Stressed in space

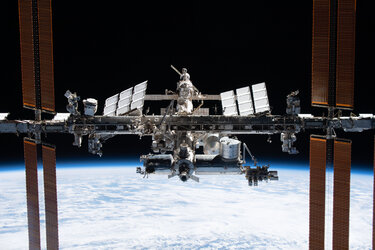

Living in space is a wonderful experience but it can take its toll on an astronaut’s body – half of astronauts return with weaker immune systems from the International Space Station. ESA astronaut and medical doctor André Kuipers remembers his six-month mission: “Back on Earth, I felt a hundred years old for a few months.”

Many ESA experiments are looking into why this happens and the most recent – Immuno – reveals some striking changes in astronaut immune systems.

Fight or flight

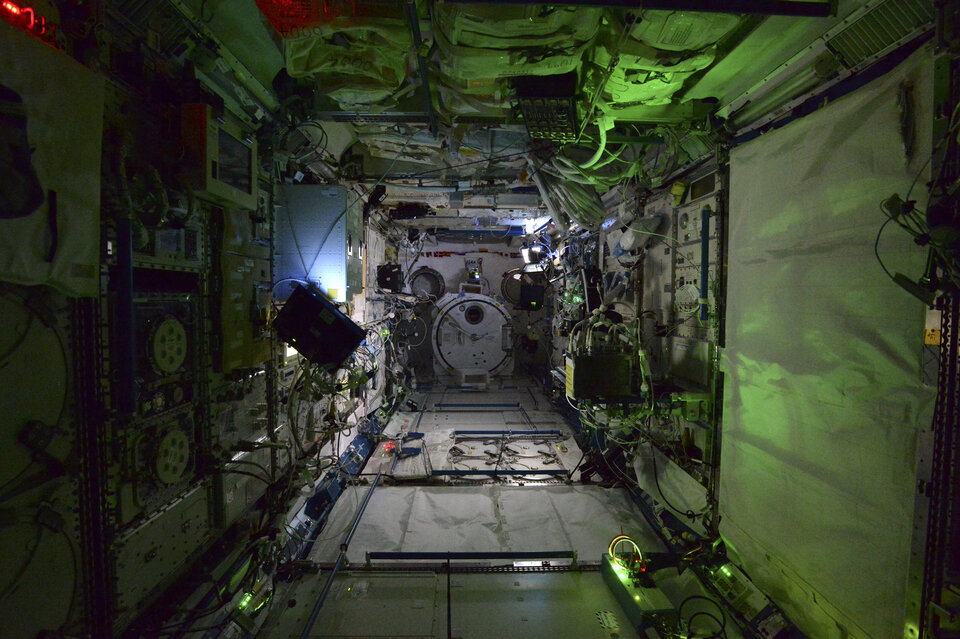

Stress is a response of the body as it adapts to hostile environments. This broad definition includes stress from speaking in front of an audience, stress from a wound or stress from living in weightlessness in a fragile spacecraft far from home.

The “feelings” are produced by the central nervous system working closely with our immune system. Stress in the central nervous system invariably influences the immune system and vice versa – people with stressful jobs seem more likely to get sick.

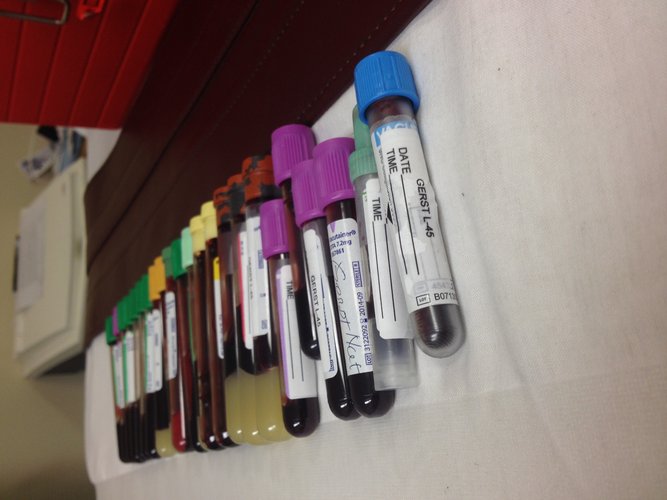

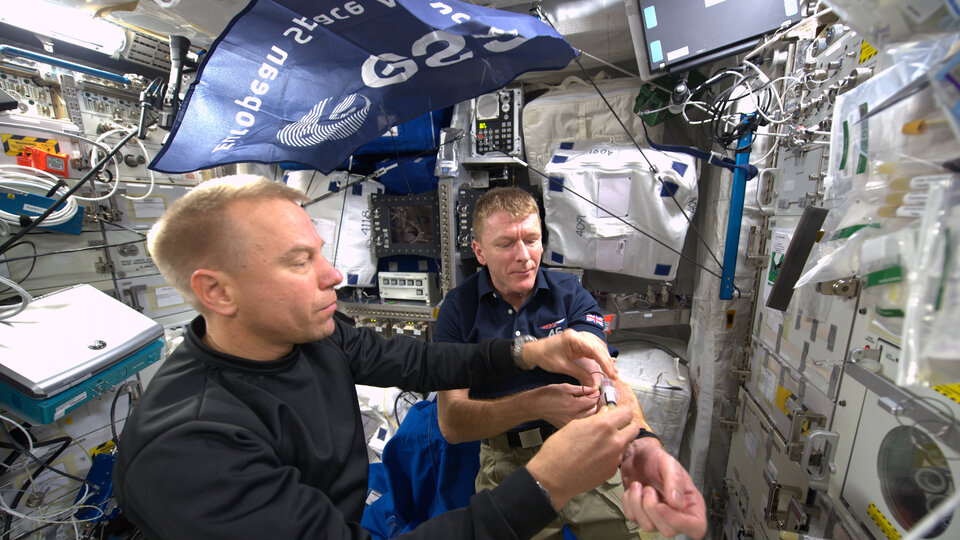

The Immuno experiment had a triple-pronged approach: a questionnaire asked astronauts to assess their own levels of stress while stress-related hormones were measured through saliva and urine samples, and blood samples were taken to analyse immune cell reaction to such environmental stress.

From astronauts to newborns

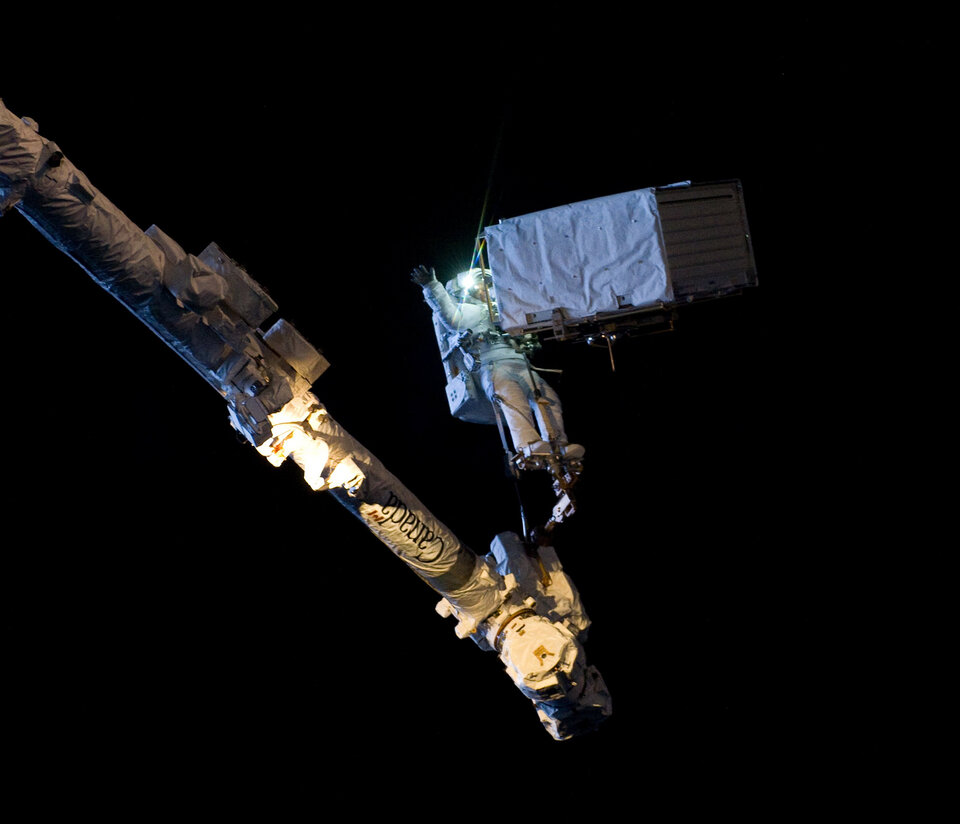

The research has taken five years to complete and involved meticulous planning to use the limited amount of blood that could be taken from the astronauts, stored in the Space Station’s –80°C freezers and returned to Earth.

Through necessity, the researchers developed new ways of analysing small quantities of blood, now being shared with the medical community. “Our methods would interest doctors that care for newborns, who have little blood to give for analysis,” notes Prof. Alexander Choukèr, the lead investigator. His team recently completed a clinical study in adults suffering from inflammation using these tests.

Rambo-style vs paralysed immune response

Immuno’s 12 cosmonauts were pretty good at assessing their own stress levels – their questionnaires corresponded with the levels of stress hormones found in samples.

“What was striking and unexpected,” says Prof. Choukèr, “was the ambiguous immune response we saw in the astronauts’ blood – we saw an over-reaction coupled with severe immune suppression in some areas.”

Small quantities were frozen in space and analysed back on Earth, while more samples of fresh blood taken from the cosmonauts back on Earth were contaminated with common illness-causing pathogens such as fungi, bacteria and herpes.

The researchers found that the immune system reacted heavily to some new threats.

“What would form a mild immune response in blood of a healthy person on Earth seems to cause immune cells in astronauts to go haywire, overreacting to some of the foreign threats.”

The reason is unknown but the implication is that the immune system adapts to the germ-free environment on the Space Station while staying extra alert, possibly due to the unique environmental stress.

Further research is concluding with subjects in similar situations on Earth to rule out the effect of weightlessness. Data are being collected from volunteers in remote research bases in Antarctica and a follow-up study is being prepared that will analyse astronaut blood onsite after being taken in space.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland