Growing tissues in space

Tissue engineering is a fast-developing field reaching new heights thanks to space research. An experiment on the International Space Station is opening up possibilities to grow artificial blood vessels for surgery on humans.

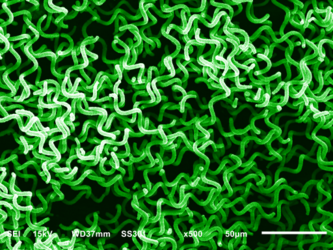

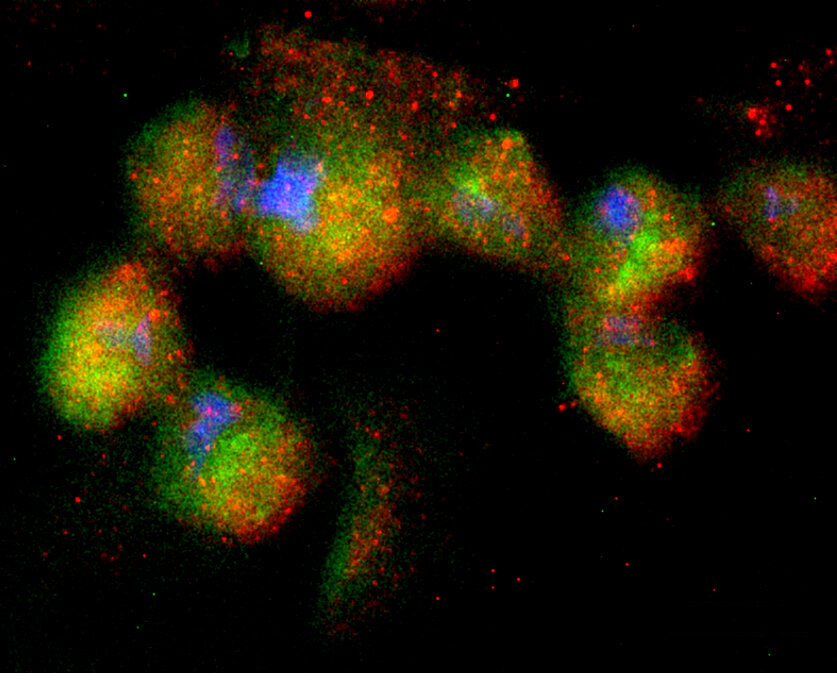

Most of the techniques to grow three-dimensional structures from human cells on Earth involve biocompatible scaffolds. In the lab, scientists use them to define the shape of the tissue and help cells stick to each other. A European experiment showed how cell cultures in microgravity do not need external support and could form rudimentary blood vessels naturally.

The Spheroids experiment looked at how the cells that form the inner layer of our blood vessels – the endothelial cells – react to microgravity on the space station.Endothelial cells control the contraction and expansion of our blood vessels, regulating blood flow to our organs and blood pressure.

Access the video

Weightlessness and lack of convection in orbit make an ideal combination to study these three-dimensional, complex structures.

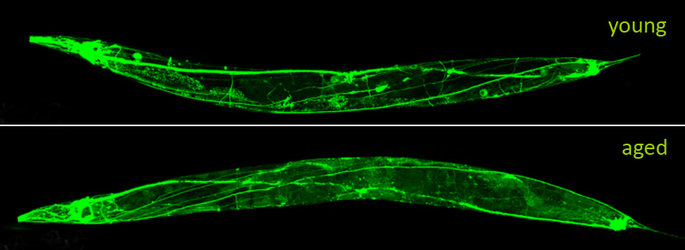

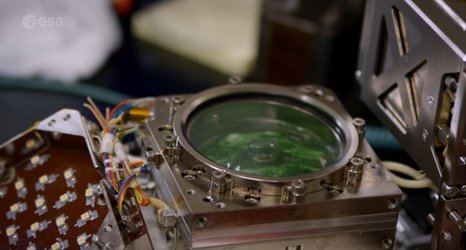

The human cells cultivated in space assembled into tubular structures, similar to the inner lining of blood vessels inside our bodies. The experiment had cells growing for 12 days inside ESA’s Kubik incubator to keep them at the right temperature.

“These tube-like aggregations resembled rudimentary blood vessels, something never achieved before by scientists cultivating cells on Earth,” says Daniela Grimm of the Otto von Guericke University Magdeburg, Germany. The Spheroids experiment ran on the International Space Station in 2016.

“Nobody knew how the cells would react to space. The Spheroids project has been an exciting adventure from the very beginning,” she adds.

Built in space for patients on Earth

With the samples back on Earth, scientists were pleasantly surprised to see how the cells formed three-dimensional spheroids aggregates by themselves.

“We learned new things about the tube formation mechanism, and the results confirmed that gravity has an impact on the way key proteins and genes interact,” explains Markus Wehland, a molecular biologist from the same university.

Laboratory and paperwork continues – how and why the cells accumulate into spheroids is still under investigation.

“We are culturing different cells to improve tissue engineering of artificial blood vessels,” Markus says. Combining the endothelial cells with other cultures, the team has even been able to ‘rebuild’ several layers of a blood vessel in a random positioning machine, a device that simulates microgravity on Earth.

Growing blood vessels in space could help engineer human tissues for transplants or for producing new drugs. Better techniques could eventually help replace damaged blood vessels for patients in need of transplants.

Astronauts will also benefit from the new knowledge about endothelial cells, since they show alterations in blood pressure during spaceflight.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland