbit control system could be commanded into a Sun acquisition mode - and all this in the 72 days it took Olympus to circle the world and return to its nominal orbital slot.

It was such a fantastic experience working in the operational environment with the Industrial and ESA teams that when later opportunities came up to work with ESA and then to join permanently, I happily took them.

ESA: What do you advise anyone who is interested in working in a space field?

Nic Mardle

People get into a space career from an incredibly wide range of backgrounds; there is no one set of characteristics that define who you should be. Follow your interests, and if they lead to a job related to space, then make sure that you don't get overly focused on any one speciality. To be a good satellite operations engineer, for example, requires that you thoroughly understand every portion of the ground segment and the systems that control a mission and how they all fit together. You’ve got to think beyond any one box.

It also helps if you are a little bit of a pessimist – never take anything on faith and make sure you verify everything. Plan for the worst and that way you’ll be ready to handle any problems that a mission may throw at you.

ESA: What do you do after work to relax?

Nic Mardle

For some years now, I've been practising Katori Shintō-ryū, one of the oldest Japanese martial arts. I try to practise weekly at a club near Darmstadt, but also attend seminars held at different clubs around Europe throughout the year. Lately, with the build-up to launch, I haven't had as much time to participate. But if all goes well, I will take my next grading later this summer. It’s an excellent way to unwind from the daily challenges of getting CryoSat ready to go.

Editor's note:

This is one in a series of interviews with a few of the key people that are involved in the CryoSat mission. Please check back as the list will be added to over the coming weeks.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland