Tech for life

From robotics and more efficient batteries to wheel animals with extraordinary survival skills, life and technology are intertwined on the International Space Station. The last deliveries of the year arrived just in time for more science and tests over the Christmas period, aboard two cargo ferries.

Keep it alive

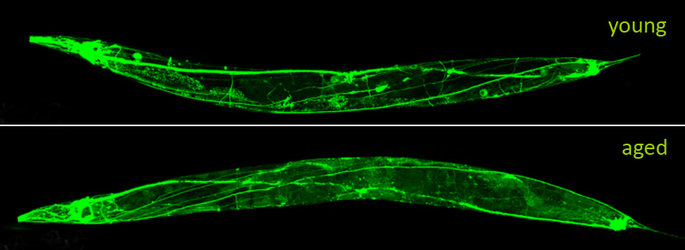

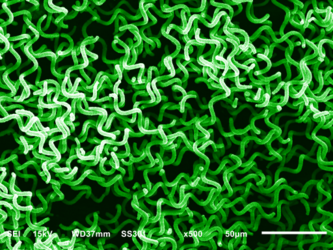

With the spacewalk season on hold until next year, ESA astronaut Luca Parmitano took his time to prepare the orbital home for new, tiny and incredibly resistant passengers. Rotifers, commonly called wheel animals, are usually less than a millimetre in size and usually found in fresh water and moist soil.

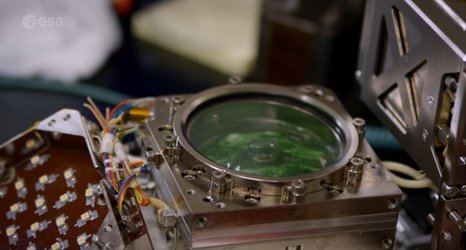

These microorganisms arrived on Sunday on the 19th SpaceX Dragon supply mission, and Luca is hosting them inside Europe’s long running incubator in space, Kubik. The astronaut set the thermostast of their space cubicle at 15°C – the optimal temperature for growing these creatures in.

Biologists are interested to see how these curious animals handle stress and repair damage caused by radiation in microgravity. The results from the Rotifer-B study could lead to improved protection of professionals exposed to radiation in their work or cancer patients during radiation therapy.

Europe’s space laboratory Columbus incubates more new science. Large pharmaceutical companies from Europe and Asia and small startups shipped proteins on the Dragon spacecraft to study their formation without gravity and convective forces that get in the way. Studying protein crystallisation inside the ICE Cubes facility may help scientists design new drugs.

ESA’s latest regenerative life support system received new parts and filters. This European technology capable of recycling carbon dioxide for a cleaner air is expected to be fully operational by early 2020.

The power of knowledge

Batteries developed by this year’s Nobel Prize laureates are helping to power the Space Station. During a live call with laureates in physics and chemistry, NASA astronaut Jessica Meir stated that the new lithium-ion batteries are “a significant improvement in performance and savings: they will last 10 years instead of six years for the older nickel-hydrogen type batteries.”

When Nobel Prize winning chemists invented the lithium ion batteries in the 90s that power everything from our smartphones to electric cars today, ESA was the first one to transfer them to space. Today, Nobel Prize-winning lithium-ion batteries are just as prevalent in space as on Earth, used in everything from the Space Station’s solar arrays to spacesuits, and onboard gadgets.

Access the video

Monday’s science delivery came on the Russian Progress cargo ship. Supplies included new parts for Plasma Kristall-4, an ESA-Roscosmos experiment that helps reveal the dynamics of liquids and solids at the atomic level. Fundamental science helps study how an object melts and how waves spread in fluids.

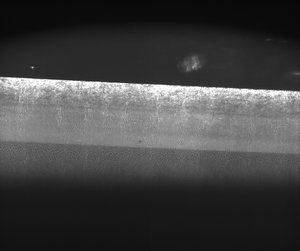

Better heat transfer technology is vital to keep your computer cool, and paradoxically boiling seems to be an extremely efficient way of getting rid of excess heat. The Multiscale Boiling experiment continued to produce large bubbles in space to improve thermal management systems in space as well as in terrestrial applications.

Testing space

The next wave of space exploration will see humans exploring ‘hand-in-hand’ with robots. Luca made robotics history in late November, reaching out from the International Space Station in orbit around Earth at a speed of around 8 km/s, to control a rover in the Netherlands equipped with a highly dexterous robotic arm. He drove the rover to three sites and collected rock samples following the advice of geologists on the ground.

The Analog-1 test project was a success for scientists and robotics teams as Luca proved that ‘force-feedback’ controls allowed high-precision robotic control in weightlessness.

Access the video

Another robotic partnership landed on the Station. CIMON, short for Crew Interactive Mobile CompanioN, is a 3D-printed sphere designed to test human-machine interaction in space.

The second prototype of this artificial intelligence helper will live in the Columbus laboratory for up to three years, displaying information for scientific experiments and repairs and allowing astronauts to keep their hands free to focus on their tasks.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland